-

-

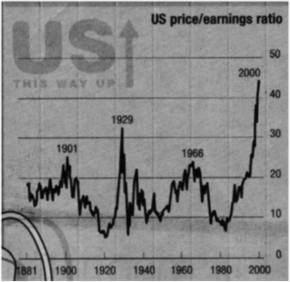

Alan Greenspan om "irrational exuberance" - "Nu har det vänt"

Martin Wolf - Klas Eklund - U.S. Trade Deficit

Financial Crisis in Japan - Financial Crisis in Asia - Financial Crisis in Sweden

Nouriel Roubini's Global Macroeconomic and Financial Policy Site

(ranked as the #1 Web Site in Economics in the world by The Economist Magazine)

See also: The Next Bubble - House prices

This site offers updated information relating to the book Irrational Exuberance by Robert J. Shiller

-

-

Mr Greenspan was not certain that the equity market was indeed a bubble. But by September, he was explicitly referring to it in such terms: "I recognise that there is a stock market bubble problem at this point," he said at the September 24, 1996 meeting - the day the Dow closed at 5874.03.

Three years ago, at the height of the stock bubble, Paul Volcker, Mr Greenspan's predecessor as Fed chairman, issued a famous warning: that the world economy was dependent on the US economy, which was dependent on the stock market, which was dependent on fifty stocks, half of which had never reported any earnings. (FT.com site; Jul 19, 2002)

A stock market bubble exists when the value of stocks

has more impact on the economy than the economy has on the value of stocks

John Makin

November, 2000

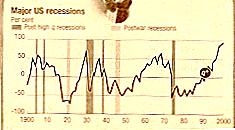

The root cause of this recession

was the bursting of one of the biggest financial bubbles in history.

It is

wishful thinking to believe that such a binge can be followed by one of the

mildest recessions in history—and a resumption of rapid growth.

The

Economist January 2002

Market crashes through

the ages

BBC 16 July, 2002

Gerhard Stenberg, chef för Handelsbankens

kapitalförvaltning i Göteborg, hoppar av i protest mot

börshysterin efter nästan 30 års arbete i aktiemarknaden.

98-05-20

Han tror att en börskrasch är oundviklig och vill inte

ta ansvar för att rekommendera placeringar i aktier för

närvarande. "Kurserna är på tok för höga och

måste ned med minst 30 procent.

Vi står

inför ett kraftigt fall i börskurserna i hela världen. Det

kommer att bli en rejäl smäll".

Vad kan man lära av

historien?

Rolf Englund i Smedjan nr 4/1992

-

-

Spela

roulett med skuldbördan

Leif Widén

(Världsekonomin

och aktiebörserna)

Arbetspapper 2002-02-04

Tröstande ord från Gunnar Eliasson - sju procent realt per år - på sikt

Aktieindex Hongkong och London 1993-1997

Doomsday-warnings

See also New Era?

The Internet Stock Mania Website

US unemployment claims, continued claims

1983 -

2002

Over two days this week, Gerrit Zalm, the Netherlands finance minister, and Nicolas Sarkozy, his French colleague, have set up a live experiment that will assure full employment for future graduate students of comparative economics.

Financial Times editorial 23/9 2004

The intriguing question facing eurozone policy makers is whether the two ministers, with their very different budgetary prescriptions for 2005, can boost employment more broadly in their economies while bringing their deficits below the limit of 3 per cent of gross domestic product set by the EU's stability and growth pact.

The policies could not be more different. Mr Zalm, with determined rigour, has brushed aside street protests to present a hair-shirt, supply-side budget which combines belt-tightening for consumers and corporate tax breaks for business. He hopes the deficit will fall to 2.6 per cent next year from 3 per cent in 2004 and structural reforms will attract investment, creating growth and jobs in the medium term.

Mr Sarkozy's budget, by contrast, appears largely pain-free. Buoyed by a recovery in government revenues, the French finance minister forecast that the public finances next year would show a deficit of 2.9 per cent - meeting EU rules for the first time since 2001.

An International Monetary Fund study, released last night, suggested that fiscal policy in the eurozone has weakened since the introduction of the single currency in 1999.Against this background, it is difficult not to sympathise with Jean-Claude Trichet, the European Central Bank president, who warned again yesterday of the need for further budget consolidation and the dangers of loosening the stability pact's sanctions against excessive deficits.

What is the relationship between Weimar Germany and Wall St. of the late 90s?

On the surface, what could be more different?

Stock market booms are the best of times while hyperinflation is a nightmare.

Robert Blumen, Ludwig von Mises Institute

During the year ending in July, real disposable income grew at a 1.8 percent rate while real consumer spending grew at a 3.5 percent rate.

John Makin, AEI

Hans Tson Söderström: Tur att vi har vår flytande krona

Det är inte särskilt höga odds på tipset att efter det amerikanska presidentvalet följer en kraftig finanspolitisk åtstramning. I värsta fall blir den förknippad med stigande räntor och en fallande dollar.

I så fall uppstår en svårbermästrad situation för ECB och EU:s finansministrar

Kolumn i DI 10/9 2004

Stand by for a pensions bail-out

A re-run of the S & L disaster

John Plender Financial Times 13/9 2004

In the light of United Airlines' proposal to stop contributing to its pension funds, comparisons are increasingly being made between today's overstretched US pension fund system and the savings and loans crisis of the 1980s. Not without justice, although the problem in pensions will be more of a slow-burn affair since pension funds, unlike S & Ls, are unleveraged.

The nub of it is that private defined benefit schemes in the US have a $400bn funding gap. Meantime, the Pensions Benefit Guarantee Corporation (PBGC), the agency that insures private pensions for 44m workers and retirees, had an $11.2bn deficit at the end of 2003. It also has $85bn in exposure to companies with junk bond ratings, which implies a high risk of default.

The position can only worsen given the degree of moral hazard built into the system, whereby the premiums paid to the PBGC do not adequately reflect the risks. One measure of this, highlighted by Bradley Belt, executive director of the PBGC, is the fantastic bargain United Airlines has enjoyed at the insurer's expense. It has paid little more than $50m in premiums since the agency's inception in 1974. Yet if its pension plans terminate, the PBGC would be hit by a claim of $6.4bn.

The agency is thus in a position not unlike that of the International Monetary Fund. Its mere existence encourages morally hazardous behaviour and everyone expects it to act as a financier of last resort for the whole system. Yet it lacks the resources to do more than a marginal firefighting job in the event of a systemic crisis. And the potential for systemic crisis increases all the time because the weaker players in the system are encouraged, as in the S & L fiasco, to speculate their way out of trouble.

More by John Plender at FT site

"Risk för global kris"

Morgan Stanleys chefsekonom varnar för sammanbrott i världsekonomin

DN 9/9 2004 Reporter Johan Schück

När andra talar om ljusare tider, så menar han /Stephen Roach/ att skenet bedrar och att problemen bara skjuts på framtiden.

- De amerikanska konsumenterna håller igång ekonomin genom att skuldsätta sig allt djupare, uppmuntrde av skattesänkningar och rekordlåga räntor.

Räntorna är konstlat låga och måste upp till mera normala nivåer.

Numera är det inte privat kapital, utan pengar från centralbankerna i Ostasien /läs: Kina och Japan/ som täcker det amerikanska /bytesbalans/underskottet.

Roach tar tillbaka sitt råd från tidigare i år om en kraftig amerikansk räntehöjning: ekonomin är inte längre tillräckligt stark, det rätta tillfället har gått förlorat, menar han.

"USA har ryckt åt sig ett stort försprång och har världens mest framgångsrika ekonomi"

Klas Eklund på SvD:s ledarsida 2000-08-11

The risks ahead for the world economy

Fred Bergsten The Economist print edition Sep 9th 2004

Fred Bergsten is director of the Institute for International Economics in Washington.

His book, “The United States and the World Economy: Foreign Economic Policy for the Next Administration” is forthcoming.

Very Important Article

Bubbles are getting blown out of all proportion

The financial press is full of grim prognostications of economic damnation postponed but not avoided.

