Home - Rolf Enlund blog - Index - News - Kronkursförsvaret 1992 - EMU - Cataclysm - Wall Stree

Housing Bubble and Everything Bubble in One Simple Picture

Meanwhile, people keep faith in the Phillips' Curve. It's pathetic

Mish 6 July 2018

There are important implications for investors if central banks are not the main cause of lower interest rates.

For one, it means that rates will probably remain low even after the ECB finishes its asset purchases.

Marc Chandler FT 27 June 2018

My recent book, Political Economy of Tomorrow

When the economy’s human and capital resources are fully utilized (meaning actual GDP is equal to potential GDP), fiscal stimulus just generates inflation and higher interest rates. Even if the extra demand might create some wage pressure, it will be met with higher inflation, so real wages – the paycheck’s actual buying power – won’t change at all.

The problem is that those making that argument are implicitly asserting that they know that the “natural rate of unemployment” – the lowest rate consistent with stable inflation – is roughly equal to the current unemployment rate. That is, they believe we’re at full employment. But the truth is they have no way of knowing that, and one key indicator – inflation – suggests they may be wrong.

Jared Bernstein, chief economist for Vice President Joe Biden, at John Mauldin 18 February 2018

NAIRU: not just bad economics, now also bad politics

Janet Yellen has long believed it’s possible for “too many” Americans to have jobs. In her view,

shared by many of her generation in the economics profession,

consumer prices will rise too fast unless millions of people remain unemployed.

Matthew C Klein, FT Alphaville 24 January 2018

Central banking is hard. But the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco makes it look easy.

Matthew C Klein, FT Alphaville 30/10 2017

They have a game called “Chair the Fed” where you get to set the level of short-term interest rates once every three months.

(The European Central Bank has its own game, which we once wrote about, that was similarly limited but also more fun thanks to the colourful characters.)

Gertjan Vlieghe of the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee put a cogent case that the Phillips curve,

which charts the relationship between unemployment and wage inflation, is far from dead.

John Plender FT 4 April 2018

Years of ultra-low interest rates and low volatility

have dulled sensitivity to the leverage and currency mismatch risks inherent in ever more widespread carry trading.

The exponential growth in derivatives trading means that the embedded leverage in these instruments is an ever greater threat to financial stability.

The Phillips Curve is right at the centre of the most important economic debate of the moment

John Authers FT 16 March 2018

It is now 50 years since Milton Friedman, the great monetarist economist, made a speech to the American Economic Association in which he effectively demolished the Phillips Curve.

By the 1980s, economists, including the Keynesians who had previously endorsed the ideas behind the Phillips Curve, accepted that Friedman was right about this.

Emi Nakamura, a Columbia University economist and one of the foremost academic experts on calculating inflation and deriving Phillips Curve relationships from inflation and unemployment data.

The main points that Emi extracts from a career’s worth of research are that

the Phillips Curve, if it exists at all, is virtually flat.

---

The Costs of Inflation

Exactly how bad is inflation anyway. And does it even matter that much?

John Authers FT 17 March 2018

Riktiga karlar är inte rädda för lite inflation

Englund 19 februari 2010

The Phillips curve may be broken for good

Central bankers insist that the underlying theory remains valid

The Economist 1 November 2017

Since 2010, as the unemployment rate has fallen steadily from 10% to 4.4%, inflation has hovered between 1% and 2%.

This has prompted observers like Larry Summers of Harvard University to argue that the Phillips curve has “broken down”.

The (non) disappearing Phillips Curve: why it matters

The existence, and recent disappearance, of the Phillips Curve is the hottest topic among macro investors and policy makers at the moment.

Gavyn Davies' blog, 22 October 2017

Lawrence Summers, in typically incisive fashion, put his finger on the crux of the matter.

He asked the economic panel to imagine being transported 5 years into the future, and then being asked to assess the debates of 2017.

With the benefit of hindsight, would economists conclude that the Phillips Curve (PC) had been thrown off course for a period, only to re-assert itself later?

Or would they conclude that the whole PC framework had broken down by 2017, and had been replaced by a brand new inflation mechanism. And, if so, what would be the new paradigm?

Why does it matter?

Basically, because it is the bedrock of all the New Keynesian (NK) models that underpin monetary policy in all of the major central banks today.

Remove the PC, and the central bankers are floundering.

The US economy looked eerily similar in late 1965

The US was on the cusp of the Great Inflation.

Wall Street equities lost almost 60pc of their value in real terms over the next decade.

Bondholders were slaughtered.

Ambrose 12 October 2017

Central bankers have one job and they don’t know how to do it

Matthew C Klein, FT Alphaville 18 Octobr 2017

The standard argument is that unemployment and living standards are real things outside the purview of the monetary authority, whereas “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”.

The problem is no one seems to have figured out how central bankers are supposed to influence this “monetary phenomenon” using the tools at their disposal.

Central bankers face a crisis of confidence as models fail

inflation is not behaving in the way economic models predicted

FT 11 October 2017

In short, the new masters of the universe might not understand what makes a modern economy tick and their well-intentioned actions could prove harmful.

The root of the current insecurity around monetary policy is that in advanced economies — from Japan to the US — inflation is not behaving in the way economic models predicted.

Mr Borio says, “the link between measures of domestic slack and inflation has proved rather weak and elusive for at least a couple of decades”.

