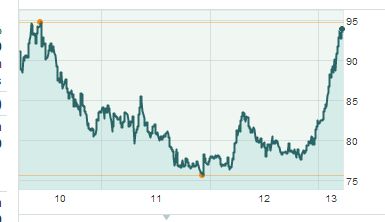

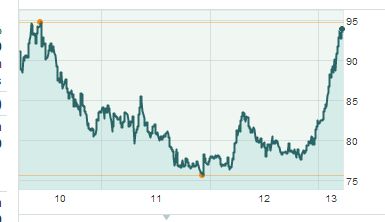

Yen per Dollar 2011-2013

Home - News - Kronkursförsvaret 1992 - EMU - Cataclysm -

Wall Street Bubbles - Huspriser

Dollarn - Finanskrisen - Löntagarfonder

- Contact

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur officially accepted Japan's surrender on 2 September 1945,

aboard USS Missouri anchored in Tokyo Bay, and oversaw the occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1951.

As the effective ruler of Japan, he oversaw sweeping economic, political and social changes.

Wikipedia

American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur, Amazon

Mr Edwards’ “Ice Age” thesis

first honed in the late 1990s that markets in the West were about to follow the example set by Japan

suffering violent deflation, bond yields heading to zero and a collapse in equity values

after the Japanese bubble burst at the end of the 1980s.

FT 9 June 2018

The worst property crash in modern times occurred in and around Tokyo in the late Eighties.

A frenzy of demand within the city’s limited physical terrain saw residential land prices rise 45pc between 1985 and 1986,

and then, incredibly, more than double again in the next 12 months.

In three, blazing years, the price of a square metre of Tokyo residential land rose 299 pc.

Richard Dyson, 9 March 2014

It was fuelled by credit provided by banks which in turn borrowed against their own growing stock market valuations,

all of which led to the apocalyptic crash of the early Nineties.

By then some unfortunate home owners – not only wealthy people – found they were saddled with mortgages 80pc greater than the value of their flats.

Financial Crisis in USA - Financial Crisis in Asia - Financial Crisis in Sweden

See also: The Next Bubble - House prices

Richard Duncan is a financial analyst based in Asia and author of "The Dollar Crisis: Causes, Consequences, Cures" (John Wiley & Sons, 2003), now available in a "Revised & Updated" paperback edition with 7 new chapters.

After predicting in his 2003 book "The Dollar Crisis" that the U.S. property bubble would trigger a global recession,

Duncan's new book argues that governments will have to keep stimulating their economies because U.S. demand for cheap goods will not return to the halcyon days of the 2003 to 2007 boom.

CNBC december 2009

zc

Japan is the catalyst that could bring the record-setting bull market for stocks across the globe to a screeching halt,

according to Société Générale’s uberbear Albert Edwards, Market Watch 10 January 2018

How Japan resists the populist tide

John Plender, FT 1 January 2017

The starting point might be the extraordinary hierarchical, consensual and inclusive nature of Japanese society.

Japan

Which major economy is most likely to disappoint expectations this year,

and perhaps even cause a financial crisis big enough to break the momentum of global economic recovery?

Anatole Kaletsky, 14 March 2014

While Japan no longer attracts much attention these days, it is still the world’s third-largest economy,

with a gross domestic product equal to France, Italy, Spain, and Portugal combined.

As you may have seen, Japan’s public debt has hit one trillion quadrillion yen.

That is roughly $10 trillion. It will reach 247pc of GDP this year (IMF data).

No problem. Where there is a will, there is a solution to almost everything.

Let the Bank of Japan buy a nice fat chunk of this debt, heap the certificates in a pile on Nichigin Dori St in Tokyo, and set fire to it.

That part of the debt will simply disappear.

You could do it as an electronic accounting adjustment in ten seconds.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, August 9th, 2013

Or if you want preserve appearances, you could switch the debt into zero-coupon bonds with a maturity of eternity, and leave them in a drawer for Martians to discover when Mankind is long gone.

Last night's panic in Tokyo, where the Nikkei dropped a stomach churning 7 per cent, demonstrates just how difficult it's going to be for the world's central banks to exit their loose money policies.

You can do what Britain, and now Japan, are attempting, and inflate your way out of it.

