Home - Index - Carl Bildt 1992 - Cataclysm - News

TIPS in a Rising Interest Rate Environment

multnomahgroup

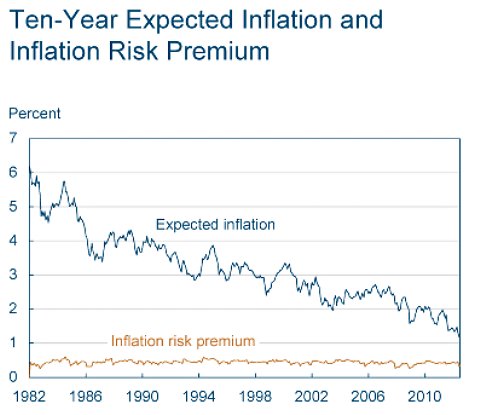

Core US inflation is rising and now exceeds 2 per cent.

The 10-year inflation break-even — the rate of inflation at which inflation-linked and fixed income bonds would pay the same, and hence the implicit forecast rate of inflation — is rising.

It is the highest in four years, close to 2.2 per cent; low in historical terms, but above the Fed’s target.

FT 21 April 2018

The 10-year Treasury yield was on a menacing rising trend earlier this year. This broke through the long established downward trend in yields that had lasted since the early-1980s. But that rise in yields has stalled, below 3 per cent.

Surge in ‘real yields’ could spell danger for stocks

https://englundmacro.blogspot.com/2018/10/surge-in-real-yields-could-spell-danger.html

US inflation-linked funds hit in sell-off

Pimco’s Real Return Asset Fund has lost investors 16.1 per cent of their capital in 2013,

ranking it as the worst performer in the bond mutual fund universe

Financial Times, June 25, 2013

US bond funds promising to shield investors from the effects of rising prices by buying inflation-linked securities have fallen victim to the worst trade in fixed income markets.

The dire performance for the 203 funds investing in inflation-linked securities, down 7 per cent on average this year, according to Lipper, highlights the volatile nature of what is still a relatively undeveloped market.

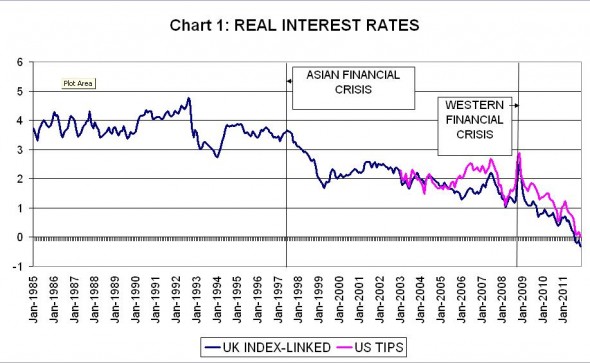

Index-linked bonds currently present the most remarkable features.

For most of their history, such “linkers” have yielded between 2pc and 4pc after inflation, that is, in real terms.

Recently, however, real yields have been negative.

That’s right, investors have willingly held them at yields which are bound to lose money in real terms.

And investors even have to pay tax on the interest.

Roger Bootle, Telegraph 9 June 2013

The debt crisis

Can it be inflated away?

Buttonwood May 22nd 2013

http://www.economist.com/blogs/buttonwood/2013/05/debt-crisis

It’s hard to see why the Fed should raise rates until unemployment falls a lot and/or inflation surges,

and there’s no hint in the data that anything like that is going to happen for years to come.

Paul Krugman, New York Times 9 May 2013

Yields in the index linked market remain largely negative at present, which feels distinctly bubble-like

Yet they have been driven down by the perfectly rational fear that extreme monetary measures could lead to inflation

and that inflation could be part of the solution to the developed world’s overhang of public sector debt.

Perhaps this should not really be called a bubble because the protection offered by index linked is invaluable

if you fear the worst, even if the security offers a negative real return.

John Plender, FT, January 29, 2013

"I think the greatest bubble that is about to burst is the 10-year and longer Treasury,

because the idea that inflation is gone forever and for all time, and therefore these artificially low rates can last, is silly,"

the president of W.H. Ross & Co. said in an interview

Jeff Cox CNBC.com Senior Writer 21 March 2012

Investors pour money into funds that protect against inflation

FT 5 January 2018

Funds that buy inflation-protected bonds took in a fresh $743m for the week ending January 3

The UK has seen record levels of demand from investors

for its latest inflation-linked bond syndication.

FT 7 November 2017

Order books for Tuesday’s £3bn, 30-year paper closed at £23.7bn,

making the new 2048 gilt eight times oversubscribed

The Big Reversal: Inflation And Higher Interest Rates Are Coming Our Way

Charles Hugh Smith/Seeking Alpha, 7 November 2017

Apparently unbeknownst to conventional economists, trends eventually reverse or give way to new trends.

My view is that once this tsunami of new debt-based currency hits the real-world economy, inflation will move a lot higher a lot faster than most pundits believe is possible.

Real interest rates aren’t particularly low

FT Alphaville 17 August 2017

The current real yield on 10-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities is about half of one percentage point

while the current real interest rate on 3-month Treasury bills is about 1.3 percentage points below that.

This spread is narrower than it’s been over the past few years, and far narrower than the post-1980 average.

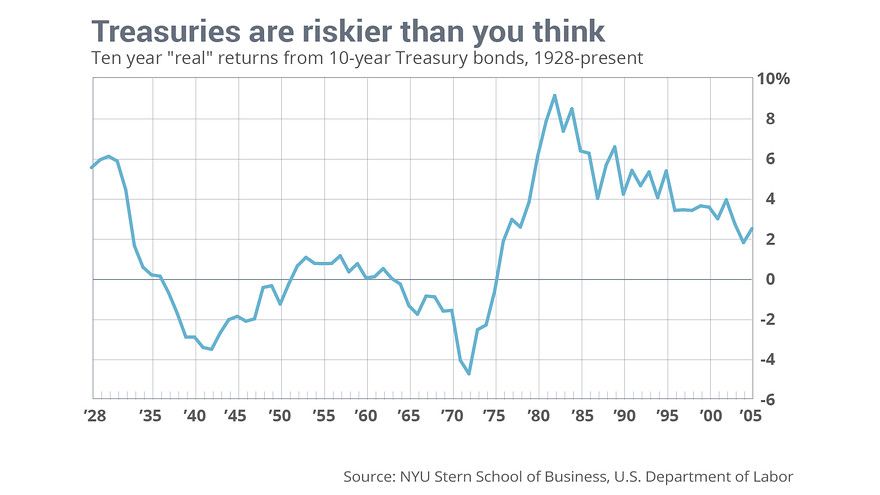

The performance enjoyed in the recent past probably won’t repeat.

Residential real estate, not equity, has been the best long-run investment over the course of modern history.

–“The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870–2015” by Jorda, Knoll, Kuvshinov, Schularick, and Taylor

For the longest time I railed on about the dangers of irresponsible monetary policies. It got so bad that on my ski trips, my pals banned me from talking about Greenspan’s reckless behaviour.

Yet today, I have come around to the idea that the debt problem is so pervasive, there is only way one forward - inflate.

We are going to end up there anyway, so let’s just inflate away the burden and restart with a system that prevents this from ever happening again.

Kevin Muir via The Macro Tourist blog, zerohedge, 7 April 2017

As traders we need to concern ourselves about what is, instead of, what should be.

Trump’s election has almost certainly ended the 35-year trend of disinflation and declining rates that began in 1981,

and that has been the dominant influence on economic conditions and asset prices worldwide.

But investors and policymakers don’t believe it yet.

Anatole Kaletsky, Project Syndicate 30 January 2017

In today's auction by the U.S. government of $13 billion in 10-year Treasury

Inflation-Protected Securities demand was so great that primary dealers were left with about 16 percent of the bonds,

the lowest on record in data going back to 2003.

Robert Burgess, Bloomberg 19 January 2017 with nice charts

Flood of money into inflation protected bonds

FT 9 November 2016

Peter Schaffrik at RBC invites investors to play a game of spot the difference in the US Treasury market.

In the bond sell-offs of 2013 and 2015, the difference between the nominal yield on 10-year US Treasurys and the real yield (which strips out the rate of inflation) was minimal, meaning market expectations of inflation were almost non-existent. Today that gap is expansive.

Fears about the damage wrought by inflation have propelled a flood of money into inflation protected bonds, with more than $1bn poured into the funds in the week to October 26 — the second largest weekly total on record, according to data from EPFR.

Now, some strategists and investors think that the linkers

— inflation-linked government bonds — trade is back on

FT 20 October 2016

“Many clients I meet worry that the biggest macro risk on the horizon is another financial crisis,”

But the bigger threat is accelerating inflation

Torsten Slok, Deutsche Bank’s chief international economist.

MarketWatch 12 May 2016

Increasingly hysterical calls for negative interest rates, helicopter money and the like look premature

The era of zero interest rates has a lot longer to run yet.