The relationship between slack and inflation nonetheless appears to hold at global level.

John Plender FT 3 October 2017

All this would undermine elevated asset markets and might trigger worries over debt sustainability.

In a still fragile world economy, the results might be ugly. One might even see a return to the stagflation of the 1970s, with far lower inflation, but also far higher indebtedness.

The starting point is a puzzle: why is inflation so low when the rate of unemployment is already a little below the level the Fed (and most economists) consider to be “full employment”

(the rate at which inflation should start to accelerate upwards).

Martin Wolf FT 10 October 2017

Fed has no reliable theory of inflation, says Former Fed governor Tarullo

FT 4 October 2017

Daniel Tarullo, who left the US central bank’s board of governors earlier this year, said economists displayed a paradoxical faith in the usefulness of unobservable concepts such as the natural rate of unemployment or neutral real rate of interest, even as they expressed doubts about how robust those concepts were.

He was particularly doubtful about the weight inflation expectations play in rate-setting policy, given the “range and depth of unanswered questions” about how they are formed and measured.

“The substantive point is that we do not, at present, have a theory of inflation dynamics that works sufficiently well to be of use for the business of real-time monetary policymaking,” said Mr Tarullo in a speech at the Brookings think-tank in Washington

Bank of England’s Mark Carney argued in his recent IMF Michel Camdessus Central Banking Lecture, globalisation appears to have weakened the relationship between domestic slack and domestic inflation.

The introduction of more and more emerging market workers into the global labour market has clearly exerted a restraining influence on workforces in the tradeable sector of advanced economies.

The relationship between slack and inflation nonetheless appears to hold at global level.

John Plender FT 3 October 2017

If interest rates and bond yields were unjustifiably low, inflation would take off—and puzzlingly it hasn’t.

This suggests that factors beyond the realm of monetary policy have been a bigger cause of low long-term rates.

The Economist 7 October 2017

Perhaps the macro question – is why low unemployment isn’t sparking higher inflation

as the fabled Phillips curve says it should.

John Mauldin, 2 September 2017

A new paper from Philadelphia Fed researchers says the Phillips Curve doesn’t actually help predict inflation.

The authors say their results suggest, instead, that “monetary policymakers should at best be very cautious in their reliance on the Phillips curve when gauging inflationary pressures.”

Now, when I hear Federal Reserve economists say we should “at best be very cautious” about something, I figure they are really saying, “Don’t do that, you idiot.” But of course, they can’t say that directly to the FOMC.

Fortunately, they don’t need to. The committee’s July minutes said that “a few participants” suspected the Phillips framework was “not particularly useful.” How many would “a few” FOMC members be? We don’t know.

Weak wage growth suggests the /US/ economy is not at full employment

Death of the Phillips curve? Nonsens.

If the economy takes off above Stall Speed the Philips Curve will be back.

Englund blog 2017-09-02

Atlanta Fed's gauge of "sticky-price" inflation in the US

soared to a post-Lehman peak of 3 pc

Ambrose 2016-03-16

The Return of the Original Phillips curve?

Why Lars E O Svensson’s Critiq ue of the Riksbank’s Inflation Targeting is Misleading

Fredrik Andersson and Lars Jonung, June 2015

Download it here

Lars E O Svensson:

En lägre ränta hade lett till lägre skuldkvot, inte högre.

Det beror på att en lägre ränta ökar nämnaren (nominell disponibel inkomst) snabbare än täljaren (nominella skulder).

Why the Fed Buried Monetarism

Friedman’s “natural” rate was replaced with the less value-laden and more erudite-sounding “non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment” (NAIRU).

Central bankers now seem to be implicitly (and perhaps even unconsciously) returning to pre-monetarist views:

tradeoffs between inflation and unemployment are real and can last for many years.

Anatole Kaletsky; Project Syndicate, 22 September 2015

If monetary policy is used to try to push unemployment below some pre-determined level, inflation will accelerate without limit and destroy jobs. A monetary policy aiming for sub-NAIRU unemployment must therefore be avoided at all costs.

A more extreme version of the theory asserts that there is no lasting tradeoff between inflation and unemployment.

Despite empirical refutation, the ideological attractiveness of monetarism, supported by the supposed authority of “rational” expectations, proved overwhelming.

As a result, the purely inflation-oriented approach to monetary policy gained total dominance in both central banking and academic economics.

Capitalism 4.0 by Anatole Kaletsky, Rolf Englund 20/10 2010

Trots löften om full sysselsättning har regeringen och Socialdemokraterna accepterat en omdiskuterad modell där arbetslösheten inte får sjunka under en viss nivå. Ty då stiger inflationen.

Enligt Konjunkturinstitutet och Riksbankschefen ligger den arbetslöshetsnivån i dag på närmare sju procent.

Det visar en granskning som SVT:s Uppdrag granskning gjort.

Dokument som SVT läst visar att regeringens ekonomiska politik till stor del utgår från en 40 år gammal teori som kallas jämviktsarbetslöshet.

SVT Text Onsdag 10 sep 2014

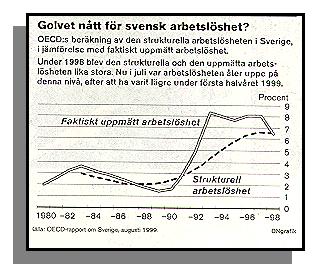

Kommentar RE:

Skillnaden mellan den faktiska och den strukturella

arbetslösheten

(i diagrammet framräknad, på något sätt, av Konjunkturinstitutet)

är definitionsmässigt = den konjunkturella

arbetslösheten, som beror på riksbankens och regeringens kombinerade inkompetens.