Central bankers dream of getting back to "normal" – normal interest rates, a normal balance sheet, and so on.

But that point isn't going to come any time soon.

Jeremy Warner, Telegraph 23 May 2013

The new governor of the Bank of Japan, Haruhiko Kuroda,

not wedded to central bankers’ obsolete doctrines, he has made a commitment to reverse Japan’s chronic deflation,

setting an inflation target of 2%

There is every reason to believe that Japan’s strategy for rejuvenating its economy will succeed

Joseph E. Stiglitz, Project Syndicate 25 April 2013

Japan

While experimental monetary policy is now widely accepted as standard operating procedure in today’s post-crisis era,

its efficacy is dubious

Stephen S. Roach, Project Syndicate 25 April 2013

"As president Ronald Reagan’s secretary of the Treasury, I abhor the idea of government ownership.

Unfortunately, we may have no choice.

US may be repeating Japan’s mistake by viewing our current banking crisis as one of liquidity and not solvency.

Most proposals advanced thus far assume that, once confidence in financial markets is restored, banks will recover.

James Baker, Financial Times March 1 2009

The new management of the BoJ must consider a wider menu of asset purchases, including monetisation of government deficits.

Richard Werner of Southampton University has long argued that fiscal monetisation would best come from direct borrowing by the government from banks.

Martin Wolf, FT March 5, 2013

At the limit, Japan might use “helicopter money”, as discussed in my column of 12 February.

If the BoJ uses fiat money it does not wish to withdraw, it will also have to impose explicit reserve requirements on commercial banks.

At the heart of Abenomics lies a simple, and entirely orthodox, proposition:

that deflation is a monetary phenomenon.

In Japan, where prices as measured by the gross domestic product deflator have fallen 18 per cent since 1994

David Pilling, Financial Times, 20 February 2013

... a news report quoted a senior G-20 official as saying language in an earlier G-7 statement vowing members

“will not target exchange rates” had run afoul of China — a member of the G-20 but not the G-7.

In the end, the G-20 statement amended the language to read:

“We will not target our exchange rates for competitive purposes…”

MarketWatch 18 February 2013

Let me be clear that the exchange rate is not a policy target,

but it is important for growth and price stability,"

Draghi said, CNBC 18 February 2013

Japan

For three years economic policy throughout the advanced world has been paralyzed, despite high unemployment, by a dismal orthodoxy.

Every suggestion of action to create jobs has been shot down with warnings of dire consequences. If we spend more, the Very Serious People say, the bond markets will punish us. If we print more money, inflation will soar. Nothing should be done because nothing can be done, except ever harsher austerity, which will someday, somehow, be rewarded.

Paul Krugman, New York Times, 13 January 2013

Vi lever med våra etablerade sanningar

Det är antaganden som sällan eller aldrig ifrågasätts, därför att vi intalar oss att de måste vara korrekta

En sådan så kallad sanning är att Japan fullständigt misslyckats med hanteringen av sin finanskris som bröt ut kring 1990

Peter Wolodarski Signerat DN 13 januari 2013

Suddenly it is game on in Tokyo – and the world is watching.

For the past 15 years Japan has been trying to shrink its way out of its problems. That did not work.

Now it is about to try the opposite approach.

Financial Times January 11, 2013

Many ask whether high-income countries are at risk of a “double dip” recession. My answer is: no,

because the first one did not end. The question is, rather, how much deeper and longer this recession or “contraction” might become.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 30 August 2011

U.S. government bond yields are poised to converge with Japan’s for the first time in almost two decades,

sparking the biggest returns for investors in Treasuries since 2008

while raising concern that America may be stuck in a prolonged period of below-par economic growth.

Bill Gross, Bloomberg Aug 15, 2011

A question (to which I don’t have the full answer):

Why are the interest rates on Italian and Japanese debt so different?

As of right now, 10-year Japanese bonds are yielding 1.09 %; 10-year Italian bonds 5.76 %

Paul Krugman, July 16, 2011

The case for co-ordinated yen intervention

Gavyn Davies March 17, 2011 (nice charts)

Japanese inflation has been running at least 2 per cent below the world average for many years, and of course the dollar itself has fallen against most other currencies. Therefore, as the graph below shows, the real value of J.P. Morgan’s effective yen exchange rate index, and the competitiveness of the manufacturing sector, is about at its long term average.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz said the European Union may face a “lost half-decade” similar to that experienced by Japan

as governments implement budget cuts that may undermine the economic recovery.