Real rates of return, traditionally in the 2.5pc to 3pc range, are virtually impossible to come by

Jeremy Warner, 6 Feb 2016

These securities might be the only safe haven left

The yields on some inflation-protected Treasury bonds have doubled since the spring

MarketWatch Oct 19, 2015

The Great Yield Divergence

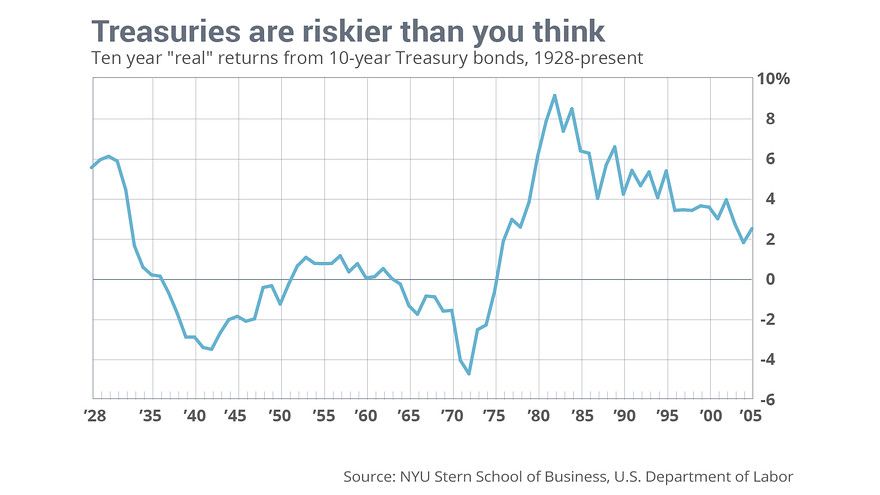

When a former Bank of England deputy governor gives a presentation entitled "Are Low Interest Rates Natural?" to a extraordinarily high-powered audience of academics and monetary policymakers, you can bet he will come up with some great charts.

Charlie Bean's historical analysis of long-term real and nominal yields in the UK is amazing:

300 years of UK nominal and real long-term yields

Coppoloa Comment 27 September 2015

Such divergence between nominal and real rates suggests that there is a continual drain of resources from workers to rentiers, from young to old and from poor to rich. This shows itself as rising indebtedness among the young and poor, and increasing fragility of the global financial system.

It cannot possibly be sustainable.

Why a house-price bubble means trouble

Contrast today’s low-inflation economies with the high inflation of the 1970s and 1980s.

Back then, paying off your mortgage was a sprint:

After five years of that, inflation had eroded the value of the debt and mortgage repayments shrank dramatically in real terms.

Today, a mortgage is a marathon.

Interest rates are low, so repayments seem affordable. Yet with inflation low and wages stagnant, they’ll never become more affordable.

Tim Harford, FT 21 November 2014

Expectations for inflation over the next five years,

as measured by comparing yields on Treasury inflation protected securities and those of nominal Treasury bonds,

have approached their double low of June 2013 and December 2011.

FT 23 September 2014

A drop in the so-called break-even rate for the next five years towards 1.62 per cent from 2.1 per cent earlier this summer,

reflects the influence of a stronger dollar and lower commodity prices that have reduced inflationary pressure in recent months.

Speaking on Monday, William Dudley, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York said:

“We really need the economy to run a little hot, at least for some period of time” to get inflation back to the central bank’s objective.

US inflation over the next five years, 1.62 per cent - Ha

How can anyone pretend to know what is happening in five years?

Rolf Englund blog 2014-09-24

The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

John Maynard Keynes, (attributed)

Real rate bonds

Here is how Bob /Robert Hetzel/describes his great idea in his book “The Monetary Policy of the Federal Reserve”:

The Market Monetarist 22 June 2014

In February 1990, Matched-maturity securities half of which would be nominal and half indexed to the price level.

The yield difference, which would measure expected inflation,

would be a nominal anchor provided that the Fed committed to stabilizing it

With a market measure of expected inflation, monetary policy seen by markets as inflationary would immediately trigger an alarm even if inflation were slow to respond.

I mentioned my proposal to Milton Friedman, who encouraged me to write a Wall Street Journal op-ed piece, which became Hetzel (1991).”

The Monetary Policy of the Federal Reserve

Mr Draghi this time seeks to end the threat of deflation. Will he be equally successful?

Experience suggests that only the brave would bet against him.

Yet to succeed twice would be quite a remarkable achievement.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times June 6, 2014

At present the world’s high propensity to save is not matched by a desire to invest.

High-income economies have had ultra-cheap money for more than five years. Japan has lived with it for almost 20.

The highest interest rate charged by any of the four most important central banks in the high-income economies is 0.5 per cent at the Bank of England.

Martin Wolf, FT May 6, 2014

These unprecedented policies are needed because of the chronic deficiency of global aggregate demand.

Before the wave of post-2007 crises hit the world economy, this deficiency was met by unsustainable credit booms in a number of economies.

In the case of pension funds, reduced long-term yields are particularly unwelcome because they both lower returns and raise the present value of future liabilities. Many life insurers might be forced out of business if these rates persist. This is a crisis on a long fuse.

Keynes even had a phrase for it – the “euthanasia of the rentier”.

In a world of abundant savings, the available returns ought to be low; this is a consequence of market forces to which central banks are responding.

Keynes, Krugman, Secular Stagnation and The Death of the Rentiers

Izabella Kaminska, FT Alphaville, 23 January 2014

Why are real interest rates so low? And will they stay this low for long?

If they do – as it seems they might – the implications will be profound:

good for debtors, bad for creditors and above all, worrying for the vigour of global demand.

Martin Wolf, FT April 29, 2014

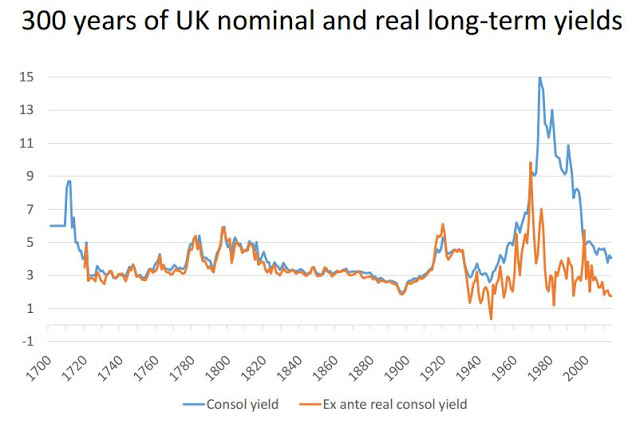

The International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook includes a fascinating chapter on global real interest rates.

Here are its most significant findings

Strikingly, the 10-year real rate of interest was 4 per cent in the mid-1990s, 2 per cent in the 2000s, before the crisis, and close to zero thereafter.

High quality global journalism requires investment. Please share this article with others using the link below, do not cut & paste the article. See our Ts&Cs and Copyright Policy for more detail. Email ftsales.support@ft.com to buy additional rights. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/c8e5d2a2-cebe-11e3-8e62-00144feabdc0.html#ixzz30OfpuAsQ really big question in such a world is whether conventional inflation targets might be too low, because they do not give enough room for real interest rates to fall as far below zero as necessary.

Keynes, Krugman, Secular Stagnation and The Death of the Rentiers

Izabella Kaminska, FT Alphaville, 23 January 2014

IMF published a fascinating chapter in its latest World Economic Outlook (WEO) on global real interest rates,

showing that the global real rate has fallen from about 6 per cent in the early 1980s to about zero today.

Gavyn Davies, FT blog April 6, 2014

Highly recommended

imf.org/external/Pubs/ft/weo/2014/01/pdf/text.pdf

The IMF says that the main reason for the drop in real rates in the 1980s and 1990s is obvious: the easing in monetary policy that occurred after the 1979-82 Volcker tightening.

*

Kommentar av Rolf Englund:

USA:s tidigare centralbankschef Paul Volcker är mest känd för att ha blivit tillsatt av Ronald Reagan för att få ner inflationen,

vilket lyckades genom en hård åtramning med recession som följd.

Det ryktet kvarlever med märklig kraft.

Men Kaletsky menar att det var Paul Volcker som ledde återgången till "demand management".

- In the United States, the return to demand management began as early as the summer of 1982, when a three-year recession and the bankruptcy of the Mexican government persuaded the Fed that its experiment with monetarism had gone too far.

Läs mer här

*

After 2000, the IMF identifies other forces, each of which is associated with a different school of economic thinking:

A drop in investment demand in the advanced economies. This is very similar to the secular stagnation hypothesis, recently advanced by Larry Summers and Paul Krugman.

The global economy could be heading for years of "sub-par growth", according to the head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Christine Lagarde warned that without "brave action" the world could fall into a "low growth trap".

Ms Lagarde also urged more action to tackle low inflation in the eurozone.

Christine Lagarde, managing director of the IMF, warned of several obstacles to a sustained recovery

including job-killing “low-flation” in the eurozone

Financial Times 2 April 2014

Lagarde 2014 och Englund 2010 om deflation och inflation

Rolf Englund blog 2014-01-15

- With central bankers afraid to even mention the word “deflation”, Ms Lagarde’s remarks make her the first high profile policy maker to warn that extremely low inflation in rich countries could result in the kind of falling prices that have dogged Japan’s economy for almost two decades. FT 2014-01-15

Riktiga karlar är inte rädda för lite inflation

Kan inflationen bli för hög? Ja, det vet ju alla.