The monetary moralists preaching inevitable doom for the US economy because the Fed dared to stabilise the economy after the bubble's collapse are simply wrong

Adam Posen Financial Times 8/9 2004

The writer is a senior fellow at the Institute for International Economics

Chart sources: Author’s calculations from Adam Posen ‘It Takes More Than A Bubble to Become Japan’ (Reserve Bank of Australia 2003)

Like the hellfire preachers of yesterday, today's economic pundits are taking a stern line on excess. Economies that enjoyed asset price booms, notably the US, are damned to pay for their wanton ways. Central banks that attempted to offset the negative effects of a bubble's burst, notably the US Federal Reserve, are merely postponing the day of judgment and, if anything, compounding their sin by blowing up other bubbles - in housing, or in government bonds, or both. The financial press is full of grim prognostications of economic damnation postponed but not avoided.

This is all pernicious (pernicious \pur-NISH-us\, adjective:

Highly injurious; deadly; destructive; exceedingly harmful/nonsense). Pernicious because it discourages central banks from responsibly doing their job of stabilising the real economy, as the Fed correctly did in 2001-03.

Nonsense because there is no evidence to support these claims. Bubbles have only rarely caused the lasting damage that these commentators assert as unavoidable destiny; when they have, it has been because central banks have failed to respond to the bubbles' aftermath.

The outdated but apparently still widely attractive monetarist image of liquidity as toothpaste - if you squeeze the tube in one place, it bulges somewhere else - does not stand up empirically.

This cross-national evidence is consistent with economic historians' assessments of the US experience. Among the many booms, panics and busts in the 19th and 20th centuries, only those accompanied by banking problems had negative consequences lasting beyond a few quarters. Bubbles can pop with limited macroeconomic impact, and usually do.

As for the second contention, the moral hazard story of “the Greenspan put” - in which investors believe the Fed will step in to protect them if the market crashes, and so act recklessly - is a cute story, but that is all it is. Investors do not decide whether or not to risk their money based on whether the central bank cut rates in the aftermath of the last bubble.

In fact the evidence is that, if anything, investors have less risk tolerance for extended periods after bubbles, whether or not the central bank cuts rates. Only two of the 15 big industrial economies (Finland and Italy) have had recurring bubbles since 1970 - all the rest had to wait through a long period of fading memories and turnover in financial services personnel before a second asset price boom emerged (if one ever did).

Deflation did not emerge in Japan until the end of 1997, many years after the bubble had burst. It was a consequence of years of failure by the Bank of Japan to respond adequately to slowing growth, the Ministry of Finance's decision to raise taxes in a recession and the corporate sector's inability to face up to bad loans, a problem that was allowed to grow to vast proportions. After the bubble burst, the BoJ's unwillingness to stimulate the economy unless government and business “got the rot out” served only to encourage more wasteful government spending, greater declines in corporate and bank capital and constant renewal of bad loans.

Thankfully, the Fed, as its aggressive rate cuts in 2001-03 show, has learnt these lessons. The monetary moralists preaching inevitable doom for the US economy because the Fed dared to stabilise the economy after the bubble's collapse are simply wrong.

All reasonable people agree that today, with rising inflation, burgeoning Federal deficits and the possibility of a stagflationary oil shock, interest rates should be on an upward path in the US. But the Fed is right to wait for the data to come in to determine the pace of that increase.

America on the comfortable path

to ruin

These two facts - the rest of the world's surplus output and

the US goal of full employment - explain the global macro-economic picture

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, August 18 2004

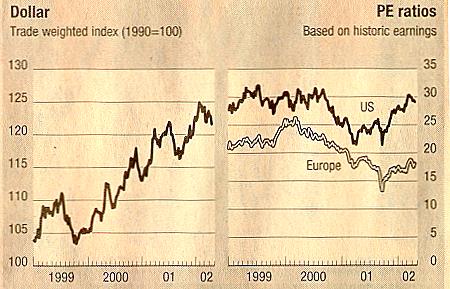

From 1996 to 2003 US real demand has grown faster than real gross domestic product in every year (see chart). When demand has grown slowly, as in 2001, output has grown even more slowly. Thus, the US authorities had to generate faster growth of demand than of potential output, with the difference spilling over on to the rest of the world via growing current account deficits.

Was the fiscal slide inevitable? No, but it could have been avoided only if the US had been prepared to accept a slump. Yet no US administration would have tolerated this outcome.

For the same reason, the desire of both presidential candidates to reduce the fiscal deficit in coming years is meaningless without change in the external position. The point is powerfully made in the latest in a series of papers authored by Wynne Godley and associates for the Levy Economics Institute and the Cambridge Endowment for Research in Finance. click here

Let us be blunt about it. The US is now on the comfortable path to ruin. It is being driven along a road of ever rising deficits and debt, both external and fiscal, that risk destroying the country's credit and the global role of its currency. It is also, not coincidentally, likely to generate an unmanageable increase in US protectionism.

Worse, the longer the process continues, the bigger the ultimate shock to the dollar and levels of domestic real spending will have to be. Unless trends change, 10 years from now the US will have fiscal debt and external liabilities that are both over 100 per cent of GDP. It will have lost control over its economic fate.

What cannot last will not do so, as the late Herb Stein famously remarked.

The essence of the needed changes is quite clear: a further substantial devaluation of the dollar, together with a sizeable rise in domestic demand, relative to potential output, in almost all other important economies of the world.

See also FT leader: Dollar stands

on a precipice

Financial Times; Jan 02, 2003

As the late Herbert Stein,

former chairman of the US council of economic advisers, once said:

"If

something cannot go on forever, it will stop."

The combination of an ever-rising US current account deficit with a strong dollar must cease. Indeed, it already is doing so. The currency weakened in 2002. It is rather likely to weaken further in 2003. The present course of the US economy is unsustainable.

Net US liabilities to the rest of the world are some 25 per cent of gross domestic product - in the neighbourhood of $2,500bn (£1,562bn). In the first three quarters of 2002, the current account deficit ran at close to five per cent of GDP. As recently as 1997, however, the deficit was only 1.5 per cent of GDP. It is bigger this year than two years ago, despite last year's economic slowdown. Since the beginning of 1997, trend growth of exports of goods and services, at constant prices, has been 2.2 per cent a year, of GDP 3 per cent and of imports 7.4 per cent. Even under quite conservative assumptions, the current account deficit could, on current trends, be over 7 per cent of GDP by 2007. By that year, US net external liabilities would, at current exchange rates, be close to 65 per cent of GDP. If the dollar is to remain strong, despite these deficits, the rest of the world must accumulate net claims on the US economy at $500bn a year, and rising, for the indefinite future. This is hard to imagine.

Already, there has been a steep decline in net private foreign purchases of US assets, from $978bn in 2000 to an annual rate of just $560bn in the first three quarters of 2002. Net foreign direct investment has collapsed, from $308bn in 2000 to an annualised $14bn in 2002. This decline in private foreign purchases of US assets has been offset by a big increase in foreign government net purchases of US assets, from $38bn in 2000 to an annualised rate of $136bn in 2002. There has also been a steep fall in US private purchases of foreign assets, from $605bn in 2000 to an annual rate of just $380bn in 2002. If foreign governments stopped propping up the dollar and US investors invested abroad, as before, the dollar would tumble. Other currencies must rise if the dollar is to fall. But the two biggest economies after the US - the eurozone and Japan - are highly dependent on export demand, at least for the moment, while no big economy offers obviously superior returns to those available in the US. Moreover, other governments, particularly in Asia, are desperately unwilling to see their currencies rise against the dollar. The most potent of all large-scale purchaser of dollars is Japan. Its vast foreign reserves, already $395bn at the end of 2001, rose to $461bn by October 2002. With the finance minister talking of a yen exchange rate below Y150 to the dollar and pressure on the Bank of Japan to expand the money supply, further purchases are probable. If the dollar is to fall, the important currency against which this is likely to happen is the euro, since it belongs to the one large entity whose authorities will refuse to buy dollar assets in large quantities. The dollar has already fallen 16 per cent against the euro since the end of January 2002. This slide could easily continue in 2003. This is a tale of irresistible force meeting immovable objects. The force is the growing pile of US liabilities. The objects are the low real returns in other big economies and the unwillingness of many governments to tolerate currency appreciation. In the short term, the objects may win. In the long run, the force will be stronger. The dollar must fall. The longer it remains high, the bigger its fall will be.