Joseph Stiglitz, Bloomberg Mar 8, 2011

“Is there a bond bubble in Japan? Because if there is, it has somehow lasted for 20 years.

If you don’t get legitimate economic growth, then there isn’t a bond bubble.”

It is fitting that on September 15 Japan, the world's only major economy battling actual deflation, initiated what has come to be a global round of quantitative easing.

Quantitative easing involves a central bank creating money to buy securities, adding reserves to the banking system, and hoping to increase lending and economic activity in the process.

By John H. Makin AEI Online October 2010

As the policy debate intensifies, investors might spare a thought for Korekiyo Takahashi,

Bank of Japan governor from 1911 to 1913.

Gillian Tett, FT September 2 2010

He also served as finance minister and prime minister in the 1920s and 1930s.

Outside Japan, few western investors know the name. For while there is discussion about what can be learnt from Japan’s lost decade, little attention has been paid to earlier periods.

The experience of 1930s Japan is thought-provoking. Not only does it help explain the decisions that Tokyo leaders took during the lost decade; it offers a cautionary tale about exit strategies.

A Keynsian by instinct Takahashi reversed the tough, deflationary stance of his predecessor and fought recession with massive stimulus: he abandoned the gold standard, loosened credit conditions and raised public spending, financed with new debt.

In some ways, it worked. As the yen lost 40 per cent of its value, exports boomed. Then, as annual public spending rose above 50 per cent of GDP, or almost double the 1929 level, Japan’s economy stabilised, even as the US continued to ail.

When the private sector is deleveraging even with zero interest rates, the economy enters a deflationary spiral as it loses aggregate demand equal to the sum of unborrowed savings and debt-repayments every year.

If left unattended, the economy will continue to contract until either private sector balance sheets are repaired, or the private sector has become too poor to save any money (=depression).

The last time this deflationary spiral was allowed to materialise was during the Great Depression in the US.

Richard Koo, Chief economist, Nomura Research Institute, The Economist Jul 26th 2010

We aren’t Greece. We are, however, looking more and more like Japan.

Paul Krugman NYT 20 may 2010

What about near-record unemployment, with long-term unemployment worse than at any time since the 1930s? What about the fact that the employment gains of the past few months, although welcome, have, so far, brought back fewer than 500,000 of the more than 8 million jobs lost in the wake of the financial crisis? Hey, worrying about the unemployed is just so 2009.

But the truth is that policy makers aren’t doing too much; they’re doing too little. Recent data don’t suggest that America is heading for a Greece-style collapse of investor confidence. Instead, they suggest that we may be heading for a Japan-style lost decade, trapped in a prolonged era of high unemployment and slow growth.

Low inflation, or worse yet deflation, tends to perpetuate an economic slump, because it encourages people to hoard cash rather than spend, which keeps the economy depressed, which leads to more deflation. That vicious circle isn’t hypothetical: just ask the Japanese, who entered a deflationary trap in the 1990s and, despite occasional episodes of growth, still can’t get out. And it could happen here.

Japan’s experience strongly suggests that even sustained fiscal deficits, zero interest rates and quantitative easing will not lead to soaring inflation in post-bubble economies suffering from excess capacity and a balance-sheet overhang, such as the US.

It also suggests that unwinding from such excesses is a long-term process.

Martin Wolf, January 12 2010

Will America follow Japan into a decade of stagnation?

The Economist print August 21st 2008

Could the credit crunch destroy the Eurozone?

The historical precedent is not the Great Crash of 1929. Rather, it is the Japanese property bubble of 1989 and the deflation and long-term stagnation which followed.

Some readers will recall a time in 1988 when it was claimed that the value of a few square kilometres of real estate in Tokyo exceeded the assets of the US state of California.