Mer om kronkursförsvaret och bank- och finanskrisen runt 1992

The Case For Higher Inflation

Olivier Blanchard, currently the chief economist at the IMF,

conclusion, central banks have been setting their inflation targets too low

I’m not that surprised that Olivier should think that; I am, however, somewhat surprised that the IMF is letting him say that under its auspices. In any case, I very much agree.

Paul Krugman, Febr 13 2010

Inflationen tenderar att driva på sig själv.

När löntagare, företag och andra aktörer i ekonomin ställer in sig på högre priser så vill de kompensera sig,

vilket leder till ytterligare prishöjningar.

Per T Ohlsson, 8 juni 2008

Det var bland annat sådana inflationsförväntningar som på 1970- och 1980-talet fick den svenska inflationen att emellanåt överstiga 10 procent.

Alla prishöjningar är inte inflation. Vissa varor kan t ex bli dyrare därför att de är svåra att få tag på. Det kallas relativprisförändringar.

Vintern 1991 uppgick den svenska inflationen till 13 procent. Tre år senare var den nere på 2 procent. Under samma period exploderade arbetslösheten. Först efter detta ”stålbad” kunde svensk ekonomi växla in på sin mest gynnsamma bana sedan rekordåren på 1960-talet: hög tillväxt, ökande sysselsättning, starka statsfinanser – och låg inflation.

Men särskilt på vänsterhåll finns en kvardröjande föreställning om att en politik som prioriterar låg inflation innebär högre arbetslöshet.

Och omvänt: bara man accepterar högre inflation så kan arbetslösheten pressas ned.

Who gives a damn about inflation?

Now that the age of moderation has ended, we are returning to Phillips curve-type discussion.

rising inflation is the most painless way out of a debt crisis

Wolfgang Münchau blog 31.01.2008

Seminal research showed how central banks can be tempted to exploit the short-run Phillips curve tradeoff

by permitting a higher rate of inflation today in order to push down unemployment temporarily.

But such behaviour has the consequence of generating higher, self-fulfilling inflation expectations in the future.

Robert Barro and David Gordon (1983), "A Positive Theory of Monetary Policy in a Natural Rate Model,"

Journal of Political Economy, vol. 91, pp. 589-610.

Paul McCulley and Ramin Toloui November 2007

Jämviktsarbetslösheten var högre vid mitten av 1990-talet än vid början av 1980-talet.

Den är nu sex procent.

Anders Forslund, Finanspolitiska Rådet maj 2008

If haircuts and dress styles can come back into fashion, then so can economic theories.

That is why policymakers have recently been debating the implications of the shape of that very 1960s concept, the Phillips curve.

New Economist September 29, 2006

Well-anchored inflationary expectations are not – repeat not – the end all and be all of life.

Accordingly, they should not be the end all and be all of monetary policy, despite the huge volume of written and oral rhetoric offered by a chorus of policy makers to that effect.

Paul McCulley, Pimco July 2007

Milton Friedman introducerade begreppet den "naturliga" arbetslösheten, vilket kunde uppfattas som stötande.

Men hans slutsatser är numera allmänt accepterade: det lönar sig inte att låta priserna stiga för att kortsiktigt driva ner arbetslösheten, eftersom effekterna inte är varaktiga.

Kostnaden blir alltför hög när inflationen måste ner igen, ofta genom hård budgetåtstramning och skyhöga räntor.

Johan Schück, DN 21/11 2006

Kommentar av Rolf Englund:

Men om arbetslösheten ligger över NAIRU, då kan det väl inte vara fel att

stimulera efterfrågan för att få upp sysselsättningen?

Att man inte gör det får skyllas på den stupida Stabilitetspakten inom EMU.

Differences between the Natural Rate of Unemployment and the NAIRU

Wikipedia

Okun's law

can be stated as saying that for every one percentage point by which the actual unemployment rate exceeds the "natural" rate of unemployment, real gross domestic product is reduced by 2% to 3%.

Wikipedia

The Keynesians' belief that government policy could wisely make trade-offs between rates of inflation and rates of unemployment was epitomized in the Phillips Curve, which seemed to lend empirical support to that belief. Friedman dealt that analysis a body blow when he argued that it was not the rate of inflation which reduced unemployment but the fact that inflation exceeded expectations. In other words, even a high rate of inflation would not reduce unemployment if inflationary policies became so common as to be expected.

The "stagflation" of the 1970s - with simultaneous double-digit inflation and double-digit unemployment - validated what Friedman had said, in a way that no one could ignore.

Thomas Sowell, WSJ November 18, 2006

Almost a new economic miracle

Germany has been one of the very few countries apart from Japan to experience an

actual fall in unit labour costs in manufacturing.

Samuel Brittan, FT April 13 2007

Flattening of the Phillips Curve:

Implications for Monetary Policy

IMF/Iakova, Dora M., April 1, 2007

The focus is on the implications of a globalization-related flattening of the Phillips curve for the trade-off between inflation and output gap variability and for the efficient monetary policy response rule.

Factor-price equalization - Faktorprisutjämning

"Friedman is dead, monetarism is dead, but what about inflation?"