Greenspan is running out of buttons to push

Peter Hartcher, Financial Times, August 10

2004

The writer is international editor at The Sydney Morning Herald and

a visiting fellow at the Lowy Institute for International Policy. He is author

of a forthcoming book on Alan Greenspan and Wall Street, entitled Bubble

Man

The US economy has grown reasonably fast since the

second half of 2003 and the general expectation seems to be that satisfactory

growth will continue more or less indefinitely.

The expansion may,

indeed, continue through 2004 and for some time beyond. But... it will

certainly not happen without a cut in domestic absorption of goods and services

by the US which would impart a deflationary impulse to the rest of the

world

Wynne Godley et al, The Levy Economics Institute, July 2004

The US economy has grown reasonably fast since the second half of 2003 and the general expectation seems to be that satisfactory growth will continue more or less indefinitely.

But with the government and external deficits both so large and the private sector so heavily indebted, satisfactory growth in the medium term cannot be achieved without a large, sustained and discontinuous increase in net export demand. It is doubtful whether this will happen spontaneously and it certainly will not happen without a cut in domestic absorption of goods and services by the US which would impart a deflationary impulse to the rest of the world.

There are big medium-term risks ahead

Global macroeconomic imbalances, the impact of a rising Asia, protectionism and

vulnerability to terrorist outrages

Martin Wolf 20/7 2004

Start with some of the elements in the global macroeconomic picture.

The US current account deficit has risen from about 1.5 per cent of gross domestic product to over 5 per cent today. During the recent US slowdown, the current account deficit has, remarkably, continued to rise. This is the opposite of what one would normally expect and of experience in the early 1990s.

A net creditor for most of the 20th century, the US has seen its net

liability position move from a rough balance in 1988 to minus 24 per cent last

year.

Yet, despite a current account deficit of 4.9 per cent of GDP in

2003, net liabilities to the rest of the world fell as a share of GDP. The

tumbling dollar reduced net liabilities by more than the current account

deficit increased them.

On average, according to the International Monetary Fund's latest World Economic Outlook, real domestic demand will have grown at 3.8 per cent a year in the US between 1996 and 2005, while real output will have grown at 3.5 per cent.

The UK has an even bigger discrepancy, at half a percentage point a year. Meanwhile, the eurozone's demand will have grown at a pitiable rate of 1.8 per cent, with output growth of only 2 per cent, and Japan's demand will have grown at a still lower 1.2 per cent, with output growth at 1.5 per cent.

In 2004, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development, the Anglosphere (the US, UK and Australia, but not Canada in this

case) will run a combined current account deficit of $636bn, with the US

deficit alone accounting for $555bn.

Asia's current account surplus

was recorded at $322bn.

The Asset Economy

The

income-driven impetus of yesteryear has increasingly given way to asset-driven

wealth effects. For consumers, businesses, policymakers, and investors, the

asset economy turns many of the old macro rules inside out

Stephen Roach

Morgan Stanley 21/6 2004

The equity bubble of the late 1990s was a transforming event in many ways for the US economy. But there is one lasting implication that stands out above all - an important transition in the character of the American growth dynamic.

The income-driven impetus of yesteryear has increasingly given way to asset-driven wealth effects. For consumers, businesses, policymakers, and investors, the asset economy turns many of the old macro rules inside out. In the end, it could well pose the most profound challenge of all to sustainable recovery in the United States.

The threat of extreme events

Kenneth Rogoff, formerly chief economist of the International Monetary Fund

believes there is a high risk of a housing slump in the US

Samuel

Brittan Financial Times June 18 2004

Kenneth Rogoff, formerly chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, in the May issue of the Central Banker puts his finger on a weakness of official assurances by saying "people tend to resist thinking about low probability extreme events".

There are also dangers that are highly likely, but the timing of which is uncertain.

Mr Rogoff cites the US current account deficit of 5 per cent of gross domestic product, which he, like many others, regards as unsustainable. Suppose, however, this suddenly reverts to balance. For instance, a steep collapse in US house prices could lead to a sharp rise in private savings. Indeed, he believes there is a high risk of a housing slump in the US even though the boom there has not gone as far there as it has in the UK or Australia.

A future correction would need to be accompanied, according to the former IMF economic director, by a drop in the the dollar of over 40 per cent in the short run and in the long run of about 12-14 per cent.

Short-term real interest rates in the Group of Seven countries are still negative. In the US, they are minus 1 per cent. In core euro countries, they are around zero. This compares with a normal historical level of, say, 2 or 3 per cent.

There is also a gap of over 2½ percentage points between prevailing international nominal short-term rates and the rates on 10-year government bonds (an upwardly sloping yield curve). Monetary policy is, in the awful US financial jargon, "behind the curve".

Thinking About ‘Low Probability

Events’

Marshall Auerback June 22, 2004

http://www.prudentbear.com/internationalperspective.asp

America’s vaunted economic “flexibility” is a mirage: it is fundamentally a product of financial engineering and endless debt creation, which has persistently created the image of a dynamic economy, successfully withstanding one shock after another, from the fall out of the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s or the devastating terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

http://www.prudentbear.com/homepage.asp

Beware bursting of the money bubble

David Hale Financial Times May 30 2004 19:30

The financial markets have been hit by shocks from the Middle East over the past few weeks. But the real risk to world markets is that the speculative bubbles and "carry trades" that have developed as a consequence of American monetary policy over the past year will unravel as the US Federal Reserve moves to increase interest rates.

During the Nasdaq bubble of 1998-2000, US interest rates ranged between 4 per cent and 6 per cent. Since June 2003, they have stood at 1 per cent. The advent of such low money market yields has unleashed speculative capital flows to asset classes that played no role in the technology bubble of four years ago.

Warren Buffett

"Vi tror att dollarn kommer

att tappa i värde i förhållande till andra större

valutor"

Inför närmare 20.000 aktieägare på

Berkshire Hathaways årsmöte i Omaha, Nebraska meddelade han

därför sin intention att göra slut på investmentbolagets

ansenliga kassa på 36 miljarder dollar, motsvarande 274 miljarder kronor,

så snabbt som möjligt.

DI 3/5 2004

Warren Buffett, känd som en av de mest inflytelserika investerarna i världen, har alltsedan 2002 varit öppet skeptisk till dollarinvesteringar. Han gillar inte alls den räntepolitik som den amerikanska centralbanken för utan förspråkar i stället räntehöjningar.

73-åringen befarar nu att det redan gigantiska handelsunderskottet i landet kommer att öka ytterligare. Inför närmare 20.000 aktieägare på Berkshire Hathaways årsmöte i Omaha, Nebraska meddelade han därför sin intention att göra slut på investmentbolagets ansenliga kassa på 36 miljarder dollar, motsvarande 274 miljarder kronor, så snabbt som möjligt. "Vi tror att dollarn kommer att tappa i värde i förhållande till andra större valutor", sade Buffett, enligt norska Dagens Naeringsliv.

US Trade deficit

Return from the dead

Just when you thought deflation was the

worry

The

Economist Apr 15th 2004

Remember inflation? Remember fretting about accelerating consumer prices and higher interest rates? Those days may soon be back.

John Makin, resident scholar at the American

Enterprise Institute in Washington:

The blissful combination of higher

growth and lower inflation that has characterized the U.S. economy since last

spring is the inverse of stagflation, the nightmare scenario that followed the

oil shock of 1973-74 Still lower inflation is a distinct possibility.

John Makin AEI 29/1

2004

- We are nearing the end of a benign, unusual period of faster

growth and lower inflation and moving into a period of slower growth and higher

inflation

IHT 15/4

2004

On Wednesday, the government reported that U.S. consumer prices shot up more sharply than expected in March, rising 0.5 percent from a month earlier. Excluding food and energy prices, the rise was still 0.4 percent, the biggest monthly increase in two years. These early signs of a return to creeping price increases — just a few months after the U.S. Federal Reserve pronounced the risks of inflation and of deflation ‘‘almost equal’’ — may put the central bank in a tight spot as pressure grows to raise interest rates sooner than it might like.

‘‘We are nearing the end of a benign, unusual period of faster growth and lower inflation and moving into a period of slower growth and higher inflation,’’ said John Makin, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. ‘‘The resulting whiff of stagflation may force the Fed to raise U.S. interest rates while growth is slowing.’’