George Irvin, EU Observer, 31/7 2008

The author is Professorial Research Fellow at the University of London, SOAS, and author of ‘Super Rich: the growth of inequality in Britain and the Unites States' (Cambridge: Polity)

The bursting of the Japanese property bubble brought with it a similar credit crunch, and fearing the worst, Japanese households cut their spending thus sending the economy deeper into recession. The Bank of Japan initially did the right thing, flooding the market with liquidity and holding nominal interest rates close to zero. But in the early 1990s, price levels started to fall - causing consumers' nominal debt to rise in real terms and leading them to postpone consumption even more. The result was nearly two decades of stagnation. As Keynes recognised, there comes a point when the use of monetary policy alone is as ineffective as ‘pushing on a string'.

The fourth point - following logically from the third - is that Keynesian fiscal policy is very relevant today. Ultimately, when nobody else is willing to spend and when credit is tight, it is government which must spent its way out of the crisis. This was the lesson of the 1930s and 40s, the lesson in Europe of Marshall and the the trente glorieuses, the lesson of Japan, and it is still the lesson today.

The Eurozone is vulnerable to crisis because of the lop-sided nature of its economic governance - a powerful central bank, but a tiny, non-adjustable EU budget, with fiscal spending at member-state level constrained by the SGP.

/SGP?

Stabilitetspakten/

In this sense, the US is far better equipped to combat recession; its Central Bank is required to treat inflation as only one of three criteria, while Congress has discretionary power to use the federal budget counter-cyclically; eg, it accepted George Bush's reflationary package worth 1% of GDP, however poorly targeted the package may have been. The EU has no such discretion, but instead is bound by rules-driven automatic stabilisers inspired by bankers' notions of ‘sound money'.

True, when the downswing really starts to hurt the ECB still retains plenty of scope to cut interest rates.

But what happens when monetary policy becomes ineffective. In truth, Brussels will need to reconsider Keynes and the Eurozone's economic architecture will need to alter drastically,

or else the very existence of the Eurozone will be in peril.

For pro-Europeans like myself, that is the harshest lesson of the present crisis.

See also: http://eubookshop.com/När och hur spricker EMU?

EMU Collapse

Click here

That’s not to suggest that there is no room for coordination between the monetary and fiscal authorities. This is particularly the case when the economy is experiencing asset deflation, begetting debt deflation and deleveraging. Indeed, none other than Chairman Bernanke made this case when he was Governor, first in November 2002 in his famous speech titled

“Deflation: Making Sure ‘It’ Doesn’t Happen Here”,

and then in May 2003, in a speech titled “Some Thoughts on Monetary Policy in Japan”3.

The Paradox of Deleveraging

Paul McCulley, July 2008

Hillary Clinton is one of several prominent figures to warn that the US “might be drifting into a Japanese-like situation”.

Three factors distinguish Japan’s long malaise from the present US crisis:

the source of the problem, the size of the problem and the response of policymakers.

Richard Katz, Financíal Times April 21 2008

Japan’s experience in the late 1980s and early 1990s has become a fascinating empirical

Ronald McKinnon and others have argued that Japan’s mistake was to

submit to pressure from the United States and other countries to allow yen appreciation,

which was followed by more than a decade of deflation in Japan.

Paul McCulley and Ramin Toloui November 2007

How much the world has changed, and not for the better,

due to the irresponsible behavior on the part of the Bank of Japan and Alan Greenspan's Federal Reserve

over the past 20 years or so.

Bill Fleckenstein 6/8 2007

Bank of Japan acted foolishly throughout the 1980s, which caused that country to experience enormous real-estate and stock bubbles. Japan's stock bubble was really a residue of its real-estate bubble - actually a credit bubble

After Japan's problems, that nation's central bank kept interest rates at virtually zero for the better part of a decade. That essentially-free money has been part of the reckless lending and misallocation of capital that has proliferated around the planet.

In the years since our equity bubble peaked, trillions of dollars' worth of debt have piled up throughout corporate America. So now, as we enter recession, we will experience not just a weak economy, real-estate market and stock market, but the exacerbating effect of a mountain of bad debt, completing the analogy to Japan of the 1990s.

Amazing similarity between the last month or so

of the rise in Japan that ended on Dec. 29, 1989,

and the current advance in the Dow Jones

Bill Fleckenstein, CNBC 7/5 2007

In retrospect, Japanese officials made several important policy errors.