Kan inflationen bli för låg? Javisst, för litet och för mycket skämmer allt,

som jag tror det var Curt Nicolin som sade. Rolf Englund 2010-02-19

Riktiga karlar är inte rädda för lite inflation

Rolf Englund blog den 19 februari 2010

Over the past 12 months, inflation throughout much of the world has dropped like a stone,

ending up at levels wholly unanticipated at the end of 2012.

If Japan’s problems partly stemmed from a failure to spot the onset of deflation,

might it be that policy makers in the west could be sleepwalking into the very same problem?

Stephen King, Financial Times 13 January 2014

Rather than faster growth leading to higher inflation, lower inflation eventually leads to slower growth.

In between, the credit system is slowly asphyxiated.

This was exactly Japan’s experience in the mid-1990s.

The large drop in inflation last year elsewhere in the world may only be a lagged response to earlier economic weakness but,

if that is so obvious now, why was it that no one managed to forecast the drop a year ago?

Why stagnation might prove to be the new normal

In the past decade, before the crisis, bubbles and loose credit were only sufficient to drive moderate growth

Even if the economy accelerates next year, this provides no assurance that it is capable of sustained growth at normal real interest rates.

Lawrence Summers, December 15, 2013

Negative yield of 0.75 per cent

New low for US inflation-protected debt

Financial Times, September 20, 2012

Treasury Inflation Protected Securities, or Tips, came at a negative yield of 0.75 per cent, the lowest on record.

Investors accepted the lowest yields ever for 10-year inflation debt in a US Treasury auction, amid rising expectations the Federal Reserve’s latest move to aid the economy will lead to higher consumer prices.

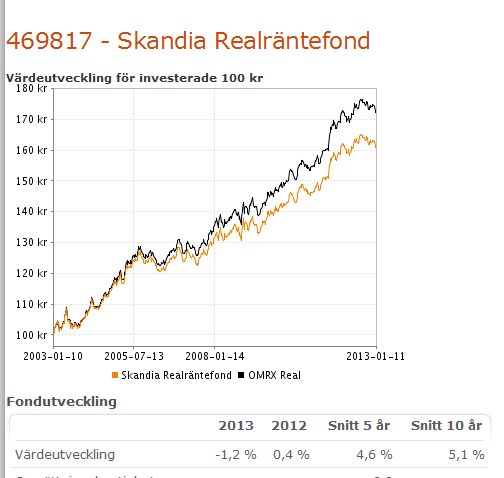

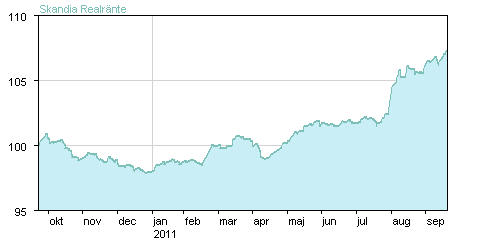

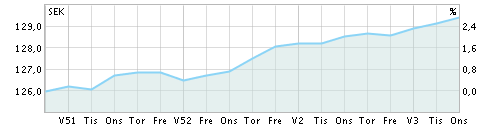

Skandia Realräntefond 143,39 SEK 20/9 2012

10y TIPS

David Glasner is unhappy with Allan Meltzer, who wrote an absurd op-ed in the WSJ in which Meltzer,

among other things, just makes stuff up — claiming that markets are signaling fear of inflation when they are in fact doing no such thing.

Paul Krugman, July 14, 2012

You might think that the complete failure of the predicted inflation takeoff to materialize would at least give him pause. But no: his dogmatism is completely unshaken.

Actually, has even one prominent economist or economic prognosticator who got everything wrong admitted it, or shown even a hint of humility?

Has anyone perhaps hinted that the policy recommendations he was making might not be right, given the total failure of events to go the way he predicted?

I can’t think of one.

För 20 år sedan inledde Ronald Reagan en våg av skattesänkningar i västvärlden. När USA sänkte sina skatter skärptes trycket på andra att följa efter.

Under en period blundade många i Europa och en rad ekonomer (däribland jag själv) hävdade att Reaganomics var ett oansvarigt tänkande.

Men vi hade fel. USA har ryckt åt sig ett stort försprång och har världens mest framgångsrika ekonomi.

Klas Eklund på SvD:s ledarsida 2000-08-11

What is the real rate of interest telling us?

The real interest rate on US and UK government debt is currently near to zero

Martin Wolf, FT, 19 March 19 2012

This is a remarkable fact. True, real interest rates were negative in the 1970s. But it is extremely unlikely that anybody bought bonds expecting this to be the case.

Now, however, the position is quite different. Both of these governments sell index-linked debt that delivers zero real returns.

That is a demonstration of the fact that the world has a huge “savings glut”, an idea famously proposed by Ben Bernanke in 2005 (“The Global Saving Glut and the U.S, Current Account Deficit”, March 10 2005,). In

Indeed, since savings must equal investment at the global level, it is only by its price – the rate of interest – that one can assess whether such a glut exists.

The coincidence between the fall in the real rate of interest in 1997-99 and the beginning of the bull market in housing in the US and UK is indeed remarkable. The collapse in real interest rates also helped exaggerate an already impressive bull market in equities, which topped out, at extraordinarily overvalued levels, in 2000.

Bond yields have been extraordinarily low in the developed world in recent times because the economies have been stuck in, or very near, a liquidity trap.

Longer term government interest rates have remained positive, but at 1.9 per cent they were very close to the territory which Keynes warned about,

in which the future yield on the bonds did not compensate holders for the risk of capital loss if economic circumstances changed.

Gavyn Davies, FT, 18 March 2012

USA

To be able to borrow money at -2.0%/year real and invest it in useful things is a very, very good business to be in

Brad DeLong, 11 March 2012

The breakeven rate on Sweden’s 10-year inflation-linked bonds shows

investors expect annual inflation of 1.55 percent over the next decade

“When breakevens have been at these levels, traditionally it has been a buy,”

Bloomberg, Jan 23, 2012

Martin Tallroth, an interest rate strategist at Swedbank AB in Stockholm, said in an interview.

“Index-linked bonds look cheap relative to the nominal bonds.”

How the west cut its debts

The crucial issue is that during that period, the state engineered a situation where the yields on government bonds were kept slightly below the prevailing rate of inflation for many years.

Gillian Tett, FT, December 22, 2011

What Reinhart and Sbrancia argue is that if you want to understand how the west cut its debts during the last great bout of deleveraging, namely after the second world war, then do not just focus on austerity or growth

Riktiga karlar är inte rädda för lite inflation

Rolf Englund blog, 19 februari 2010

Next Bubble Is Forming: U.S. Government Bonds

NS&I pulls inflation-linked savings certificates

More than 500,000 savers have bought NS&I index-linked savings certificates to beat low interest rates and rising inflation.

DT 7 September 2011

The announcement is the latest blow to savers who have seen their income plummet at a time when most savings accounts fail to offer any real rate of return once inflation and tax are taken into account.

NS&I is tasked with raising a fixed amount for the Government coffers each year

There is no other investment which guarantees an annual return of RPI inflation plus 0.5% tax free over the coming five years, so the return of inflation proof bonds will be welcomed by many

According to the Treasury’s website, the effective yield (not counting the inflation adjustment) was MINUS 0.825 %,

(-0.825%) not 0.825%.

Investors are so desperate for inflation protection, they’re will to PAY nearly an extra percent over par UP FRONT to buy it.

Wall Street Journal 18 Augusti 2011

Inflation har historiskt varit ett sätt att minska tunga skuldbördor.

Metoden kan bli aktuell igen som ett sätt att bekämpa skuldkrisen. Storbritannien har redan börjat.

Viktor Munkhammar, DI 2 okt 2011

Sverige och många andra länder hade periodvis tvåsiffriga inflationstal och negativa realräntor under 1970- och 1980-talen. Den höga och ojämna prisökningstakten hade många nackdelar. Men för dem med stora skulder fanns en stor fördel: Inflationen minskade snabbt skuldbördan.

För att räkna ut den verkliga avkastning som tillexempel en köpare av statsobligationer får på sina utlånade pengar brukar man tala om realränta, det vill säga räntan justerad för inflation.

I USA är den ettåriga realräntan idag minus 3 procent, i Storbritannien minus 4 procent, i Tyskland minus 1 procent.

Även i Sverige är realräntan negativ

Andreas Cervenka, SvD Näringsliv 20 maj 2011

Förlorare på denna makroekonomiska motsvarighet till skimming är framförallt pensionärer, som via olika fonder är stora investerare i statsobligationer. Men också sparare med pengar på vanliga bankkonton kan känna sig blåsta. För ett land som kämpar för att bli av med stora skulder är minusräntor däremot rena rama mirakelkuren. Och den har använts förr, med framgång

Cui bono? The banks, of course

På sikt hotar en ny världsomspännande inflationsvåg, skriver han.