Macroblog

Now, unfortunately, there are reasons to think that the US economy’s potential growth rate has fallen as low as 2.5 per cent.

Stephen Cecchetti, FT 12/12 2006

The writer is Rosenberg professor of global finance at the Brandeis International Business School

This “speed limit” depends on three things: growth in the labour force, capital investment and technological progress. Half the story is demographics and the other half is investment.

Returning to the Fed’s current challenge, regardless of how it is measured inflation is running about 1 percentage point above what policymakers refer to as their “comfort zone”. If potential growth has fallen, then the recent slowing is not just part of a normal cycle, and there is virtually no slack in the economy. Without that slack, inflation will not come down unless interest rates rise further.

So why hasn’t the unemployment rate already risen?

The short answer to the puzzle is that the labor force participation rate has fallen,

accounting fully for the drop from 4.7% to 4.5% for the unemployment rate over the last year.

Paul McCulley, May 2007

Prudent monetary policy must maximize a real-time utility function for society, otherwise known as cyclically fine tuning aggregate demand to aggregate supply potential, so as to minimize cyclical volatility in both unemployment and inflation. Or, if you prefer, prudent monetary policy must exploit and optimize the real-time trade-off between employment and inflation.

Yes, for you economist readers, I know that there is no long-term trade off, that there is no long-term Phillips Curve (3.Paul McCulley, April 2007)

Well actually, I don’t know that, but will accept it as the gospel of our profession, because whether a long-term Phillips Curve exists or doesn’t exist doesn’t really matter for investment horizons that are relevant to what PIMCO does.

The fact of the matter – both commonsensical and empirical – is that a cyclical Phillips Curve does exist, both because of price rigidities and frictions in the economy, and because as Alan Greenspan famously notes, human nature will never be repealed, and humans are inherently moody, both individually and collectively.

Which is the proximate reason that asset markets are inherently given to cycles of boom and bust: human nature is inherently given to momentum investing, not value investing.

So why hasn’t the unemployment rate already risen? It is a historical fact that nonfarm payrolls – before annual benchmark revisions, which continue for six years! – understate employment early in recoveries (leading to the inevitable contemporaneous label of "jobless recovery"), while they overstate employment late in expansions.

Over the long-run, the “neutral” stance of monetary policy (also known as the equilibrium real federal funds rate) should be closely related to the potential growth rate of GDP.

Chart 2 shows that the historical “spread” between the real federal funds rate and real GDP growth has been systematically mean reverting.

Paul McCulley and Saumil Parikh, November 2006

The American economy shrank so much between 1929 and 1933, they /Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz/ argued, not because Wall Street crashed, because governments put up trade barriers or because under capitalism slumps are inevitable.

No: trouble was turned into catastrophe by the Federal Reserve, which botched monetary policy, tightening when it should have loosened, thus depriving banks of liquidity when it should have been pumping money in.

Hence Mr Friedman's mistrust of independent central banks. He thought they should limit inflation by targeting the rate of growth of the money supply. Aiming for inflation directly, he thought, was a mistake, because central banks could control money more easily than prices.

Brilliant as his monetary diagnoses were, on the details of the remedy he came out on the wrong side. Controlling the money supply proved far harder in practice than in theory (notably in Britain in the 1980s: Mr Friedman grumbled that the British authorities were going about it in the wrong way).

If Mr Friedman had a favourite economy, it was Hong Kong. Its astonishing economic success convinced him that although economic freedom was necessary for political freedom, the converse was not true: political liberty, though desirable, was not needed for economies to be free. Why, he asked, had Hong Kong thrived when Britain, which controlled it until 1997, was so statist by comparison? He greatly admired Sir John Cowperthwaite, the colony's financial secretary in the 1960s, “a Scotsman...a disciple of Adam Smith, his ancient countryman”.

http://www.economist.com/opinion/displaystory.cfm?story_id=8313925

The U.S. economy has slowed to a level below its trend growth rate during the second half of 2006.

Trend growth, the rate that can be sustained over time without rising inflation, is probably about 3 percent,

having been reduced by a quarter of a percentage point by weaker productivity data.

John H. Makin October 23, 2006

America's underlying inflation rate is already uncomfortably high. For inflation to fall, the economy needs to grow below its trend rate, but if that rate is dropping, the Federal Reserve's task becomes harder: raise interest rates too far and recession looms; do too little and inflation worsens.

The failure of central bankers to recognise that the economic speed limit had dropped was one reason why inflation spun out of control in the 1970s. (RE: See Stagflation)

The Economist editorial 26/10 2006

“Natural” does not mean optimal.

Nor, Mr Phelps has written, does it mean “a pristine element of nature not susceptible to intervention by man.” Natural simply means impervious to central bankers' efforts to change it, however much money they print.

The Economist 12/10 2006

Källa: Artikel av Johan Schück i DN 99-08-21

Den strukturella arbetslösheten är = NAIRU.

Varför

skulle den ha ökat från nivån 2-3 procent i slutet av

1980-talet till nivån 6-7 procent nu?

We discussed in Jackson Hole:

Phillips Curves in the industrial world, particularly the United States, have become much flatter as the result of globalization.

That is, the trade-off between unemployment and inflation in the United States has become weaker, because labor costs embedded in the products and services we consume in America are a function of not just US wages, but global wages, which are a function of both expansion and slack (unemployment) in the global labor market.