In order to avoid further yen appreciation after the 1987 Louvre agreement, they followed easy monetary and financial policies that gave rise to huge asset price bubbles and expansions in credit that set the stage for the subsequent downturn.

Lawrence Summers, FT February 25 2007

They failed, at a moment when consumers were enjoying record increases in wealth, to encourage a shift to domestic demand-led growth. They also allowed problems in the banking system to fester rather than confront them directly. The result of these mistakes was that Japan did less than it could have done to prevent the serious problems of the 1990s and was not well positioned to address them when they arose.

Louvre Accord

An agreement reached in February 1987 by the five countries which comprise the G-5 (France, West Germany, Japan, the UK and US) following an earlier decision to correct an overvalued $US. They agreed that the $US had fallen sufficiently and that they would take steps to ensure stability in exchange rates.

Statement of the G6 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors (Louvre Accord)

Why the subprime bust will spread

The Bank of Japan's zero-interest policy, combined with general asset deflation in the yen economy, has caught the Japanese insurance companies in a financial vise. Both new loan rates and asset values are insufficient to carry previous long-term yields promised to customers.

Henry C K Liu

Japan raised interest rates to 0.5%

In July last year, the bank raised the rate to 0.25% following six years of zero interest rates

Financial Times 21/2 2007

Raising rates 25 basis points barely moves the needle on the carry trade, since volatility is low and yawning differentials still exist with the leading currencies. Indeed, further tightening is on the cards in Europe, as well as Australia and New Zealand – favourite carry trade currencies.

Christopher Wood and Brian Reading 15 years ago correctly predicted Japan's era of stagnant growth and bear markets.

Bloomberg, March 20, 2007

Now both are making another contrarian call: The Bank of Japan should raise interest rates. Wood, chief equity strategist at CLSA Ltd., and Reading, a director at Lombard Street Research, say that higher rates would boost interest income for the world's biggest savers.

The two men, who have never worked together, also say an increase would make banks more profitable, boost stock prices and end a decade-long fight against deflation.

``People will come to accept the view that Japanese interest rates should normalize,'' said Hong Kong-based Wood, 49. His book, ``The Bubble Economy,'' was published in October 1992, more than a decade before the Nikkei 225 Stock Average hit a 20- year low. ``However, I have zero confidence that this will occur in the next three months.''

Traditional economics suggests that higher borrowing costs slow the economy by curbing lending and consumer spending. Japan's central bank left interest rates unchanged following the conclusion of its meeting today, a move expected by all 49 economists surveyed by Bloomberg.

Reading, whose June 1992 book was entitled ``Japan: The Coming Collapse,'' agrees with Wood's views that higher rates would lift spending rather than damping it. ``One of the greatest fallacies today is that higher Japanese interest rates depress demand,'' he said.

The last time an emerging economic powerhouse in Asia agreed to let their currency strengthen. It was the Japanese Yen and the 1985 Plaza Accord resulted in it strengthening by more than 50 percent against the U.S. dollar in a period of just two years.

This augered in one of the most horrific booms and busts the world has ever seen and Japan has still not recovered after fifteen years. It's not likely that the Chinese will repeat this mistake, despite what a bunch of smart people from Washington tell them.

Tim Iacono 17/12 2006

OECD gave warning that Japan - the world's second-biggest economy - was still too fragile after years of debt deflation to risk a rapid rise in rates from 0.25pc. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Daily Telegraph 1/12 2006

Japan ends zero-rate policy after six years

FT July 14 2006

The Bank of Japan on Friday raised interest rates for the first time in nearly six years, ending an extraordinary period of zero interest rates aimed at breathing life back into the Japanese economy.

The US monetary base has been growing fairly steadily and in line with US GDP growth. If one wants to blame a central bank for volatility in global monetary aggregates, one should instead turn to Japan.

The Yen Carry Trade & the New Yield Curve

Gavekal 8/5 2006

Founded in 1999 by Charles and Louis-Vincent Gave and Anatole Kaletsky, GaveKal is a global investment research and management firm

Japanese monetary base is now larger than the US'. That is quite impressive for an economy less than half the size.