Om boken Peer Steinbrück, tidigare Tysklands finansminister, Unterm Strich

Rolf Gustavsson, SvD 6 november 2010

Kritiken mot Handelsbanken Liv har uppstått mot bakgrund av en generell kris bland livbolagen, som är hårt ansatta av rådande marknadsförhållanden.

Under många år har bankens försäkringskunder garanterats räntor på mellan 3 och 5 procent, vilket bolaget inte kan leverera med dagens marknadsräntor.

Att skriva på det här sättet, utan att lyfta fram att kunderna trots dagens finansiella klimat sitter med garanterade räntor på upp till 5 procent, är helt groteskt

SvD Näringsliv, 7 december 2012

– Det värsta är att man lyfter kunderna ur traditionella försäkringar där banken har hög risk och liten lönsamhet, och in i fondförsäkringar där banken har låg risk och hög intjäning. Det är win-win för banken, och lose-lose för kunden, fortsätter Magnus Gewert.

Rekordlåga räntor under lång tid betyder lägre pension. Samtidigt har många pensionsbolag utlovat en viss garanterad återbäringsränta.

I Sverige finns enligt Finansinspektionen 1 900 miljarder kronor placerade hos livförsäkringsbolag och i pensionskassor.

1 300 miljarder av dessa är kopplade till en garanterad ränta på i genomsnitt 3,5 procent. Består lågräntevärlden kan vissa, framförallt mindre bolag, få svårt att uppfylla sina åtaganden enligt FI.

Andreas Cervenka, e24 13/2 2011

Det är inte bara livbolagen som har problem med sina pensionslöften. Det tickar även en pensionsbomb i börsbolagen.

Det handlar om miljardbelopp som företagen inom drygt ett år måste täcka med eget kapital.

Patricia Hedelius, SvD Näringsliv 30 september 2011

Kenneth Rogoff, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund and now a professor at Harvard University,

Given the low growth, he says, inflation above central banks’ targets could be helpful:

“A bit of inflation is by far the lesser evil compared with even lower growth.

Five per cent inflation for 2 to 3 years is not the end of the world. There are even some benefits.”

Financial Times 13 may 2011

The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

"I don't know who's buying 30-year fixed debt.

I don't understand TIPS (Treasury Inflation Protected Securities) that are projecting 30 years of benign inflation,"

Ray Dalio, founder & CIO of the hedge fund Bridgewater Associates, 3 Mar 2011

"When you get to China with a 5 percent rate and a 15 percent nominal growth rate, it's a no brainer," he said.

"You don't want to lend; you want to borrow. And that creates a fuel in a bubble."

Bridgewater Associates is the world's largest hedge fund, with $8.9 billion under management.

It has returned more to its investors than Google, Amazon, Yahoo and eBay combined.

Today’s rock-bottom yields, however, have less to do with disinflation and more to do with providing fuel for an asset-based economy that promotes unsustainable wealth creation and a false confidence in perpetual capital gains.

Bill Gross, Pimco, February 2011

Investors accepted a yield of minus 0.55 per cent on $10bn of Treasury Inflation Protected Securities

– or Tips – which compensate holders if the consumer price index rises.

Financial Times 26/10 2010

Expectations for inflation over the next five years – based on comparing Treasury yields and those for Tips – have risen as high as 1.75 per cent this month, up from 1.13 per cent in August

TIPs are the best

Posted by Izabella Kaminska on Aug 13 18:18. on FT Alphaville

There’s been lots of pondering about the negative five-year Treasury inflation-protected (Tips) rate,

but here’s one explanation that strikes us as extremely sensible.Tips are the best.

In the event of deflation, they perform just as well as conventional bonds because it’s not their coupons that are adjusted for inflation but their principals.

Ten-year Treasury yields fell this month to their lowest levels since the dark days of January 2009.

TIPS are at similarly historical levels, lowest since the government started selling them in 1997.

A low yield means demand is high for TIPS, which offer investors additional annual returns to make up for the rate of inflation.

The gap, or breakeven, between the two yields implies what investors expect inflation to be.

WSJ 25/10 2010

Interest rates near zero risk fanning asset bubbles or propping up inefficient companies, say Raghuram G. Rajan and William White, former head of the Bank for International Settlements’ monetary and economic department.

After Europe’s debt crisis recedes, Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke should start increasing his benchmark rate by as much as 2 percentage points so it’s no longer negative in real terms, Rajan says.

Bloomberg 23 August 2010

The real interest rate on 5-year inflation-protected securities is now negative.

In other words, prospects for other investments are so poor that some investors prefer a safe asset that doesn’t quite keep up with inflation.

The invisible bond vigilantes continue their invisible attack: nominal 10-year bonds at 2.71%.

Paul Krugman 11 August 2010

The British government has just stopped the sale of index-linked national savings certificates.

These paid the rate of inflation plus 1% for five years, with returns being tax-free.

Buttonwood, The Economist July 20th 2010

Over the long run, a government should leap at the chance to fund itself at 1% real; that ought to be less than Britain's GDP growth rate.

A cynic would look at the decision and say "Aha! The government either believes that inflation will stay high, or is pursuing a deliberate policy of inflating away its debt. It would rather issue bonds at a nominal 3% fixed than pay 1% real."

A 1% real return is not generous historically. Savers should get some real after-tax return or why would they save?

(Buttonwood should declare an interest; I am such a saver. But the change does not affect the value of my existing portfolio, only stops me from buying more.)

The certificates look so good in relative terms because the government/Bank of England are punishing savers with low rates, high inflation and high taxes.

Full textSavings products linked to the inflation rate have been withdrawn from the market by National Savings and Investments after proving too popular.

BBC 19 July 2010

Index-linked savings certificates were withdrawn from sale by NS&I at the start of the day because sales "far exceeded" the level anticipated.

Some savers have been attracted to products with interest linked to inflation because other rates are low.

Arun Motianey, author of the book "SuperCycles" and director Roubini's:

The global economy is entering a next "supercycle" phase

that will generate inflation necessary for recovery

CNBC 10 Mar 2010

"It's going to be inflation everywhere and it's going to happen really through the weakness of the US dollar," he said.

Jag har länge propagerat för realräntepapper - i USA benämnda TIPS - och de senaste tre åren tycks det ha varit en god placering.

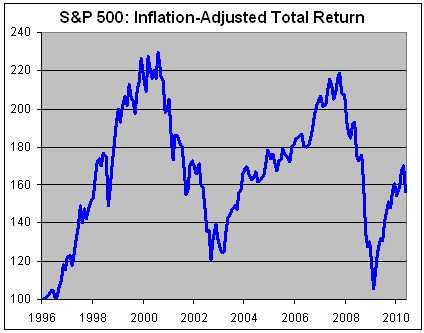

Inflation Adjusted S&P500 June 2, 2010, Tim Iacono

Even long-term rates are low — the real interest rate on

10-year bonds is below 1.5 percent.

Paul Krugman NYT March 5, 2010

Suppose that we add debt equal to 100 percent of GDP, which is much more than currently projected;

servicing that debt should cost only 1.4 percent of GDP, or 7 percent of federal spending.

Why should that be intolerable?

So what’s the problem? Confidence.

If bond investors start to lose confidence in a country’s eventual willingness to run even the small primary surpluses needed to service a large debt, they’ll demand higher rates, which requires much larger primary surpluses, and you can go into a death spiral.

What we’re doing now is moving in the wrong direction,

with real interest rates rising even as the nominal rate remains at zero.

Paul Krugman February 19, 2010

Larry Summers, Paul Krugman, Gavyn Davies

Utan bubblor kollapsar ekonomin

Andreas Cervenka, SvD Näringsliv 19 november 2013

I anledning av Summers

Det kanske är så att utan bubblor och snabb kreditexpansion skulle vi inte haft de tillväxttal vi kommit att vänja oss vid.

Det tycks finnas en underliggande och långsiktig stagnation som dolts av excesserna de senaste två decennierna.

Peter Wolodarski, DN, 1 december 2013

Allt detta talar för att de flesta västländer kan ha gått in i en ny fas av ”sekulär stagnation”; ett fenomen som ekonomer oroade sig för på 1930-talet.

"We should not dismiss the possibility, raised by Larry Summers

that we may need negative real rates for a long time"

I interpret this as IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard saying,

as clearly and straightforwardly as his office allows him to,

that in his judgment the 2% per year inflation target is past its sell-by date and rotted,

and that the North Atlantic economies need to move to a 4% per year inflation target

in order to reduce the risk of another 1932, or another 2010.

Brad DeLong, November 20, 2013

Harvard economist Larry Summers created a stir earlier this month when he suggested that

the world economy may be entering a period of “secular stagnation,”

where aggregate demand fails to recover and sustain growth on anything like the pre-crisis trajectory.

Darrell Delamaide, MarketWatch, 20 November 2013

Did inflation targeting fail?

Central banks have mostly escaped blame for the crisis.

How can it have gone so wrong?

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, May 5, 2009

The orthodoxy on inflation is certainly shifting.

The best policy may well be to talk tough about inflation while keeping interest rates low for as long as possible.

The Economist print March 11th 2010

The anxiety about indebtedness makes inflation seem all the more appealing. Spending in rich countries, such as America and Britain, will flounder as long as households look to pay down the debts they acquired to buy expensive homes.