Paul McCulley, PIMCO September 2006

Ekonomipriset till Edmund Phelps

Visst beror dagens problem i ekonomin i någon mån på missgrepp i slutet av 80-talet och början av 90-talet.

Men ...Mats Svegfors 94-09-10

Proposed by American economist Milton Friedman (1912-1992), NAIRU refers to the long-term rate of unemployment at which inflation neither rises nor falls, as upward and downward pressures on wage and price inflation are in equilibrium.

The vertical Phillips curve illustrates this situation.

economyprofessor.com

Can the US Economy Grow Above 2.5% and Unemployment Fall Below 5%

Without Causing an Increase in Inflation ?

Roubini

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

NAIRU: Is It Useful for Monetary Policy?

Nationalekonomen Per Lundborg hävdar att om inflationsmålet höjs

skulle en finanspolitisk expansion relativt snabbt få ner arbetslösheten till 2-2,5 procent.

Det finns ingen strukturell förändring på arbetsmarknaden som skulle utgöra ett hinder.

Sänkta bidrag är obehövliga.

Danne Nordling blog 16/5 2006

Full text

"Inflationsmålen är satta i tron att det inte finns något långsiktigt samband mellan inflation och arbetslöshet,

men mycket tyder på att det gör det. Höjer vi inflationsmålet till 4 procent kan det kraftigt minska arbetslösheten

och den högre inflationen medför i sig inga kostnader", säger Per Lundborg.

DI 2002-05-30

Göran Persson: Människors uppoffringar har givit resultat

i regeringsförklaringen i Riksdagen, Tisdagen den 14 september 1999

Klas Eklund

Den svaga arbetsmarknaden motiverar expansiv finanspolitik, menar SEB:s ekonomer. Det strider mot varningarna nyligen från tre professorer. Men trots underfinansiering blir det bara 30 000 nya jobb 2007.

I dagens media (31/8) rapporterar man om SEB:s konjunkturprognos med uttalanden av chefekonomen Klas Eklund.

Huvudbudskapet är att det går hyfsat bra för Sverige. De varningar för expansiv finanspolitik när ekonomin växer som uttalats av Hamilton, Jonung och Ingemar Hansson får inget stöd av Eklund.

Han säger i SvD 31/8: - Det är svårt att kalla det för en procyklisk politik när arbetsmarknaden är svag. Jag har svårt att hetsa upp mig för det här.

Danne Nordling 31/8 2005

Arbetslivsministern: Jämviktsarbetslösheten i svensk ekonomi ligger i dag ordentligt under 4 procent"

När Riksbanken lanserade låginflationspolitiken 1995 behövdes en högre ränta

DI 3/3 2005

När Riksbanken lanserade låginflationspolitiken 1995 behövdes en högre ränta för att få fason på lönebildningen, hävdar Hans Karlsson med ett förflutet som LO:s avtalssekreterare. "Det var tufft, men rätt då. Problemet är att Riksbanken fortfarande har en uppfostranspremie i räntesättningen."

Arbetslivsministern sågar även centralbankens farhågor för att inflationen ska sticka iväg om arbetslösheten kryper under 4 procent. "Alldeles fel. Jämviktsarbetslösheten i svensk ekonomi ligger i dag ordentligt under 4 procent", säger han, men vill inte ange någon siffra.

P-O Edin: Skillnaden mellan dagens arbetslöshet och den arbetslöshet som är förenlig med stabila priser (Nairu)... är 1,5-2 procent, vilket skulle motsvara 60 000-70 000 jobb. DN 16/10 2004

Någonting har hänt, men vad?

Industrilönerna är nu lägre än i konkurrentländerna och överskottet i bytesbalansen stiger år för år, men investeringarna har sedan länge stagnerat. Pengarna satsas utomlands, inte här.

DN-ledare 30/9 2004

Oväntat stöd för Riksbankens linje kom i går

från LO-ekonomen Dan

Andersson. Svensk ekonomi klarar inte en öppen arbetslöshet

på fyra procent utan att inflationen tar fart.

SvD-ledare

2002-04-19

Den senaste tiden har det blivit uppenbart att

ekonomerna nu tvingas tänka om.

Dagens Industri 2000-09-18,

Anders Jonsson

Den senaste tiden har det blivit uppenbart att ekonomerna

nu tvingas tänka om. Det handlar om det som brukar kallas

jämviktsarbetslösheten eller med en ekonomförkortning, NAIRU.

Det vill säga den punkt där arbetslösheten inte kan minska mer

utan att inflationen tar fart.

"The NAIRU in Theory and Practice," by N. Gregory Mankiw (with Laurence Ball) (pdf)

Milton Friedman explains what Nairu is

The Economist on NAIRU, april 1999

Wall Street Journal on NAIRU, april 1999

Irwin Kellner: Throw out that NAIRU (april 1999)

Samuel Brittan on NAIRU and the prices on Wall Street, May 1999

Martin Wolf on NAIRU, May, 1999

Wall Street Journal, June 29, 1999, The Greenspan Rule

Englund about New Era, June 29, 1999

Johan

Schück i DN om Nairu och Ulf Jakobsson

Om jag får Nobelpriset i ekonomi, vilket förefaller

osannolikt, är det nog för detta:

Lägesenergikoeffecienten? Rolf Englund i

Nyhetsbrevet Credit nr 14

(augusti) 1989 aktuellt i samband med konvergenskriterierna

Det är vanligt att ekonomer jämför olika länders läge på Philipskurvan. Om ett land A (t ex England) har en inflation på 4 procent och en arbetslöshet på 6 procent och annat land, land B (t ex Västtyskland) har detsamma, så ligger det nära till hands att anta att ländernas ekonomier står inför samma framtidsutsikter.......