Those with a memory of what happens when a bubble

bursts know that, if history is any guide, the bear market that began in 2000

is not over - not by a long shot.

By

Maggie Mahar Financial Times April 11 2004 19:36

The writer is the

author of Bull! A History of the Boom, 1982-1999 (HarperBusiness) What drove

the Breakneck Market - and What Every Investor Needs to Know About Financial

Cycles

amazon.com

How can one conclude that they are wrong? Because the US market has not yet "reverted to a mean". Past experience suggests that when a bubble collapses, a market cannot lay down a firm foundation for the next boom until the pendulum has swung back to its mean, or average price.

Historically, at its mean, the S&P 500 has traded at 17 to 18 times the previous year's earnings, and roughly 14 times estimates for the current year, while yielding dividends of about 4 per cent. When a bear market scrapes bottom, the pendulum inevitably swings too far in the other direction: price-earnings ratios usually sink below 10, while the yield rises to at least 5 per cent.

Today, the S&P 500 fetches approximately 29 times last year's earnings and roughly 18 times estimated earnings for 2004, assuming you believe analysts' estimates. As for dividends, the average stock on the S&P yields less than 2 per cent.

Meanwhile, the underlying economy deteriorates in what could be the prelude to a second fall in equity prices. Debt builds, the dollar declines, capital investment remains sluggish and, despite increased productivity, real wages barely budge. Sceptics argue that a recovery built on debt and consumer spending is no recovery at all.

So the crash of 1929 was followed by a 50 per cent rally. But then came the crash of 1930-1932. When it was all over, the market had fallen some 86 per cent from its pre-crash peak.

Similarly, the go-go market of the 1960s first sold off in 1970 when the Dow plummeted from a high of nearly 1,000 to a low of 631. Investors assumed that this was a nadir and, sure enough, late in 1970, the benchmark index began to climb. The bear market rally of the early 1970s ran for a little more than two years, reaching a climax early in 1973, with the Dow making a new high of 1,071. Many thought that a new bull market had begun. Within weeks, the the crash of 1973-1974 began. When it bottomed, the Dow had sunk to 577 - seven points below where it had traded in 1958.

An entire generation was driven out of the stock market. It would be another eight years before a new bull market began.

The jobs picture is even worse than it

seems

And despite what the experts say, inflation is out there, and

we’re feeling it already.

Bill Fleckenstein, CNBC 15/3 2004

Using the seasonally adjusted total unemployment rate of 5.6% and adding to it "discouraged" workers, the rate grows to 5.9%. Factor in other groups of people who are underutilized in the work force, you can ratchet the number all the way up to 9.6%. And, for the sake of comprehensiveness, if you use the non-seasonally adjusted numbers, that rate would swell to 10.9%. So, those are the numbers, and I'll leave readers to draw their own conclusions.

What's particularly scary is how pathetic job growth has been, despite all the interest-rate cuts (nominal rates are near zero, and real rates are essentially below zero), the two Bush tax cuts and now the refunds from the last cut. Despite it all, we still can't get enough jobs created.

Realräntor/Real Interest rates

The failure of the US economic recovery, now

more than two years old, to produce meaningful job growth has generated much

talk about its political consequences.

It could undermine President

George W. Bush's re-election prospects, and it certainly seems to be

contributing to the national alarm about outsourcing, trade and overseas

investment.

But the bigger concern is that it may be starting to threaten

the strength and even the sustainability of the recovery itself.

Financial

Times editorial 9/3 2004

With last Friday's dismal news from the Labour Department that just 21,000 net new jobs were added in February, total non-farm payrolls remain almost 2.5m below their pre-recession peak. For comparison, in the early 1990s at the same stage of the cycle, in what was also called a jobless recovery, non-farm payrolls had already surpassed their previous peak.

This weakness is, of course, the reflection of the economy's stellar productivity performance; while US employment has remained at a standstill for the past year, gross domestic product is up by more than 5 per cent.

If employment does not begin to show strength soon, consumers are likely to retrench, weakening aggregate demand. To avoid that, either productivity growth must, improbably, collapse, or output must accelerate.

A more plausible gentle slowdown in output per hour would need to be accompanied by stronger demand and output elsewhere.

The American consumer has been surprisingly steadfast for the past three years. Figures last week from the Federal Reserve showed why: household net worth reached an all-time high at the end of last year as modest equity increases were augmented again by gains in housing wealth. But even if the Fed stays on hold for the rest of this year - as looks increasingly likely and sensible - it has scant room to provide the stimulus that lowered mortgage rates and helped raise house prices in the past three years.

The US has had a jobless expansion for more than two years. It will soon start to test the limits of its durability.

Varning för global bubbla

I botten på

problematiken ligger att Fed har hållit styrräntan på en

rekordlåg nivå efter att it-bubblan sprack 2000

Cecilia Skingsley, Dagens Industri 8/3

2004

Berkshire Hathaway, the insurance and

holding company run by legendary investor

Warren Buffett, amassed a

record cash pile of $36bn in 2003 as the world's second-richest man

once

again shied away from rising stock markets

Financial Times 8/3 2004

"Our capital is underutilised now...It's a painful condition to be in - but not as painful as doing something stupid," added Mr Buffett. The chairman's caution has been largely justified in the past, particularly during the technology bubble in 1999, which was the last time that Berkshire shares underperformed against the S&P 500 and the year after its previous cash peak.

Mr Buffett also highlighted a number of risks to the US economy that add to last year's warnings on derivatives, mutual funds and corporate governance.

In particular, he singled out the weak dollar as a cause for concern and revealed that Berkshire Hathaway had $12bn invested in foreign currencies to balance its exposure to the falling greenback. "Prevailing exchange rates will not lead to a material letup in our trade deficit. So whether foreign investors like it or not they will continue to be flooded with dollars," said Mr Buffett. "The consequences of this are anybody's guess. They could, however, be troublesome - and reach, in fact, well beyond currency markets."

Last week, Alan Greenspan was

a study in contradiction.

On Monday, he extolled the virtues of the

levered-up homeowner to a credit union conference. The next day, in a speech to

the Senate Banking Committee, he was singing a different tune altogether.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the giant providers of mortgage capital, he warned,

"are expanding at a pace beyond that consistent with systemic safety," and that

"preventative actions are required sooner, rather than later."

The views and

opinions expressed in Bill Fleckenstein's columns are his own and not

necessarily those of

CNBC on MSN Money - 1/3

2004

The next day, in a speech to the Senate Banking Committee, he was singing a different tune altogether. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the giant providers of mortgage capital, he warned, "are expanding at a pace beyond that consistent with systemic safety," and that "preventative actions are required sooner, rather than later."

For a Federal Reserve chairman who has demonstrated that he couldn't identify reckless behavior if it ran him over, it was rather surprising to hear him chide Fannie and Freddie for their recklessness. (I should state, however, it’s an opinion I tend to share.)

Before quoting from the above, I would just note that Greenspan's latest comments reminded me of a speech he gave on March 6, 2000, which I have dubbed "An Ode to Technology." In the speech, he waxed on about the wonders of technology and how it had brought us a new era and all that other stuff. Folks may not remember that date, but it was four days before the Nasdaq Composite hit its all-time high of 5,048.62.

Despite the recovery over the past year ago, the composite is still down nearly 60% from the March 2000 peak.

This is not the first time Easy Al has been way off. On March 7, 2000, I wrote a column called “Alan Greenspan: Friend or Foe” that chronicled some of his prior quotes, speeches and the like. It includes his Jan. 7, 1973, utterance (right before the recession that ranks as our worst, at least until we get through the one we're in but haven't completed): "It is very rare that you can be as unqualifiedly bullish as you can be now." http://www.fleckensteincapital.com/old_raps/friend_or_foe.htm

Remarks by Chairman Alan Greenspan

The revolution in

information technology

Before the Boston College Conference on the New

Economy, Boston, Massachusetts

March

6, 2000

The fall in real yields

Rising real yields may come as a

nasty shock to the stock market

By Philip Coggan,

Investment Editor FT.com site; Feb 23, 2004

The blissful combination of

higher growth and lower inflation that has characterized the U.S. economy since

last spring is the inverse of stagflation, the nightmare scenario that followed

the oil shock of 1973-74

Still lower inflation is a distinct

possibility.