A burst of unanticipated inflation that was not expected to last would be a salve to the most troubled rich economies, but it is not something that can be easily engineered. Even so, how much regret would even the most hawkish central banker feel if inflation rose above 2% for a while without making bond investors nervous?

The best policy may well be to talk tough about inflation while keeping interest rates low for as long as possible.

It’s all been a polite, rather academic discussion so far,

which is odd given that commodities are rampant, asset prices are bubbling, and inflation targets about to be or already breached in Asia and the UK.

Perhaps, behind the scenes, a change of heart among central bankers has already happened.

FT Lex March 19 2010

Olivier Blanchard, the IMF’s chief economist called for several bold innovations.

Central banks should raise their inflation targets—perhaps to 4% from the standard 2% or so.

The Economist print Feb 18th 2010

The logic is seductive.

Because inflation and interest rates were low when the crisis hit, central banks had little room to cut rates to cushion the economic blow.

Once their policy rates were down to almost zero, the world’s big central banks had to turn to untested tools, such as quantitative easing. Politicians had to boost enfeebled monetary policy by loosening their budgets generously.

Had inflation and interest rates been higher, policymakers would have had more room to cut rates. That gain, Mr Blanchard argues, might outweigh the small distortions from modestly higher inflation, especially if countries reformed their tax systems to make them inflation-neutral.

Mr Blanchard might be wrong. He may be understating the costs of higher inflation.

Comment by Rolf Englund:

Yes, he might. But he is after all the IMF’s chief economist.....

Was inflation sown in The Great Moderation?

Riktiga karlar är inte rädda för lite inflation

Rolf Englund blog 19/2 2010

The Case For Higher Inflation

Olivier Blanchard, currently the chief economist at the IMF,

conclusion, central banks have been setting their inflation targets too low

I’m not that surprised that Olivier should think that; I am, however, somewhat surprised that the IMF is letting him say that under its auspices. In any case, I very much agree.

Paul Krugman, Febr 13 2010

there’s another case for a higher inflation rate — an argument made most forcefully by Akerlof, Dickens, and Perry (pdf). It goes like this: even in the long run, it’s really, really hard to cut nominal wages. Yet when you have very low inflation, getting relative wages right would require that a significant number of workers take wage cuts.

Or to put it a bit differently, the long-run Phillips curve isn’t vertical at very low inflation rates.

The main argument for a higher inflation target was put forward by Olivier Blanchard and his colleagues in 2010:

a higher inflation target makes it easier to cut real (inflation-adjusted) rates deeper still should the economy require it.

Since then, a higher inflation target has won steadily more adherents.

Martin Sandbu, FT 4 January 2017

The gap between yields on Treasuries and so-called TIPS due in 10 years closed above 2.25 percentage points last week, the longest stretch since August 2008.

That’s the low end of the range in the five years before Lehman Brothers collapsed,

and shows traders expect inflation, not deflation in coming months

Bloomberg Dec. 21 2009

Bernanke has cited tame inflation expectations for keeping the target interest rate for overnight loans between banks at a record low range of zero to 0.25 percent and the unprecedented stimulus that prevented more bank failures during the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Now, TIPS show the improving economy may change sentiment and spark further losses in bonds. Yields on the benchmark 10-year Treasury note hit a four-month high of 3.62 percent last week.

Inflation Tips

Worries about the size of America’s budget deficit and fears about the potential politicisation of the Federal Reserve are rising.

There is a danger that higher headline inflation will be misread, even as rising energy costs sap demand.

The Economist print 12/11 2009

The market for Treasury Inflation Protected Securities shows traders expect inflation over the next 10 years to average 1.96 percent,

which is 0.74 percentage points less than the past decade’s average

Bloomberg, August 11 0009

The U.S. Treasury Department plans to ramp up sales of inflation-protected bonds

China, the largest holder of U.S. government debt, is among investors that have indicated they want to buy more of the securities

Also: Link to nice slideshow about the Biggest Holders of US Gov't Debt, such as Luxembourg, Russia, Brazil,

Caribbean Banking Centers (Bahamas, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Netherlands Antilles, Panama and the British Virgin Islands),

Oil Exporters, Japan, China (Mainland)and Federal Reserve and US Intragovernmental Holdings (That’s right, the biggest holder of US government debt is the United States itself. The Federal Reserve system of banks and other US intragovernmental holdings account for a stunning $4.806 trillion in US Treasury debt.

CNBC/Reuters 5 Aug 2009

China’s central bank warned that its counterparts in developed nations face difficult choices

as monetary easing threatens to cause “severe” inflation and exchange-rate volatility.

“Failure to manage the degree of easing may lead to concerns about mid- and long-term inflation and exchange-rate stability,”

the People’s Bank of China said in a quarterly monetary policy report, posted on its Web site today.

Bloomberg August 5 2009

China, the owner of $801.5 billion of Treasuries, pressed the U.S. at a summit in Washington last month for economic polices to protect the dollar’s value.

Alan Greenspan's tragic mistake

negative real interest rates from 2002 into 2005

It was a painful spectacle to watch.

Wall Street Journal, editorial, October 24, 2008

The original bubble was in housing prices and mortgage-related assets,

which the Federal Reserve helped to create with its negative real interest rates from 2002 into 2005.

This was Alan Greenspan's tragic mistake, not that the former Fed chief will acknowledge it.

Bond Bubble Trouble?

If you have not yet read about the ominous U.S. Treasury bubble (which has been around for awhile),

here is recent a recap:

Brady Willett January 15, 2009

I'd say you got to buy TIPS.

You want inflation protection, and the value of TIPS is near historic

Bill Gross Forbes 6/1 1009

TIPS or inflation-protected securities can benefit

2½% real yields cannot possibly be maintained unless deflation as opposed to inflation becomes the odds-on favourite.

What bond investors know as “breakeven inflation rates” are currently signaling a future where the US CPI averages -1% for the next 10 years.

Possible, but not likely.

Bill Gross January 2009

What I hear more and more, both from bankers and from economists, is that the only way to end our financial crisis is through inflation.

Their argument is that high inflation would reduce the real level of debt, allowing indebted households and banks to deleverage faster and with less pain.

The advocates of such a strategy are not marginal and cranky academics. They include some of the most influential US economists.

Wolfgang Münchau, Financial Times, May 24 2009

/Nominal/ rates on three-month bills turned negative on Dec. 9 for the first time.

The same day, the U.S. sold $30 billion of four-week bills at a /nominal/ zero percent rate.

Bloomberg Dec. 15 2008

Jean-Claude Trichet, president of the European Central Bank, this week gave warning about the mistakes of the 1970s, when inflation was let loose at huge cost to growth.

the average world real interest rate is negative.

The Economist print May 22nd 2008

Why Greenspan does not bear most of the blame

The US is in no way exceptional for the level of residential investment.

Somewhat to my surprise, the share of residential investment in UK gross domestic product has been much the same as in the US.

very low long-term real interest rates

Martin Wolf FT April 8 2008

Yields on five-year Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities fell below zero

on speculation that inflation will quicken as the U.S. economy slows.

Yields on the securities, known as TIPS, dropped to minus 0.036 percent

nakedcapitalism March 4, 2008

Soaring commodity prices, rising headline inflation and weakening economic growth: for those whose memories stretch back to the 1970s, this combination brings painful memories. It reminds them of the mistakes made by the central banks that accommodated the upsurge in inflationary expectations rather than contained them. Inflation was finally brought back under control in the early 1980s. But the costs of letting it escape were huge.

Could we be making the same mistakes again?

Martin Wolf, FT March 4 2008

As Richard Fisher, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas noted in a speech delivered in London on Tuesday: “Since the January federal open market committee meeting, longer-term rates, including those on fixed mortgages, have risen rather than followed the federal fund rates downward.” In such circumstances, aggressive monetary policy may have weak, even perverse, effects on the real economy.

In the US today, inflation expectations are on a knife edge. As I noted last week, the expectations shown in the relation between inflation-indexed treasuries (TIPS) and conventional bonds appear to be quite well contained. But the Cleveland Fed offers a “liquidity adjusted series”, which allows for the desire to hold more liquid assets in a period of financial stress. On this measure, expected inflation is soaring (see chart). The Fed’s position is now uncomfortable. The assumption that it can cut rates without fear of the consequences is wrong.

As of this writing the annual earnings yield on the value-weighted S&P composite index is 5.53%. This is a wedge of 3.22% per year when compared to

the annual yield on 10-year Treasury inflation-protected bonds of 2.31%.

Bradford DeLong February 28, 2008

Who gives a damn about inflation?

Now that the age of moderation has ended, we are returning to Phillips curve-type discussion.

rising inflation is the most painless way out of a debt crisis

Wolfgang Münchau blog 31.01.2008

Krugman on monetary transmission channels

My guess remains that the US and UK will try to inflate themselves out of their troubles.

Wolfgang Munchau (Portal)

The US economy is leading the way, having already entered a stagflationary phase.

Such an environment is poisonous for financial assets.

During such periods, investors are best served keeping most of their allocations in cash and inflation-linked securities.

Tim Bond, head of asset allocation for Barclays Capital 6/12 2007

How did we get here?