Time-varying Nairu and real interest rates in the Euro Area

Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (DIW

Berlin) 2003

Låg

inflation och låg arbetslöshet möjlig

Bo Lundgren i

Veckobrev 30 maj 2002

Högre inflationsmål får stöd

DI 2002-05-30

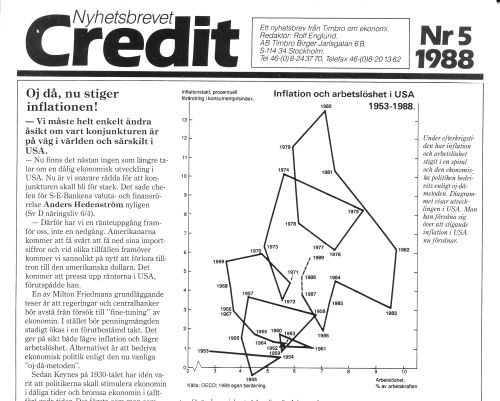

SvD-ledare 2000-02-02:

Ofta påstås att vi måste välja mellan att ha antingen hög arbetslöshet eller hög infla tion. Så behöver det inte alls vara. Allt beror på vilka förutsättningar som gäller.

Det är fullt möjligt att uppnå både låg in flation och låg arbetslöshet, som i USA un der 1950-talet, då inflationen låg på ett par procent om året och arbetslösheten uppgick till tre - fyra procent. Det går också att ha bå de hög arbetslöshet och hög inflation samti digt, så kallad stagfiation, vilket 70-talets kriser i västvärlden visade.

USA har i dag återvänt till något som lik nar 60-talets förhållande mellan inflation och arbetslöshet. Framgångarna grundas bland annat på en kombination av inflations bekämpning, låga skatter och stor rörlighet på arbetsmarknaden. Samma politik skulle fungera i Sverige.

FT-leader, May 18, 1999

The US Federal Reserve is going to have to raise interest rates soon. Today, at least it should signal a shift in its monetary policy stance to a bias towards tightening.

The Fed's cumulative 0.75 per cent interest rate cuts last autumn helped restore calm to international financial markets. Strong US growth since then - 6 per cent on an annualised basis in the last three months of 1998 and a 4.5 per cent rate at the start of this year - has supported world demand.

Indeed, as the outlook in Europe and Japan has worsened, it is stronger-than-expected US growth together with the beginnings of a recovery in developing Asia that have improved the global outlook.

A rise in US interest rates will not help economies that are still struggling. But there are risks to the world from the US overheating.

The Fed's international responsibilities have justified its decision to allow domestic demand to continue to race ahead. But this is a gamble: the 7 per cent annualised rate in the first three months of the year is clearly unsustainable.

The danger, if it waits too long, is that the Fed will have to raise rates sharply. This might be because an exploding current account deficit triggers a fall in the dollar. It might be because the combination of lucky breaks and productivity growth subduing inflation is reversed.

Perhaps the latter is already happening. Consumer price inflation rose at a month-on-month rate of 0.7 per cent in April, the biggest increase for nine years. The core rate, stripping out the rise in oil prices, was 0.4 per cent, the highest for four years.

Of course, this was only one month's data. It may be a blip rather than the start of a trend: wage pressures and producer price increases have remained subdued.

However, the GDP deflator - a broader measure of inflation - has also jumped from the last quarter of 1998 to the first quarter of 1999.

Even if inflationary pressures are building, domestic demand may slow of its own accord. A levelling off of the stock market would reverse the wealth effect that has been driving consumer demand, leading households to start saving again. Rapid investment growth may cool.

But the Fed's repeated forecasts of a slowing economy - just like everyone else's - have so far been wrong. It should raise interest rates, reversing last autumn's emergency cuts. If it does not do so today, the FOMC must certainly signal, unequivocally, that it will start taking back the cuts soon.

This might unsettle equity markets (bond markets have already priced in higher short-term interest rates). But if equity investors are caught napping, that is too bad. The Fed should show that it will not be caught asleep on the job.

TREASURY SECRETARY ROBERT E. RUBIN

STATEMENT TO THE

IMF INTERIM COMMITTEE

April 27, 1999.

The United States has borne the bulk of the burden of global current account adjustment in response to the Asia crisis and subsequent emerging market turmoil in 1996-1998. Japan's current account surplus has increased over this period, while Europe's has remained relatively stable. This situation cannot continue indefinitely. Japan and Europe must boost domestic demand-led growth.

In Europe, we have witnessed in recent months the advent of the new common currency, the euro. The United States continues to believe that a successful euro that brings a new dynamism to the European economy is very much in the world's interest. Yet the prospect for such a result in the long-term is not enough. Expectations for medium-term growth in Europe have deteriorated in recent months.