John Makin AEI 29/1 2004

Since last spring, the United States has experienced the apparent happy paradox of sharply higher growth but lower inflation. However, listening to the persistent complaints about higher U.S. budget deficits and the uneasy murmurs about the need for the Federal Reserve to start tightening monetary policy--not to mention grave concerns about a weaker dollar (another way to boost aggregate demand)--it is easy to see that many economists and policymakers are clueless about recognizing the type of cycle we are in and how to respond to it.

The blissful combination of higher growth and lower inflation that has characterized the U.S. economy since last spring is the inverse of stagflation, the nightmare scenario that followed the oil shock of 1973-74, when higher oil prices produced lower output, lower growth, and higher inflation. The current cycle is fundamentally benign--more output at lower prices--but if policymakers fail to recognize it as such and ignore falling prices because output growth is strong, a global recession could occur.

A little reflection provides a straightforward explanation of the current cycle. The old bugaboo, stagflation, reflects a backward shift of aggregate supply to less output at each price level along a negatively sloped aggregate demand schedule. Output falls, and prices rise. In the inverted circumstance we see today, an outward shift of aggregate supply--that is, more output at each price level-a-long a negatively sloped aggregate demand schedule occurs, and the result is more output at lower prices.

Both types of supply shifts are confusing to policymakers and analysts because most of the time growth and inflation levels are positively correlated, with higher growth tied to higher inflation and lower growth to lower inflation. That is because aggregate demand shifts are typically larger than shifts in aggregate supply. An outward shift in aggregate demand results in a new intersection with a positively sloped aggregate supply schedule at a higher price level and a higher level of output, and a drop in aggregate demand has the opposite effects.

During the second half of 2003, when high levels of U.S. policy stimulus boosted demand growth, U.S. inflation and interest rates actually fell. The Fed's favorite measure of U.S. inflation--the year-over-year core PCE deflator--fell steadily, from 1.8 percent in 2002 to a cycle low of 0.8 percent in November of 2003. Now the core PCE (short for "personal consumption expenditures") deflator at 0.8 percent is below the 1 percent level designated by Fed governor Ben Bernanke as the minimum comfort level. Bernanke pointed this out in his talk before the American Economic Association in early January.

Interest rates on U.S. ten-year notes have been remarkably stable since peaking in August at 4.5 percent, following a sharp sell-off tied to a perceived change in Fed policy with respect to purchases of long-term notes and bonds. In fact, prior to August, two-thirds of the rise in ten-year yields resulted from a rise in expected real yields (based on TIPS pricing), from a low of 1.5 percent early in June to nearly 2.5 percent in August--an extraordinary and unprecedented move in real interest rates.

If there still is aggregate excess capacity in the U.S. economy, as suggested by the concurrence of low real interest rates and falling inflation, what can we expect to see in the future? Still lower inflation is a distinct possibility.

Low interest-rate peril

James

Grant September 27, 2002

Asia will not rethink currencies

soon

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 18/2 2004

Japan and Asian emerging market economies have one thing in common: they are desperate to keep their currencies down against the US dollar. They would far rather lend the US the money with which to buy their exports than endanger their competitiveness or become reliant on fickle foreign finance. Does this behaviour make sense? Is it likely to change soon? The answer to these questions is: Yes and, in all probability, No.

The Europeans, in particular, long for the Asians to share in the adjustment to the weakening US dollar. This passionate desire is not surprising. According to the February Consensus Forecasts, the current account surplus of the Asia-Pacific region was $234bn last year, against only $35bn for the eurozone. This makes it puzzling, at first glance, that it is the euro, not the Asian currencies, that is soaring.

Asian emerging market economies have learnt from the experience of 1997 and 1998 a lesson that is rather different from that drawn by orthodox economists. The latter believe that the crisis showed the danger of adjustable pegs. It would be better, goes the argument, to choose between irrevocably fixed exchange rates (or, better still, dollarisation) and freely floating rates.

The directly affected countries drew a different conclusion. Polonius advised his son to be neither a lender nor a borrower. The Asians decided instead that it was far better to be a lender than a borrower.

The chief explanation for this is what economists have come to call "original sin", by which they mean the reluctance of international capital markets to lend in the currencies of emerging economies. If such economies become substantial net debtors in foreign currency, they become vulnerable to mass bankruptcy or public sector insolvency if their currency tumbles. Yet just such a collapse becomes likely as foreign currency indebtedness grows. The solution then is to prevent the country from becoming a net debtor in the first place.

The conclusion is that Asian exchange-rate policy is perfectly rational. So when might it change? The answer lies in what Prof McKinnon calls "conflicted virtue". As the stock of foreign currency accumulates, speculation on an appreciation rises, making it ever more costly to hold the currency down. In addition, foreigners start complaining about the trade surpluses, arguing that they are the unfair result of currency undervaluation.

Whatever Europeans may desire, the prognosis is that Asia will continue to run huge current account surpluses and interfere in exchange markets. Its governments will not lightly abandon policies that they believe work well for the convenience of any outsiders.

Ronald McKinnon: The East Asian Dollar Standard

http://siepr.stanford.edu/papers/briefs/policybrief_jan04.html

"Det mest sannolika", skriver

han, "är att vi får se ett börsras utan like följt av ett

sammanbrott för dollarn, en händelsekedja som kan tänkas

göra slut på USA:s imperieställning".

Carl Johan

Gardell, SvD Kultur 17/2 2004

Emmanuel Todd - Låtsasimperiet. Om det amerikanska

systemets sönderfall.

(Après l"empire. Essai sur la

décomposition du système américain) Övers: Pär

Svensson 216 S.

Bokförlaget DN. CA 247:-

Under det sista århundradet före vår tideräknings början förvandlades romarriket från en regional stormakt i Italien till ett Medelhavsimperium som sträckte sig från dagens Irak till de brittiska öarna. Inflödet av tributer från erövrade provinser slog ut det italienska näringslivet. Tillverkningsindustrin blomstrade i periferin där efterfrågan stegrades och produktionskostnaderna var låga. Imperiets kärnområden blev ett svart hål - eller en keynesiansk konjunkturstimulator - med en stormrik samhällselit som konsumerade det överskott som den då kända västvärlden producerade. Relativt obetydliga störningar - som krig eller skördekatastrofer - riskerade till slut att utlösa en veritabel statskollaps. Under senromersk tid var det mäktiga imperiet, precis som USA i dag, en koloss på lerfötter.

Ovanstående reflexioner har hämtats från boken Låtsasimperiet, publicerad på franska 2002, som i dagarna kommit ut på svenska. Författare är den franske antropologen, demografen och historikern Emmanuel Todd som sedan 70-talet skrivit flera internationellt uppmärksammade böcker.

---

The power and influence of the United States is being overestimated, claims French historian and demographer Emmanuel Todd. "There will be no American Empire." "The world is too large and dynamic to be controlled by one power." According to Todd, whose 1976 book predicted the fall of the Soviet Union, there is no question: the decline of America the Superpower has already begun.

http://dominionpaper.ca/features/2003/the_conceited_empire.html

---

After the Empire, The Breakdown of the American Order,

Emmanuel Todd

Translated by C. Jon Delogu Foreword by Michael Lind

$29.95 November, 2003 cloth 192 pages ISBN: 0-231-13102-X Columbia University

Press

"A powerful antidote to hysterical exaggeration of American power and potential by American triumphalists and anti-American polemicists alike. A best-seller in Europe, Todd´s book should be read by all thoughtful Americans for its provocative and well-informed analysis of their nation and its prospects." –from the foreword by Michael Lind

"The most effective and most talked about of the new anti-American texts." –Adam Gopnik The New Yorker

http://www.columbia.edu/cu/cup/catalog/data/023113/023113102X.HTM

US government will run up a budget

deficit of nearly $500bn in 2004 - the largest in US history in absolute terms,

5% of GDP

BBC 27/1 2004

Highly recommended - good links

The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office says the US government will run up a budget deficit of nearly $500bn in 2004 - the largest in US history in absolute terms, and, at 5% of GDP, the largest since 1993 as a percentage of the economy.

The budget deficit is now one quarter of total Federal spending, and 80% of the total receipts from Federal income taxes.

It is equal to $1,600 per US citizen this year, and the accumulated deficit over ten years would be nearly $20,000 per person.