To make a long story short: The process was started by money printing in America to bail out the last bubble.

Bill Fleckenstein, CNBC 4/6 2007

That induced money printing in much of the world because so many countries had linked their currencies to the dollar. More importantly, the very regions that were primed to grow -- think Asia, India and the Middle East -- exploded, in no small part, thanks to money printing. Thus, America's housing boom kept our economy growing. Growth in the other parts of the world I just mentioned, together with the attendant commodities boom, conspired to create the worldwide growth (and inflation) that we have experienced.

A lot of what's transpired has been a function of absurdly low interest rates, given the level of inflation around the world, and the collapse in risk premiums, aided by ratings-agency alchemy, which has allowed debt -- from moderately risky to total garbage -- to be spun into high-quality credit structures. In other words, the debt markets have acted as unindicted co-conspirators in the frenzy.

Bostadspriserna är högre än vad som är långsiktigt fundamentalt motiverat och kommer därför att falla.

Enligt BKN:s bedömning är felprissättningen på småhus ca 20 procent.

Bostadspriserna kan falla än mer, om dagens låga realränta stiger.

Statens Bostadskreditnämnd, 28/11 2008

Pengarna är för billiga

Gunnar Örn, DI 2007-05-29

Bland dem som hyllar marknadsekonomi och fri prisbildning har det konstigt nog blivit högsta visdom att det viktigaste priset av alla inte ska sättas ute på marknaden, utan av politiker och byråkrater. I dag är det världens centralbanker som har det avgörande inflytandet över hur högt priset på pengar ska vara. Något som förklarar marknadens extrema fokusering på uttalanden av centralbankschefer som Ben Bernanke i USA, Jean-Claude Trichet i eurozonen, Toshihiko Fukui i Japan, Mervyn King i Storbritannien och Stefan Ingves i Sverige.

Varför är räntan i dag bara hälften så hög som den var på toppen av den förra högkonjunkturen?

Senast var det den västliga samarbetsorganisationen OECD som ställde frågan.

"Realräntorna är ovanligt låga för att vara i det här skedet av konjunkturcykeln", konstaterar OECD-ekonomerna i sin senaste översikt av världens finansmarknader.

"Det öppnar enorma arbitragemöjligheter att låna till låg ränta och köpa tillgångar som ger högre avkastning."

Enligt OECD har vi alltså en fortsatt börsuppgång framför oss. Risken är bara att företagen hinner skuldsätta sig för mycket under resans gång, något som ökar riskerna för framtida krascher.

Den reala räntan går att mäta i priserna på så kallade realobligationer, alltså skuldsedlar som ger en garanterad ränta ovanpå inflationen. Då kan man se att den är mindre än hälften så hög som i förra högkonjunkturen.

I Sverige låg den reala räntan över 4 procent när it-boomen var som värst. I dag är realräntan mindre än 2 procent.

OECD skyller de konstlat låga obligationsräntorna på Kina och andra asiatiska länder. Världen badar i likviditet som en följd av att dessa länder försöker fixera priset på pengar, menar organisationen.

En gyllene regel i ekonomisk teori är att den reala räntan på lång sikt ska vara lika hög som den reala tillväxten i ekonomin.

I USA har realräntan fallit från 4,7 procent i slutet av 1990-talet till 2,7 procent under första kvartalet i år.

A slump was averted partly by very low world long-term real interest rates and partly by the “dissaving” of the US, the UK and other English-speaking countries.

The burden of supporting the world economy can hardly rest indefinitely on the shoulders of Anglo-American shoppers and home owners.

Samuel Brittan 11/5 2007

I believe US stocks are now very attractive for investors.

5 per cent real return on stocks still yields a 3 per cent premium over inflation-indexed bonds

Jeremy Siegel, FT, 26/4 2007

Kudlow doomster???

Caveat Emptor

by Lawrence Kudlow

Inflation-linked bond spreads have been widening, another excess-money signal.

I don’t want to take the inflation threat too far, but...

Kudlow's Money Politic$, 23/3 2007

See also: The Next Bubble - House prices

Over the long-run, the “neutral” stance of monetary policy (also known as the equilibrium real federal funds rate) should be closely related to the potential growth rate of GDP.

Chart 2 shows that the historical “spread” between the real federal funds rate and real GDP growth has been systematically mean reverting.

Paul McCulley and Saumil Parikh, November 2006

This excess of savings over investment in the rest of the world is not the result of high US or global real interest rates. On the contrary, real interest rates are astonishingly low.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times September 27 2006

In a few years, the low bond yields of recent years will look like an anomaly rather than the norm.

Globalisation is more likely to push real interest rates and inflation higher than lower in the next few years.

Joachim Fels, FT, 21/9 2006

The writer is managing director and chief global fixed income economist at Morgan Stanley

Yes, long-term interest rates have been exceptionally low in recent years. Yet this is unlikely to have been caused by a savings glut, but rather by a global liquidity glut that is now receding.

A better explanation for depressed long-term interest rates is that central banks cut short-term interest rates to extremely low levels during the equity bear market of 2000-2003 and the following deflation scare and thus flooded the financial system with excess liquidity.

So why hasn’t IT happened yet?

Thus far the Fed has succeeded in playing Fire Chief and kept pouring

liquidity into the system. But the Fed CAN NOT keep the money and credit spigots wide open indefinitely:

All they are doing is delaying the inevitable, not curing it.

Aubie Baltin 20/9 2006

Real interest rates in the past few years have remained lower for longer than at any other time during the past half-century.

Despite recent tightening by central banks, average real short-term rates and bond yields in the developed economies are still well below normal levels. Most commentators have concluded that a new era of cheaper money has arrived.

The Economist print edition 14/9 2006

As Lawrence Summers, former US Treasury secretary, noted in a recent lecture on India: “There is one striking fact about the global economy that belies a predominantly American explanation for the pattern of global capital flows: real interest rates globally are low, not high.

Why should we remain concerned about global imbalances? The answer is that they are undesirable, cannot continue indefinitely and the longer they last, the bigger and more painful the adjustment will be.

What is undesirable ought to change. What is unsustainable will change. What is dangerous must change.

Yet, if the world is to avoid a serious recession, adjustment must start in the surplus countries.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times 29/3 2006

Inflation-protected bonds, or TIPS, seem like the perfect hedge against rising prices

A securities vehicle with a guaranteed face value and protection against inflation. That's an appealing combination for fixed income investors facing an inflationary environment.

Marc Gerstein, Director of investment research, Reuters.com, 30/5 2006

Assume the CPI-U rises 1% in the first six months after issuance of a TIPS with a 2.75% coupon. At that time, the face value of the security will have been adjusted up to $1,010 and the first semi-annual interest payment will be $13.89 ($1,010 times 2.75%, divided by two to reflect interest for half a year).

These escalations can add up nicely in a prolonged period of high inflation. At the end of the day, combining all the interest received with the higher maturity payoff produce an average annual percentage return of 2.75% plus the average annual inflation rate (a "real" return of 2.75% per year).

But there are several catches. The federal tax status of the interest payments is obvious.

Once the 30-year bond is back it will almost certainly complete the inversion of the long end of the yield curve.

It means that the bond market appears to be betting on a recession.

Jennifer Hughes, Financial Times, 9/2 2006

Bond Market Bubble?

On Tuesday, January 18, the yield on fifty-year inflation-protected U.K. government bonds (what the British call “indexed-linked gilts”) dropped to 0.38 percent, about one-seventh the historical average of just over 2.6 percent for such debt instruments.

John H. Makin, January 31, 2006

A yield drop from 1 percent to 0.38 percent on a fifty-year bond corresponds to a 30 percent rise in its price over a period of just three months. That is an annual return of over 100 percent, much higher than the 13 percent annual increase in U.S. house prices at midyear and the 20 to 30 percent gains seen in the stock market before the March 2000 crash.

The asset bubble has spread to long-term government bonds, especially those with inflation protection. What is going on here?

The price that investors are willing to pay for long-term, riskless income streams has risen to unprecedented levels worldwide. More broadly, U.S. real ten-year yields are extraordinarily low by historical standards. Real yields on long-term bonds in Europe are even lower. These observations constitute the bond market “conundrum” referred to by Alan Greenspan and explained by incoming Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke as the consequence of a global savings glut.

Using data going back to 1870 economic historians have estimated the long-run real rate of interest, after allowing for inflation, to be about 3 per cent.

On Wednesday, fund managers were buying 50-year index-linked gilts on a real yield of less than half a per cent.

John Plender, Financial Times, January 20 2006

Given the tendency of markets to revert to the mean, a casual observer might conclude that the professionals have taken leave of their senses. In fact, the behaviour is rational.

The snag is that what is rational for the individual fund has irrational systemic consequences. Bubbles occur when asset prices lose touch with fundamental values. That is precisely what is happening in the UK index-linked gilts market. As more pension funds adopt liability matching, risk aversion reaches epic proportions and scarcity in the market causes prices to rocket.

Refinancing could prick the index-linked bubble, although it will take a long time before real yields revert to the mean. As for conventional bonds, the pussy cat bond market means that fund managers are placing monumental faith in the ability of central bankers to protect the value of money and preserve their independence from high spending governments.