It is important that Europe redouble its efforts to increase domestic demand and make a significant contribution to recovery worldwide. Structural reforms will be particularly important in providing the right set of incentives for investment and job creation.

http://www.ustreas.gov/press/releases/pr4009.htm

Inflation can be too low

By Samuel Brittan

Financial Times, June 5 2002 20:42

The last International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook contained a section entitled "Can inflation be too low?". The suggested answer was "Yes". Coming from an organisation regularly attacked as a pillar of western capitalist orthodoxy, the conclusion is pretty remarkable. It is also highly topical when so many central banks are pondering when to raise interest rates.

A serious difficulty about zero inflation is that it puts a floor under how far the real rate of interest - that is, the rate corrected for inflation - can fall. In the recessio n of the mid-1970s, triggered by the first oil price explosion, the world experienced double-digit inflation; and in many countries the real rate of interest was negative. This could well be one reason why the world did not experience more than a pause in the upward movement of output.

If, however, inflation is absent, nominal interest rates cannot fall below zero, where they have more or less been in Japan for several years. Moreover, most personal and many corporate borrowers have to pay a couple of percentage points above official interest rates. So if a near-zero base rate or prime rate is not enough to boost consumption or stimulate investment sufficiently in a recession, the economy will not easily recover.

That is why the IMF warns that "deflation blunts the effectiveness of monetary policy . . . There is a danger that with real interest rates prevented from falling, output recovers only slowly and deflation gathers force ... If the shocks hitting the economy are large enough, this dynamic interaction can lead to a downward spiral that cannot be tackled by short-term interest rate policy alone."

This situation resembles what John Maynard Keynes called a liquidity trap, although the mechanics are somewhat different.

Högre inflationsmål får

stöd

DI 2002-05-30

Om Sverige går med i EMU bör vi verka för att Europeiska centralbankens inflationsmål höjs. Det anser företrädare för flera riksdagspartier. Riksbankens mål bör dock ligga fast, anser de flesta av dem.

I onsdagens DI hävdar ett antal ledande svenska ekonomer att den Europeiska centralbankens (ECBs) mål att hålla inflationen mellan 0 och 2 procent är alltför lågt och att det kan medföra högre arbetslöshet om Sverige går med i EMU.

Och ekonomernas slutsatser får stöd av företrädare för flera politiska partier. De tycker att Sverige, vid ett EMU-medlemskap, bör verka för att ECBs inflationsmål höjs.

"Ett alltför lågt mål är ju inte bra. Sverige har ett mycket tydligare mål. Det borde ECB också ha. I praktiken skulle det innebära en höjning till 2 procent, plus-minus någon procentenhet", säger folkpartiets ekonomiska taleskvinna Karin Pilsäter.

Och hon för stöd av kollegan i centerpartiet Lena Ek. "ECBs inflationsmål tycker jag är för lågt. Om vi går med i EMU tycker jag att det svenska inflationsmålet vore värt att argumentera för."

Även moderaternas partiledare Bo Lundgren tycker att 2 procent kunde vara ett lämpligt mål för ECB. Samtidigt säger han sig vara "förskräckt" över tanken att vi borde tillåta högre inflation som ett sätt att hålla nere arbetslösheten, som några av ekonomerna argumenterar för i DI.

- "Att vi hamnat i ett läge där vi kanske inte klarar låg inflation och låg arbetslöshet samtidigt visar på misslyckandet för regeringen Perssons ekonomiska politik", säger Bo Lundgren.

Mer av Bo Lundgrens odödliga tankar i urval

Kristdemokraternas Mats Odell tror att det blir svårt att ändra ECBs mål. "Det är ett projekt som vi inte råder över. Jag utesluter inte att det kommer att bli aktiviteter åt det hållet, men jag tycker inte det är någon prioriterad uppgift för Sverige", säger han.

Inget av de fyra borgerliga partierna ser dock någon anledning att ändra Riksbankens inflationsmål, som några av ekonomerna förespråkar.

Det tycker däremot Johan Lönnroth, vice partiledare för vänsterpartiet. "Det vore rimligt om såväl ECB som Riksbanken siktade på en inflation på 3 eller 4 procent. Om vi, Gud förbjude, går med i EMU är det dock det viktigaste att vi arbetar för att sysselsättningen blir det överordnade målet för ECB och den övriga ekonomiska politiken", säger han.

En annan vänsterman, LOs chefsekonom Dan Andersson, håller inte med. "Inte minst lönebildningen måste bli effektivare innan det kan bli aktuellt att riva upp inflationsmålet. Däremot är jag kritisk till hur Riksbanken tillämpar målet", säger Andersson.

När det gäller ECB tycker han det vore rimligt med ett punktmål på 2 procent.

Europeiska centralbanken bör tilllåta högre inflation så att arbetslösheten hålls ned. Det tycker ledande svenska ekonomer i en paneldiskussion som DI bjudit in till.Även Riksbanken borde se över sitt inflationsmål, anser flera i panelen.

Efter ett år med inflationstal som legat över Riksbankens mål på 2 procent (± 1 procentenhet) har den klassiska tvistefrågan om sambandet mellan inflation och arbetslöshet åter hamnat i centrum för den ekonomiska debatten.

Riksbankschefen Urban Bäckström konstaterade nyligen att arbetslösheten (3,8 procent i den senaste SCB-mätningen) kanske är lägre än den svenska ekonomin tål om inflationsmålet ska kunna hållas.

Andra bedömare, däribland ekonomer hos den västliga samarbetsorganisationen OECD och Handelsbanken, varnar för att arbetslösheten måste stiga över 5 procent om inflationsmålet ska kunna nås.