"USA har ryckt åt sig ett stort

försprång och har världens mest framgångsrika ekonomi"

Klas

Eklund på SvD:s ledarsida 2000-08-11

SINCE September 11th 2001, it has become obvious to all

that the world is a risky place. Even before that atrocity, the world had

seemed far from safe to many, especially those concerned with business and

finance.

The end of the dotcom craze and the bursting of the stockmarket

bubble had already created huge uncertainty. But those are only the most recent

examples of unexpected events that can make a mockery of people's

plans.

The

Economist Survey 22/1 2004

The dogs of Davos don't bark at the real

dangers

continuing overoptimism about Europe, a Democrat in the White

House, inflation

Anatole Kaletsky, The Times January 22, 2004

This “view from Davos” is certainly a valuable guide, but not quite in the way intended. Rather than pointing to where the world is going in the next 12 months, the annual consensus established in Davos shows what will not happen.

Last year, the message was one of profound gloom — the war in Iraq would engulf the world in years of violence, the global economy would slide into depression and stock- markets would suffer another collapse. In the event, of course, the opposite occurred. Looking back, a similar pattern emerges over the years: the view from Davos is usually a contrary indicator, at least of the short-term trends. In 2002, Davos expected another terrorist attack even worse than that of September 11. In 2001, the consensus anticipated a Thirties-style depression, triggered by the collapse of technology shares. In 1999, there was the global peril of the millennium bug.

The view from Davos is not always gloomy, although the rich and powerful are often very insecure about the future, presumably because their happiness is so bound up with their power and their fortunes, which can quickly evaporate. In 2000, the consensus was manically enthusiastic, celebrating the limitless wealth created by the internet. In 1998, there was equally misguided jubilation about the launch of the euro and the new economic superpower it would create.

My aim is not to suggest that the participants at Davos are purblind or foolish, although it is true that success as a businessman or politician requires such fanatical concentration on a single company or political project that it is easy to miss the wood for the trees.

This, however, is not the main reason why the Davos consensus is so often misguided. There is another problem — the very fact that these elites are so powerful and so rich. Between them, they control most of the world’s economic output and almost all of its military might. If they all focus on one opportunity or one danger, then the chances are that this particular opportunity has already been largely exploited or this danger warded off.

It is when no consensus exists among the world’s rich and powerful — for example, on climate change or Israeli expansionism, or the Saudi support for Islamic terror — that the dangers fester and grow. When a subject is not even mentioned at Davos it has maximum capacity to surprise and therefore to change the world, for good or ill.

Last year, I was struck by three huge economic issues which Davos completely ignored.

As I wrote here last year, the rise of the euro and its devastating effect on Europe hardly even got a mention.

I was also amazed that “nobody even bothered to talk about the possibility that Wall Street would rebound” rather than collapsing.

Finally, it surprised me that Davos paid so little attention to the rise of the Asian consumer and the shift in global growth leadership from America to Asia, especially China. In the event, all three of these issues turned out to be crucial for understanding the world in 2003.

So today it seems worth asking: what are the Davos dogs not barking at this year?

The easiest one to spot is the continuing overoptimism about Europe. While last year’s indifference to exchange rates has given way to a recognition that the euro is now dangerously overvalued, nobody seems to be drawing the obvious conclusion. The European economy will remain completely stagnant this year because the sharpest rise of the euro has been very recent and will not have its full impact until the end of 2004 and beyond. Unless the euro falls very soon and very abruptly, Europe will have no chance of sharing in this year’s global economic recovery. Geopolitically this means that the EU, like Japan in the 1990s, will be condemned to political paralysis and irrelevance for much of the decade ahead. The Davos elite’s outdated view of Europe as potential superpower looks like a big mistake.

A second case of rearview thinking concerns the US economy and the presidential election. Nobody in Davos seems seriously to believe that America might oust President Bush and put a Democrat in the White House. The surprise result in the Iowa Democratic Party caucuses has increased the chances of Wesley Clark, who I believe is the most plausible Democrat contender. Yet the confidence in an easy Bush victory seems to extend even to people who personally hate him. This is hard to reconcile with the opinion polls, which show the race as a dead heat. Perhaps the faith in Bush simply reflects the near-universal optimism about the US economy this year.

But what Davos ignores is that America’s economic problem in the years ahead will probably be too much growth, not too little. A booming and over-stimulated US economy will present the next occupant of the White House with a daunting challenge: to clean up the mess made by Bush not only in Iraq but also in the US Government’s budget. The only way to do this will be to create a national consensus for unpopular measures to raise taxes. But will any politician be able to do this, especially after what is likely to be one of the dirtiest election campaigns in US history?

The third, and most important, subject that is not being discussed at Davos is inflation. Will 2004 be the year when the world moves from price stability into an era of accelerating inflation reminiscent of the 1960s? In America, the combination of very loose money, rapidly growing budget deficits, devaluation, protectionism and military spending has always been a recipe for inflation in the past. Rising oil, gold and commodity prices all point in this direction, as does the global boom in property prices and the new bubble in stockmarkets now being created by the US Federal Reserve.

Yet despite all these warning signs, the Davos consensus sees economic weakness, not inflation, as the main economic peril in the year ahead. This is exactly the situation in which inflation is likely to start. The people supposed to control inflation — central bankers, politicians and bond investors — are part of the global elite represented at Davos. So if Davos ignores inflation, the same will be true of the Federal Reserve and the other anti-inflationary vigilantes. Thus nothing will be done to pre-empt an inflationary spiral before it takes off.

The same is true of the other dangers overlooked at Davos. If the Davos elite is caught napping by European stagnation or by US political turmoil or by the rising euro, the central banks and governments and other guardians of global stability will also be taken unawares and will fail to ward off these dangers. That is why the Davos consensus is genuinely important — and why it so often turns out to be wrong.

Stephen Roach, chief economist at Morgan Stanley, is

more pessimistic.

By keeping interest rates unnaturally low and greatly

increasing fiscal spending, U.S. policymakers have fueled the creation of a

series of bubbles in asset markets

International Herald Tribune 22/1

2004

Roach has been consistently bearish as the global economy weathered the dot-com stock collapse three years ago, followed by a recession in the United States and elsewhere and a less-than-scintillating recovery over the last year.

By keeping interest rates unnaturally low and greatly increasing fiscal spending, he said, U.S. policymakers have fueled the creation of a series of bubbles in asset markets. A new one might be forming now in technology stocks, he added.

By opening the fiscal and monetary taps, Washington policymakers have also inflated the current account deficit, the broadest measure of trade in goods and services. The current account shortfall has been cited by many economists as a cause of the falling dollar; the United States requires net inflows of close to $2 billion a day just to finance the current account, because it imports far more goods and services than it exports.

Greed, fraud, credulity and the bull

market

By Philip Coggan Financial Times; Oct 23, 2003

BULL! A

HISTORY OF THE BOOM, 1982-1999

What drove the breakneck market and what

every investor needs to know about financial cycles

By Maggie Mahar

Harper Business, £16.85

The bull market ofthe 1980s and 1990s was one of the most powerful in history. It incorpo rated all the classic features of abubble: easy credit, mass participation, fraud and a naive belief in a "new era" that would justify the euphoria.

Much analysis has focused on the final excess, the dotcom bubble and its idiocies. But in the history of the bull market, this was just the cherry on the cake. There was a lot more to the rise in share prices than profitless e-tailers.

Maggie Mahar, one-time English professor at Yale turned financial journalist, has attempted a more comprehensive look at the period. It is an entertaining romp, complete with pen portraits of the heroes - bears such as Gail Dudack and David Tice - and villains. The latter are clearly more numerous, ranging from the anchors of the financial TV network CNBC to the senators who in 1993 blocked an accounting standard that aimed to spell out the true cost of executive options. On this evidence at least, we must hope that Senator Joseph Lieberman does not win the Democratic nomination for president. For anyone who was involved in the bull market, the book does not provide any great new revelations. It is the incidental detail that keeps the story motoring, such as the abusive phone calls received by internet analyst Henry Blodget when whenever he dared question the credentials of one of his client's favoured stocks. Blodget, made a scapegoat for the sins of the analysts' community, emerges as a fairly sympathetic figure, a man clearly out of his depth.