“it’s different this time”

Because the U.S. economy has evolved into a highly levered finance-based economy, it stands to our reason that this modern day version is more sensitive to changes in interest rates than those of years past.

PIMCO has for several years now focused on the real interest rate – Fed Funds minus inflation – as the most legitimate indicator of neutrality.

Bill Gross, November 2005

The Fed has been on a mission for 15 months now to return money market interest rates to neutral and to impart a semblance of normality to the cost of borrowing.

Historically trading between 2% and 3%, which would imply a 4½ - 5½% range in nominal headline terms, we have suggested it will be different this time. Because the U.S. economy has evolved into a highly levered finance-based economy, it stands to our reason that this modern day version is more sensitive to changes in interest rates than those of years past. An

With January 2007 TIPS trading at a real yield of 1%, the implied level for real Fed Funds over the next 14 months hovers close to our previous forecast.

Economists/investment managers are also aware of the potency of a flattening yield curve shown in Chart 1. By the time 10-year and 2-year Treasuries reach parity, as is almost the case now, the economy is typically slowing and the Fed is at or near the end of its tightening cycle. Only Volcker with his need to strangle inflation out of the system persisted into negative yield curve territory for longer than a few months.

From Goldilocks to stagflation.

Real bond yields are extremely low already, suggesting that bond markets are already factoring in a significant slowdown in economic growth. However, bond markets are not yet priced for a significant pick-up in consumer price inflation.

Joachim Fels, Morgan Stanley, 14/9 2005

If investors in index-linked bond market were genuinely that fearful about the future, current equity prices would be hard to justify.

Once the higher possibility of extreme events is included in a valuation model that balances the returns that investors require against the risks they are prepared to accept, Mr Miles found the current yields on index linked government bonds of below 2 per cent extremely difficult to justify.

Chris Giles, Economics Editor, Financial Times, 12/9 2005

“There is a disconnect between values in the bond and equity markets,” Mr Miles said, the normal distribution was “spectacularly hopeless” at accounting for the leaps and troughs in economic activity of 21 countries over the past 170 years.

The research is based on recent advances in valuation techniques, discovered by Professor Robert Barro of Harvard University. These stress the importance of including the possibility of extreme events in any valuation model for bonds and equities.

Most extreme events are assumed to hit equities hard, but have little impact on safe government bonds. And history shows this is not just a theoretical nicety.

Wars, pandemics and revolutions have occurred much more often in the past than standard models, based on normal distributions or “bell curves”, suggest.

In America's deregulated financial market environment, liquidity-related impacts show up less in the various gauges of the money supply and credit flows and more in the form of movements in real interest rates.

With the Fed maintaining a long period of unusually accommodative policy financial assets have been supported by a steady stream of "carry trades."

Stephen Roach, 5/9 2005

"Livbolagen går mot ljusare tider"

Det finns dock ett hot kvar mot några av de ekonomiskt svaga bolagen.

Det är den låga räntan. Låg ränta kan tvinga fram ytterligare en sänkning av den så kallade högsta ränta, en ränta som används för att beräkna värdet på försäkringsbolagens åtaganden gentemot spararna.

DN 4/9 2005

En sänkning betyder, enkelt uttryckt, att bolagens eget kapital minskar i värde. För en del bolag innebär det sannolikt krav på kapitaltillskott från ägarna.

Den sista september sänks räntan från 3,5 procent till 3,25 procent. Det räknar Finansinspektionen med att alla bolag klarar. Men om ytterligare sänkningar tvingas fram, kan de sämst ställda bolagen få problem.

Bill Gross, July 2005:

Nouriel Roubini and David Backus Lectures in Macroeconomics

Chapter 5. Output and Real Interest Rates

If You search for real interest rates at Googles You find this page on their result page nr 2 (010914)

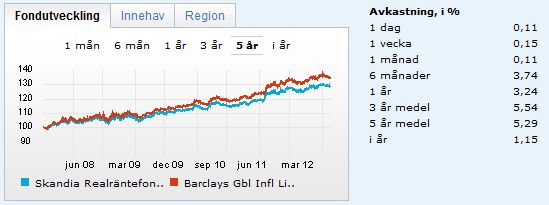

Efter tre år med kraftig värdeökning är den kortsiktiga risken i realräntefonder hög. Men på lång sikt är risken fortfarande minimal.

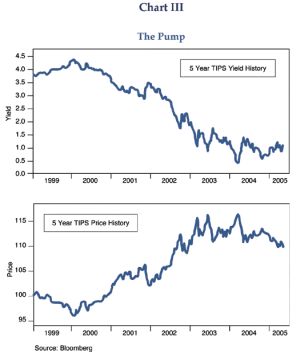

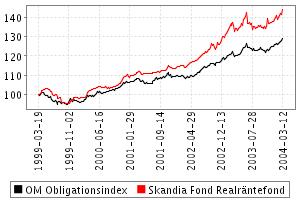

En av förra årets fondvinnare är Skandia Realräntefond, som steg 14,7 procent under 2002. Insättningarna har varit stora och intresset har gjort att även Robur, SEB och Öhman har startat egna realräntefonder det senaste halvåret.

Jonas Lindmark Morningstar 5/22/2003

Privata Affärer om Skandia Realräntefond

Skandia om Skandia Realräntefond

The increasing attention paid to growing U.S. current account deficits has bred nightmare scenarios of a sharp decline in the foreign-exchange value of the dollar and rising U.S. interest rates.

Financial markets, by contrast, appear more sanguine. Inflation-indexed bonds in the U.S. are yielding only about 1.5% in real terms, and the IMF's estimate of the long-term world real interest rate is about 2%.

Glenn Hubbard, dean of Columbia Business School, was chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush,

Wall Street Journal, 23/6 2005

Strange things are happening in the world economy: falling interest rates on long-term securities, declining spreads between returns on safe and riskier assets, large fiscal deficits and huge global current account “imbalances” should not, in normal circumstances, coincide. So what is going on?

The answer, in a nutshell, is a global excess of desired savings against the background of weak investment, low inflation and ever more integrated economies.

To understand the present we need to go back to the 1930s. The “paradox of thrift” was the most counterintuitive and, to the classically trained economist, morally, theoretically and practically objectionable idea in John Maynard Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, published in 1936, in response to the Great Depression.

Martin Wolf Financial Times June 13 2005

Häromveckan sålde en polare till mig en etta på 26

kvadratmeter på första våningen för 1,1 miljon

kronor.

Alla varningslampor blinkar rött. Och vi borde ha lärt oss vid det

här laget.

Vad sysslar vi med? Tror vi att det ska vara annorlunda

den här gången? Barnfamiljer som sitter och

tokbjuder över varandra och tjackar hus för 4,5 miljoner

kronor som betingade ett pris av 1,5 miljoner

för bara något år sedan.

Lena Sundström Metro 4/5 2005

Deflation is in the Cards. Yes Readers, that is correct.

The answer to the "Great Flation Question" is DEFLATION.

I am not going to wimp out and say "stagflation"

and rest assured it is not "inflation" which means that the "hyper-inflation" that many see coming is totally laughable.

Michael Shedlock 25/4 2005

Following the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement in 1971 with Nixon closing the "gold convertibility window" coupled with huge output expansion in Japan, Japanese currency reserves increased 260% between 1985 an 1988. Those dollars triggered a lending boom in Japan as well as incredible property bubbles and stock market bubbles. In 1989 the Nikkei index peaked above 38,000. Just as in the US in the late 1920's, earnings could not keep pace with market valuations and share prices started plunging. Japan repeatedly tried to stabilize the markets with injections of liquidity but Japanese property values plunged for 18 consecutive years and are still falling at the time of this writing.

The market does not know whether it should worry about growth or inflation, or possibly both: "stagflation".

The short answer is that growth has hit a soft patch, and inflationary pressures are increasing, but talk of stagflation is needlessly alarmist

Financial Times editorial 23/4 2005

What seems clear is that there are three main schools of thought

Philip Coggan FT 22/4 2005

The optimists believe the world has entered a new phase in which economies can grow rapidly without the inflationary pressures seen in the past.

In the late 1990s, they attributed this improvement to technological change; more recently, they have cited the influence of China and India, which are boosting global output while restraining labour costs.

The pessimists argue the boom is really down to the abundance of cheap credit.

Central banks reacted to the collapse of the dotcom bubble by slashing interest rates. This has kept consumption going by creating a bubble in housing but eventually, this excess credit will lead to disaster.

But here the pessimists are split. Some see the inevitable result as higher inflation; others as a deflationary bust.

One popular explanation for low bond yields is that Asian central banks are using their foreign exchange reserves to buy bonds as a means of preventing their currencies from rising against the dollar. They are uninterested in the price they pay; that is pushing yields down.

Richard Clarida in Wall Street Journal

Alan Greenspan stirred up the bond market by opining that the then-low level of bond yields -- in tandem with strong growth, $50 oil

and a succession of Fed rate hikes since June -- represented a "conundrum."

From the TIPS market, we learn that the expected real return over the next 10 years on a riskless investment in government bonds is 1.81%.

11/4 2005

From January 1980 to January 2005, M3 US grew 420%.