Lars Calmfors är inne på liknade tankegångar. "Det finns en del som talar för att vi har kommit ned i en arbetslöshet som ligger något i underkant. Vi ser tendenser till stigande löneökningstakt, och det finns spänningar när det gäller att ändra lönerelationerna mellan olika sektorer i ekonomin", säger han.

DIs övriga paneldeltagare är mer optimistiska. Konjunkturinstitutets bedömning är att arbetslösheten i dagsläget ligger strax ovanför den nivå där inflationen riskerar att ta fart.

Trots att arbetslösheten i dag ligger 1 procentenhet lägre

än på toppen av högkonjunkturen 2000, är

samhällsekonomin som helhet mindre ansträngd nu än då,

anser Tomas Pousette. Nu är det betydligt lättare att rekrytera

personal i tidigare ansträngda sektorer, och löneökningstakten

är på väg ned, konstaterar han.

"I dag är det

lättare att få tag på en kvalificerad datatekniker än en

chaufför. Men det är lätt att få tag på

chaufförer också", säger Tomas Pousette.

De flesta i DI-panelen tror fortfarande att Riksbankens inflationsmål går att kombinera med regeringens arbetslöshetsmål på 4 procent.

Lars Calmfors är dock skeptisk. "Det är möjligt att

målen är förenliga, men jag skulle inte basera politiken

på en sådan förmodan. Risken för att det hela inte ska

fungera är alltför stor", säger han.

Han

förespråkar så kallade strukturreformer, i syfte att göra

det mer attraktivt att vara på arbetsmarknaden än att stå

utanför. Höjningen av nivåerna i a-kassan från den 1 juli

är ett steg i fel riktning, enligt Lars Calmfors.

Att den har kunnat pressas ned betydligt sedan dess beror i hög grad på att lönebildningen har förbättrats; att fack och arbetsgivare har insett att återhållsamhet betalar sig, anser Lars Calmfors. Men nu ser han risker för att utvecklingen börjar gå i motsatt riktning. "Lönedisciplinen urholkas i takt med att minnet av 1990-talskrisen förbleknar. Och går vi med i EMU, har vi ingen centralbank som reagerar på löneökningstakten i Sverige. Den avskräckande effekten försvinner", säger han.

Flera i panelen anser att dagens inflationsmål är lite väl snävt.

"Inflationsmålen är satta i tron att det inte finns något långsiktigt samband mellan inflation och arbetslöshet, men mycket tyder på att det gör det. Höjer vi inflationsmålet till 4 procent kan det kraftigt minska arbetslösheten och den högre inflationen medför i sig inga kostnader", säger Per Lundborg.

Tillsammans med kollegan Hans Sacklén varnar han i en färsk uppsats för att den svenska arbetslösheten kommer att pressas upp mot 6 procent om Sverige går med i EMU, eftersom ECB har ett strängare inflationsmål (0-2 procent).

Meningarna i panelen går isär när det gäller huruvida ett EMU-medlemskap skulle medföra en kraftig ökning av arbetslösheten, men det råder enighet om att ECBs inflationsmål är alltför strängt.

"ECBs nuvarande inflationsmål är förmodligen farligt lågt. Jag tror att man kommer att justera upp det, och det vore klokt. Först och främst eftersom de aldrig kommer att klara det", säger Lars Calmfors.

Ingemar Hansson: "Framför allt är det är beklagligt att ECB inte har ett tydligt mål. Frågan är om skillnaderna mellan Riksbanken och ECB verkligen är så stora, men ett EMU-medlemskap kan naturligtvis innebära spänningar och svårigheter att hålla ned arbetslösheten. Särskilt om löneökningstakten i Sverige fortsätter att ligga över EMU-snittet", säger han."2-2,5 procent vore ett lämpligt mål för såväl Riksbanken som ECB. Det är samma nivå som i bland annat Storbritannien och Norge", fortsätter Ingemar Hansson.

Per Lundborg förespråkar större höjningar av inflationsmålen. Alla är dock överens om att Sverige inte ensidigt kan höja inflationsmålet. Det skulle skapa stor oro på finansmarknaderna.

"Innan Sverige beslutat sig om vi ska gå med i EMU är det otänkbart. Först om vi beslutar oss för att stå utanför under lång tid kan det bli aktuellt att diskutera en ändring av Riksbankens inflationsmål", säger Ingemar Hansson.

Tomas Pousette, analytiker på Nordea: I bästa fall är inflations- och arbetslöshetsmålet förenliga. Men jag tror att vi ligger ganska nära någon sorts gräns där det kan uppstå problem."

Lars Calmfors, professor i nationalekonomi vid Stockholms universitet, före detta EMU-utredare: "Ett inflationsmål på 2,5 procent kanske hade varit bättre för Riksbanken, men förändringar bör undvikas."

Hans Sacklén, doktor i nationalekonomi på Fief, fackföreningsrörelsens institut för ekonomisk forskning: "En inflation på 4 procent skulle ge lägsta möjliga arbetslöshet."

Per Lundborg, professor i nationalekonomi på Fief: "Det är svårt att se hur det ska gå till att skapa stabilitet beträffande arbetslösheten i EMU. Det enda sättet vore att sätta inflationsmålet väldigt högt."

Den svenska Bank- och Finanskrisen