All the main issues are covered, from dodgy accounting, the explosion in mutual funds, the belief in the new economy and the cheerleading role played by investment bank analysts. But if there is a flaw in the book, it is that it focuses almost entirely on the US and on the personalities in that market. While the US was undoubtedly the home of the great bull market, a proper history of the phenomenon would have to include Europe, where in the late 1990s, the equity culture appeared to sweep the continent.

Risk management for the masses

Mar 20th 2003 From

The Economist print edition

Robert Shiller is professor of

economics at the International Centre for Finance, Yale University, and the

author of “Irrational Exuberance” (Princeton University Press,

2000).

His new book, “The New Financial Order: Risk in the 21st Century” (to be published by Princeton University Press on April 2nd; $29.95 and £19.95), on which this article is based, lays out a vision for the future of finance, insurance and social welfare.

Warren Buffett, the influential

investor, warned derivatives were “financial weapons of mass

destruction” and that they were “potentially lethal” to the

economic system.

In his letter to shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway,

Mr Buffett said he and Charlie Munger, the investment and insurance

company’s vice chairman, viewed derivatives and derivative trading as

“time bombs”.

Financial

Times 4/3 2003

The boom that did not bust

By John Plender

Published: February 6 2003 21:02

Greenspan's fight

Low interest rates is

not enough

By Martin Wolf

Financial Times, November 12 2002

America

is not in danger of deflation

Glenn Hubbard

The writer is chairman

of the US president's council of economic advisers

Financial Times, October

9 2002 22:19

Behovet av ett nytt ekonomiskt

tänkande

/ finansiella bubblor/Mattias LundbäckSvD Inblick

2002-10-04

Bubble, bubble default trouble

By

John Plender

Financial Times, October 3 2002 20:15

RE: Very important article - as always with John

Plender

BBC 12 September, 2002

US economic guru Alan Greenspan has warned

lawmakers that their inability to balance the federal budget threatens the

country's economic stability. Mr Greenspan, chairman of the US Federal Reserve,

urged Congress and the administration of President George W Bush to restrain

the urge to cut taxes while raising levels of public spending. ...more

Vilken

bubbla spricker härnäst? Det amerikanska undret

Mats

Johansson 1/9 2002

USAs sparare flyr aktiefonder

DI 2002-08-28

Uttagen ur aktiefonder nådde en ny rekordnivå under juli månad i USA, då investerare plockade ut omkring 50 miljarder dollar netto.

Senast i september i fjol, efter terrorattackerna i USA, rapporterades rekordstora uttag ur aktiefonderna. De uppgick nettouttagen till 30 miljarder dollar. Det kan också jämföras med juni månad i år då uttagen var cirka 18 miljarder dollar netto.

There may be a knighthood

for Greenspan in stage-managing a bubble, but there's nothing but pain for

everyone if we tell lies to each other to keep it going.

By Bill

Fleckenstein CNBC website 2002-08-19

John Plender

Financial Times; Jul 15, 2002

So you think this bear market is rough? It is positively limp-wristed

when compared with the depths of the mid-1970s.

Watching out for the great bear

Jul 4th

2002 From The Economist

The dilemma facing policymakers was neatly encapsulated by the European Central Bank (ECB), whose main governing body met on July 4th to decide what to do about interest rates.

The ECB continues to be worried about inflation: it has often failed to hit its inflation target (no bad thing say those economists who believe the target is too tight), and Wim Duisenberg, the bank’s president, admitted that “the risks to price stability remain tilted to the upside.” Yet the ECB left rates unchanged because, said Mr Duisenberg “the uncertainties were too large to come to a decisive decision.”

Since, in theory, at least—and in public—the ECB insists that its only target is inflation (and not, unlike America’s Federal Reserve, economic growth as well), the principal uncertainty for Mr Duisenberg and his colleagues is the possible inflationary impact of recent currency swings.

By themselves, falling stockmarkets do not usually cause recessions. It is now generally accepted that the blame for the Great Depression in 1930s America does not lie with the Wall Street crash of 1929 but the unreasonably tight monetary policy which followed it.

Illusory profits cloud USA Inc

Sunday, 30 June, 2002

Nearly a year ago, Graham Turner warned that the US economy was driven by a huge bubble of artificially inflated profits. Writing for BBC News Online, he explains why the Enron, WorldCom and Xerox scandals are just the tip of the iceberg.

Den starka dollarn är bara en bubbla - den enda

som inte spruckit än.

USA:s ekonomi växer troligen

långsammare än omvärldens de närmaste åren. Risken

för ett nytt bakslag, en så kallad "double dip", är över

40 procent.

Det budskapet levererade Steve Roach, chefsekonom på den

amerikanska investmentbanken Morgan Stanley, när han gästade Sverige

i förra veckan. "

Vi har levt över våra tillgångar och

kommit undan med det", säger han. "Jag är här för att tacka

er å hela det amerikanska folkets vägnar, för att ni pumpade in

pengar i USA och hjälpte oss att blåsa upp en

spekulationsbubbla."

Mer av Roach

The surprising fact is not that /US stock/ markets

have fallen, but that they remain so overvalued.

Martin Wolf: The bubble

will keep deflating

Financial Times 2002-06-19

Terrible twins?

Economic parallels between

America and Japan

America's economy looks awfully like Japan's after its

bubble burst

Jun 13th 2002 From The Economist print edition

The recovery myths

The world economy is coping

with the aftermath of two huge asset-price bubbles: the Japanese of the 1980s;

and the US-led worldwide bubble of the second half of the 1990s.

Adjustment

to the end of the first is not yet over. Adjustment to the end of the second

has, contrary to conventional wisdom, hardly begun.

By Martin Wolf,

Financial Times June 11 2002

- Det exklusiva svenska fondbolaget Brummer & Partners har

värvat en riktig pessimist som USA-chef, eller "bear" (björn) som det

heter på Wall Street.

DI 2002-06-10

"Jag vet att jag har det ryktet, men jag vill hellre kalla mig realist", säger Douglas "Doug" Cliggott.

Sin pessimistiska syn på aktiemarknaden har Cliggott som sagt tagit med sig från J P Morgan.

"Kurserna är fortfarande höga, P/e-talen för de breda aktieindexen i USA är extremt höga", säger han.

"Förväntningarna om vinsttillväxt är uppblåsta och under de nästkommande två till fem månaderna är det hög sannolikhet för att förväntningarna kommer att skruvas ned. Det sätter press på börsen."

Capitalism and its troubles

SURVEY:

INTERNATIONAL FINANCE

May 16th 2002 From The Economist print edition

CAPITALISM has had a rotten time lately. Not as rotten as in 1917, when those revolutionary shots in St Petersburg launched a form of anti-capitalism that ended (except in Cuba and North Korea) only just over a decade ago.

Nor, with luck, as rotten as in 1929, when a stockmarket crash on Wall Street set off the global Great Depression.

But rotten, nonetheless. Nobody knows for sure yet, but 2001 might come to be seen as the year when two decades of mostly unbroken progress for capitalism gave way to something more ambiguous and uncertain.

Analysts sense day of reckoning for dollar:

A fall

in capital inflows to the US has alarm bells ringing

Christopher Swann

Financial Times; Apr 27, 2002

The key problem for the US currency is that investors do not need to sell US assets for the dollar to fall. All that is necessary is that they fail to buy. The bloated US current account deficit, running at about 4 per cent of gross domestic product, means that the US needs to attract a net inflow of around Dollars 1.5bn (Pounds 1.04bn) every day in order to stop the dollar falling. The latest figures from the US Treasury provide strong indications that capital inflows are finally drying up. In January the net inflow into US equities and fixed income was just Dollars 9.5bn. This is weak even compared with the Dollars 17.8bn the US attracted in September.

What glitters ain't gold

The Economist April 11th 2002

There are two theories about Wall Street's role in the bubble years of the new economy. Either investment analysts were swept up, like everybody else, in the prospect of extraordinary gains in efficiency that the Internet would bring, so justifying ever higher share prices.

Or Wall Street saw a golden chance to peddle dirt.

New York's attorney-general, Eliot Spitzer, is a promoter of the second theory. On April 8th he delivered an affidavit to the state's supreme court that paints Merrill Lynch's share-buying recommendations for Internet companies during 2000 as little more than a pretext to stuff gullible buyers with the shares of rotten businesses. (Big customers, meanwhile, were whispered the truth.)