QE, ZIRP and Exchange Rate Stability

The most recent increase in money supply (policy of quantitative easing) was preceded by two others policies:

1. Short rates were been maintained at, or close, to zero since 1996

2. A deliberate attempt was introduced to maintain the Yen spot exchange rate more or less stable around the US dollar in a band of ¥105-120/US$.

if the central banks are serious about taming the global inflationary pressures, then the tightening now has to happen in Japan. In a sense, this tightening has already begun: the policy of QE has been abandoned and the growth rate of the Japanese monetary base is now negative.

In 1974 and 1987, the end of the Japanese monetary expansion and the return to the norm led to a sharp increase in market volatility. Should we expect the same thing again? We reiterate our recommendation to buy Yen calls to hedge "at risk" positions in portfolios.

After 15 years, Japan's economy is growing again,

which means the Bank of Japan won't be flooding global markets with free money.

The problem is that during Japan's lost decade, the world has gotten hooked on ridiculously cheap Japanese cash sloshing around the financial markets.

Jim Jubak, CNBC, March 14, 2006

It's officially over. After 15 years - yes, 15 years - of no growth, Japan's economy is poised to grow by as much as 5% in 2006. After eight years of slowly but steadily falling prices, Japan can now smell a welcome whiff of inflation.

The recovery in Japan is likely to usher in hard times in financial markets and economies around the globe. And no economy is at greater risk of taking a body blow from a Japanese economic recovery than that of the United States.

This effort took many forms. In September 2002, for example, with the Nikkei 225 stock index at 9,000 - down more than 75% from its high of nearly 38,916 at the end of 1989 - the Bank of Japan started to buy shares in troubled companies to keep the Japanese stock market from sliding even further. To keep the market for Japanese Treasury bonds functioning smoothly, the bank also bought government bonds. And in an effort to flood the financial markets with free money in the hope that somebody would borrow it if it was just cheap and plentiful enough, the Bank of Japan bought billions in short-term debt.

Some of the cash was borrowed in Japan by overseas investors who used the free money to buy U.S. Treasurys, gold and mortgage-backed securities, among other assets. This carry-trade, as it's called, is extremely profitable because access to free money means that investors can leverage their own cash with borrowed money to the tune of 5 or 10 or 20 to one.

Japan emerges from deflation. The Bank of Japan responds by ending "quantitative easing",

its policy of flooding the banking system with economy-buoying liquidity.

Everyone is delighted that Japan's economy has improved sharply, that growth seems entrenched and that deflation looks beaten. But ...

Chris Giles, Financial Times Economics Editor, FT 10/3 2006

Stephen Roach, chief economist of Morgan Stanley and a long-standing pessimist about the world economy, wrote this week that "the biggest news in close to a decade is that the BoJ now appears to be on the cusp of abandoning its policy of über-accommodation".

It could halt the "carry trade" in which international investors borrow for nothing in Japan and buy assets elsewhere. It could also encourage Japanese people to invest their money at home rather than abroad on the expectation of higher returns.

Through a series of steps - the end of the carry trade, less investment in US assets, higher yields on Treasury bonds, more expensive US mortgages and falling US house prices - Mr Roach sees the end of quantitative easing as a potential catalyst for the bursting of a US housing bubble and a halt to consumer-led growth. This view, however, is far from mainstream.

Japan is back

Is this then the reward for Junichiro Koizumi's reforms? "Exactly the opposite" is the answer. If the prime minister had done what he initially proposed - pursue structural reform and cut fiscal deficits - the result would have been a catastrophe.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times 8/3 2006

The collapse of the bubble economy left Japan with a stupendous hangover. As Richard Koo of Nomura Securities noted in a book published in 2003 - Balance Sheet Recession, John Wiley & Sons - the fall in Japanese asset prices, particularly land, lowered the total value of all assets by a sum equal to 2.7 times 1989 GDP. This was a far bigger loss, relative to GDP, than that suffered by the US in the great depression of the 1930s. It was only because of Japan's fiscal expansion and loose monetary policy that a comparable outcome was avoided. Moreover, as the government took on ever more debt, the private corporate sector (financial and non-financial) was able to clean up its own balance sheets, thereby laying the ground for today's recovery.

Skyll Japankrisen på Keynes

Mattias

Lundbäck SvD ledarsida 2002-01-11

Bo Lundgren i Veckobrev 22 februari

2002:

På söndag åker jag till Tokyo för att

diskutera den japanska och asiatiska ekonomin med

regeringsföreträdare, akademiker och representanter för

näringslivet.

Japanese banks on a downward spiral

Financial Times, January 28 2002 18:19

Japan in Depression

By John H. Makin

January 2002

A world without easy money

Martin Wolf

Financial Times, Dec 11 2001

Japan hears bank bailout whispers

BBC 20 February, 2002

After what most observers have derided as a lacklustre visit to Japan by US President George W Bush, the focus of attention has shifted to media reports of an impending bank bailout.

The Nihon Keizai Shimbun, whose official sources are generally seen as reliable, said that Bank of Japan Governor Masaru Hayami has been increasing pressure on the government to act.

The paper reported a meeting on Tuesday evening in which Mr Hayami urged Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi to inject up to 10 trillion yen ($75bn; £52bn) into the banking system.

He also espoused further relaxation of the bank's monetary policy beyond its current ultra-loose status.

Japanese banks on a downward spiral

Financial

Times, January 28 2002 18:19

It says much about attitudes to Japanese banks these days that, when Standard & Poor's chief credit officer for Asia-Pacific recently described the banking system as "technically insolvent", his comments caused barely a ripple among his audience.

That is because most experts without a vested interest in saying otherwise agree that the world's second biggest banking system is essentially bust.

This realisation is confronting Junichiro Koizumi, the prime minister, with an acute policy dilemma and may yet force him into an embarrassing policy U-turn. While Mr Koizumi has talked tough about injecting market disciplines into the Japanese economy and capping government debt issuance, he may soon be forced to resort to an old-fashioned government bail-out of the banking industry.

That is not all. Banks' core capital, while technically meeting regulatory requirements, has been padded with preferential shares (the legacy of previous government cash injections that must be repaid), as well as deferred tax income on profits that are unlikely ever to materialise. If these are stripped out, says Fitch Ibca, a ratings agency, most institutions will fail to meet Basle capital adequacy criteria. Some will even have negative capital.

The financial problems of the banks are due not only to their past lending decisions and their inability to write off bad debt. They are also having difficulty making enough money in interest on loans because short-term interest rates are practically zero. A gloomy Bank of Japan official points out that, with the overnight call rate at just 0.001 per cent, a bank that lends Y10bn will make a profit of Y278. That is not enough to buy a cup of coffee, let alone to cover the cost of making the loan.

As a result, banks have largely ceased to perform their function of credit creation. Last year, an increasingly desperate BoJ increased the base money supply by 16.4 per cent. But the flood of yen made little difference to the real economy: money supply stagnated, while bank lending and consumer prices continued on their third straight year of decline.

Skyll Japankrisen på Keynes

Mattias

Lundbäck SvD ledarsida 2002-01-11

I nyhetsbrevet Economic Outlook från American Enterprise Institute varnar ekonomen John H Makin för att Japan är på väg in i en lånefälla. Deflationen, som är en konsekvens av enögd keynesiansk stimulanspolitik, har lett till att värdet av alla skulder successivt har ökat i den japanska ekonomin. Nu håller situationen på att bli ohållbar.

Japans ekonomiska politik kommer att gå till de ekonomiska historieböckerna som en tragisk bekräftelse av att Keynes kritiker, bland andra Milton Friedman och Robert Barro, hela tiden har haft rätt.

Japan in Depression

By John H. Makin

January 2002

The negative net worth of the Japanese banking system is somewhere above the yen-equivalent of $1 trillion. When the banking system collapses, in order to avoid compound losses by Japan's households, the Bank of Japan will need to inject at least $1 trillion into the banks to protect depositors from losses that would constitute a further setback for the Japanese financial system and economy.

A world without easy money

Martin Wolf

Financial Times, Dec 11 2001

The US in the 1930s and Japan in the 1990s were the 20th century’s most spectacular examples of post-bubble economies. Mr King argues that it is particularly difficult for very large economies to grow out of post-bubble corrections, because they cannot easily use the rest of the world as a source of demand. The US can hardly do so today.