Why Greenspan allowed

irrational exuberance

Gerard Baker, Financial Times, March 07 2002

Riksgäldskontorets ledning och förre

börschefen varnar:

"Banker vilseleder aktiespararna"

(realränta)

DN Debatt 2002-03-19

"Hög produktivitet rättfärdigar

inte p/e-tal"

DI 2002-03-11

2 067 miljarder kronor.

Så mycket har

Stockholms börsen minskat i värde sedan IT-bubblan sprack den 6 mars

för knappt två år sedan. Summan är drygt 100 miljarder

kronor högre än Sveriges BNP för 2001.

Den motsvarar

nuvärdet på sex Ericsson eller 20 Telia. Märkligt nog är

det just Ericsson som stått för två tredjedelar av detta ras.

Sedan den 6 mars 2000 har telejätten dalat i värde från 1 790

miljarder kronor till 360 miljarder kronor i dag.

The houses that saved the world

Mar 28th 2002

From The Economist

By the end of 2001, American debt service burdens relative

to disposable income

were at forty-year highs

John H. Makin,

American Enterprise Institute, March 2002

There is still worth in value

Philip Coggan

Financial Times, January 26 2002

The doom-mongers

The Economist 2002-01-24

America sails serenely through a perfect storm

Gerard Baker, Financial Times, Jan 24 2002

The 1990s’ Boom Went Bust. What’s Next?

Milton Friedman

Wall Street Journal 2002-01-22

USA i kraschläge

DI:s Cecilia Skingsley

2002-01-21

Hoping for a recovery

Financial Times

editorial, January 19 2002

The Future of Money and of Monetary Policy

Fed Governor Laurence H.

Meyer December 5, 2001

http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2001/20011205/default.htm

Chairman

Alan Greenspan January 11, 2002

Although the quantitative magnitude and

precise timing of the wealth effect remain uncertain, the steep decline in

stock prices since March 2000 has, no doubt, curbed the growth of household

spending. Although stock prices recently have retraced a portion of their

earlier losses, the restraining effects from the net decline in equity values

presumably have not, as yet, fully played out.

Future wealth effects will

depend importantly on whether corporate earnings improve to the extent

currently embedded in share prices.

Alan Greenspan om "irrational exuberance"

A world without easy money

Martin Wolf,

Financial Times, Dec 11 2001 19:33:18 GMT

A poor defence for

share prices

Martin Wolf Financtial Times, Oct 23 2001

It’s time to come back down to earth

By

Philip Coggan, Financial Times, October 5 2001

The troubles with technical trends

Barry

Riley, Financial Times, October 4 2001 19:35

Summer of discontent

Barry Riley, Financial

Times, September 28 2001

Global Recession—Longer and

Deeper

Stephen Roach, Morgan Stanley

2001-09-25

As The Implosion Begins . . .?

Prospects

and Policies for the U.S. Economy: A Strategic View1 Wynne Godley and Alex

Izurieta Jerome Levy Economics Institute, July 2001 (rev. August 2, 2001)

The great bear - Stock markets have been in decline

since early 2000.

Philip Coggan, Financial Times, September 21 2001

This is now one of the worst bear markets in history. In early trading on

Friday, the Dow Jones Industrial Average had fallen 31 per cent from its

January 2000 peak, one of the worst 10 declines the US market has experienced

since the first world war.

Augusti kommer före september

Rolf

Englund i mail 2001-09-20

Jeff Madrick: Will the Market Crash?

The New

York Review of Books, Cover Date: August 10, 2000

Different Times, but the 1990s Do Resemble the

1920s

By Robert J. Samuelson The Washington Post

International

Herald Tribune, Thursday, April 23, 1998

Två tredjedelar av hela

börsvärdet på

Stockholmsbörsen försvann på

två och ett halvt år

DI-ledare 30/12 2002

År 2002 uppenbarades att vi just har varit med om en av historiens största finansbubblor. Och Sverige drabbades hårdast, två tredjedelar av hela börsvärdet på Stockholmsbörsen försvann på två och ett halvt år.

Det behövs en uppgång på 200 procent för att komma tillbaka till nivån från mars 2000 något som kan ta decennier. Att Frankfurt ligger nästan lika illa till är en klen tröst.

Bara två av den moderna historiens finanskriser har varit värre, New York 1929 och Tokyo 1989. I det första fallet tog det 25 år för börsindex att komma tillbaka och i det andra fallet pågår raset fortfarande efter 13 år. Tokyoindex ligger i dag 73 procent under 1989. Börsbubblor är inget att ta lätt på.

Fyra av det sena 1900-talets största hjältar i svenskt näringsliv - Percy Barnevik, Lars Ramqvist, Jan Stenbeck och Jan Carendi - har fått se sina livsverk radikalt omvärderade.

Wallenberg, den finansfamilj som dominerat scenen i Sverige i 70 år, är nu på sin höjd den främsta bland jämlikar. Betyget över Peter Wallenbergs insats får skrivas ned.

Investors förlorade pengar överskuggas av de 100 miljarder kronor som statens AP-fonder lyckades bränna på kort tid genom att kasta in den statliga sparreserven i pyspunkan.

Det sena 1990-talets it-entreprenörer liknar mest - så här efteråt - bondfångare. En del var naiva och andra smarta. Frågan är i vilken av kategorierna namn som Mandators Lars O Petterson, Icon Medialabs Johan Staël von Holstein, Sprays Jonas Svensson, Mirror Images Alexander Wik, Ledstiernans Jan Carlzon, Connectas Christer Jacobsson, Framfabs Jonas Birgersson och Emerging Technologies Kjell Spångberg ska sorteras. Det som förenar är att it-bubblan löste deras försörjningsproblem.

Socialdemokratin, som tog över hegemonin i svensk politik efter Kreugerkraschen, har nu hjälpt till att blåsa upp två nya bubblor, först en i fastigheter och finans år 1989 och därefter den senaste i it och telekom år 2000.

The boom that did not bust

By

John Plender

Published: February 6 2003 21:02

In the developed world it appears that financial crises no longer derail economies. Even in Japan, which has experienced four years of price deflation and where the banking system has been in crisis for over a decade, the output loss has been minor. And now the collapse of a phenomenal stock market bubble in the US has defied historical precedent by spawning only a modest recession and no banking crisis at all.

There are many possible explanations for the failure of this financial dog to bark. Much more of the risk-taking was happening outside the banking system than in the 1980s. Banks appear better capitalised as a result of the Basle capital regime. Most important, policymakers in the US have been acutely aware of the risks of deflation and swift in their monetary and fiscal response to the bursting of the bubble. Thursday's cut in UK interest rates likewise suggests that the risks in UK policy are not being taken on the side of deflation.

So now the politicians and central bankers are intensively managing the business cycle, can we stop worrying about the impact of financial instability on economic growth? Not in the emerging markets, where financial crises in Asia, Latin America and Russia have inflicted devastating losses of output and employment. And there is one important snag in the developed world, especially in the English-speaking economies.

The existence of a monetary and fiscal safety net creates moral hazard. That is, companies, financial institutions and private individuals engage in balance sheet adventuring - an evocative phrase used by the economist Hyman Minsky, whose thinking on financial instability and the business cycle is particularly relevant in the post-bubble world.

Financial crises serve a purpose. In cycles that have been characterised by debt-financed and unremunerative over-investment, the discipline of bankruptcy ensures that debt is written down to realistic values and capacity is brought into line with demand to pave the way for an upturn. But the adjustment is painful.

If financial crises are eliminated, the business cycle is extended. Asset prices continue to rise, generating wealth effects that encourage people to run down savings and borrow on the strength of the rising value of their collateral. As the Montreal-based Bank Credit Analyst points out, the failure to correct balance sheet excesses in the downturn means that each new US expansion begins from progressively lower levels of liquidity.

US household debt has gone from less than 40 per cent of gross domestic product in 1960 to close to 80 per cent in 2002. The comparable rise for the non-financial corporate sector has been from 26 per cent to 46 per cent. The greater the balance sheet excesses, the more painful the corrective process will ultimately be. So with each new cycle, say the BCA editors, the stakes become higher, pushing the economy closer to a deflationary end-point. An end is inescapable since debt cannot rise faster than incomes for ever.