Dow Jones Industrial Average returned 1,098%

Jim Jubak CNBC 1/4 2005

From January 1980 to January 2005, M1, the Federal Reserve's most conservative measure of the money supply in the United States, grew by 252%. M3, a measure that captures some of the money created by Wall Street's institutions, grew 420%.

At the same time as the money supply was growing, the cost of tapping into that river of cash was falling: The Fed funds rate, the cost for a bank to borrow overnight from the Federal Reserve, fell from 13.8% in January 1980 to 1% in January 2004.

No wonder that with money so easy to borrow (thanks to that jump in supply) and so cheap (thanks to low interest rates) that the price of assets such as stocks and bonds that you could buy with borrowed money soared.

From January 1980 to January 2005, the Dow Jones Industrial Average returned 1,098% and the Nasdaq Composite Index returned 1,175%.

Doom on Wall Street (chart Dow 1972-1997) Note 1974-1975

”Den enda period sedan 1700 då vår uppskattade realränta varit så här låg var åren under och närmast efter andra världskriget

Den genomsnittliga realräntan har varit 3 procent under tre århundraden.

Gunnar Örn, DI 30/3 2005

Morgan Stanley konstaterar att priserna stigit med genomsnitt 1,6 procent per år sedan år 1700. Samtidigt har den genomsnittliga, nominella räntan varit 4,6 procent.

Den genomsnittliga realräntan har alltså varit 3 procent under tre århundraden.

I dag är realräntorna betydligt lägre. En hel procentenhet under det långsiktiga genomsnittet.

Morgan Stanley har utvecklat en egen modell för hur hög realräntan borde vara i dagens läge. Svaret är åtminstone 1 procentenhet högre.

”Den enda period sedan 1700 då vår uppskattade realränta varit så här låg var åren under och närmast efter andra världskriget”, heter det i analysen.

In an environment in which profits, business success, and jobs themselves have been driven in substantial part by a 20-year trend of lower interest rates, an observer must make the unmistakable conclusion that we have come to the end of the road.

Age does have some benefits if only in knowing what not to do if given a second chance.

PIMCO Founder and CIO Bill Gross addressed the graduating MBA class at Duke University's Fuqua School of Business on May 8, 2004.

A Guide to Global Inflation-Linked Bonds

a burgeoning global market that has more than tripled in size over the last six years, growing from $145 billion in 1997 to $551 billion at the end of 2003.

PIMCO January 2005

In 1981, the modern inflation-linked bond market began when the United Kingdom leveraged the strategy with a ?1 billion sale. Shortly thereafter, the trend caught on and Sweden, Canada and Australia also issued inflation-linked bonds. In 1997, the U.S. entered the market with its first auction of Treasury Inflation Indexed Securities, often referred to as "TIPS."

The 10-year Treasury note yield jumped over 4.6%.

Between the Fed's announcement and the close, The Dow Jones industrials fell more than 138 points.

CNBC 22/3 2005

Financial markets were shaken by the inflation concern, despite a substantial drop in crude oil prices. Interest rates jumped, and stocks threw away a pre-announcement rally.

The Dow Jones industrials fell nearly 95 points on the day. Between the Fed's announcement and the close, the blue-chip average fell more than 138 points.

Essentially what we are saying is that all global asset prices markets will remain severely distorted as long as the main suppliers of excess savings to the world economy - the Japanese private investors - continue to live in a zero-rate environment.

If the Japanese economy regains momentum and the Nikkei manages to break through the 12,000 level. The bear market in global bonds would then resume in a big way.

Anatole Kaletsky at Investorsinsight 22/3 2005

As Keynes said, the market can remain irrational much longer than the rational investor can remain solvent.

Our first conclusion, therefore, is that the crash in bond markets which we expected to see on the basis of the past two economic cycles - 1994 and 1983/4 - will be slower and less disruptive than we thought. From a long-term perspective, however, a slow rise in bond yields is probably more ominous than a sharp bounce. Technically, bond yields are creating a huge multi-year base. In terms of economic fundamentals, the bond market's refusal to push long-term interest rates higher will offset the restrictive effects of monetary tightening. As a result, long-term inflationary pressures will intensify, fiscal disciplines on governments will be loosened and all asset prices will be pumped up.

Secondly, the present asset inflation - and rolling financial bubbles - will last for a surprisingly long time. If we are right about the dominant role of Japanese private savers among the zombie bond investors, then global liquidity and asset prices will depend less on US monetary policy or the strength of the dollar, than the level of interest rates in Japan. Given the likelihood that Japanese short rates will remain at or near zero for the next two years - and probably until the end of the decade (see Anatole's Notes from his Japan Trip) - this means US and euro rates long rates will remain "unnaturally" low for a very long time, regardless of what the Fed may do (or say). If this turns out to be true, then the implications for global economic conditions and for equity, property and other asset prices, should be extremely bullish.

If Japanese investors rediscovered their domestic equity market, they might stop their zombie bond-buying and conditions in the world financial markets would be transformed.

US, Germany, France and UK face junk debt status

Rapidly rising pension and healthcare spending

Financial Times 21/3 2005

Rapidly rising pension and healthcare spending will reduce the debt status of the world's richest industrialised countries to junk within 30 years unless their governments move quickly to balance budgets and reduce outgoings, a report published on Monday warns.

Standard & Poor's, the credit ratings agency, says if fiscal trends prevail, the cost of ageing populations will fuel downgrades of France, the US, Germany and the UK from investment grade to speculative, or junk, category France by the early 2020s, the US and Germany before 2030 and the UK before 2035.

56 private economists surveyed by the Wall Street Journal Online this month see another force at work:

expectations for low inflation.

Alan Greenspan called it a "conundrum": Long-term interest rates have remained low despite the Federal Reserve's campaign to raise rates on the short end.

Wall Street Journal 10/3 2005

The Mystery of Low Interest Rates

U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan recently called the declines a "conundrum."

By ROBERT J. SAMUELSON The Washington Post March 7, 2005

Theories abound to explain the mystery. Here are three, courtesy of economist David Wyss of Standard & Poor's.

There are also gloomier theories.

Economist John Makin of the American Enterprise Institute says that low long-term rates signal fears of a weakening economy. A weaker economy would presumably mean less inflation and credit demand -- both justifying lower long-term rates.

Among worriers, the fear is that cheap credit has created a housing "bubble." In the year ending in September, average U.S. home prices rose 13%, reports one survey. In Nevada they rose 36%, in California, 27% and in Florida, 20%. Higher housing prices have supported consumer spending -- people borrowed against home values -- and free-spending Americans have bolstered the U.S. and global economies. If the cycle reversed, the consequences might be grim. Falling home prices. Sickly consumption. Global slump.

My view is that low interest rates are mainly a good sign. They reflect not only low inflation in the U.S. but growing confidence that it will stay low. We may be reverting to the 1950s, when this was the norm. In 1959 the rate on the 10-year Treasury bond averaged 4.33%.

This is a reassuring notion; it could also be wrong.

Over the past couple of weeks, investors have been falling over themselves to snap up new offerings, whether they be long dated or short term, high yield or sovereign.

Beneficiaries of this feeding frenzy have included the French government, which became the first from the Group of Seven leading industrialised countries to issue a 50-year bond.

In what must count as a triumph of hope over experience for anyone with the slightest recollection of how inflation can suddenly take hold, it was priced to yield just 4.21 per cent a year.

Financial Times editorial 5/3 2005

In the US, Centex, a US housebuilder, sold $1bn of asset-backed paper and was rewarded with best ever prices. The tranche maturing after one year yielded a record low of seven basis points, or seven-hundredths of 1 per cent, over the one-month London Interbank Offered Rate (Libor).

The yield spread, or premium over government bonds, of emerging market debt has shrunk dramatically. That of many corporate bonds has fallen to levels last seen in 1998, just before the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management, a hedge fund, plunged the world into a big financial crisis.

It is difficult to explain the falling yields, which have brought real yields after adjustment for inflation to unusually low levels, by developments in the global economy. Despite high and recently rising oil prices, world economic activity is expanding at a reasonable pace.

It is little wonder that Alan Greenspan, Fed chairman, spoke last month of a bond market "conundrum". One could go further and argue that bond markets are falling prey to irrational exuberance similar to that seen in equity markets before the dotcom bust.

If so, one unpalatable conclusion is that we are living through a bond market bubble.

In today's market, the watchwords must be Caveat Investor.

The idea that central banks should track asset prices is hardly new.

In 1911 Irving Fisher, an American economist, argued in a book, “The Purchasing Power of Money”, that policymakers should stabilise a broad price index which included shares, bonds and property as well as goods and services.

The Economist 24/2 2005

Det finns bara en stensäker placering: att köpa statens realränteobligationer.

Spararen kompenseras helt för inflationen och är garanterad en fast real ränta under spartiden.

I dagsläget får den som köper en 5-årig obligation 1,34 procent per år och 1,51 procent om pengarna binds i åtta år.

SvD 22/2 2005

Realränteobligationer har aldrig blivit någon succé bland hushållen. I fjol minskade rent av försäljningen, visar årsredovisningen från Riksgäldskontoret.

Hur hög är då denna neutrala "lagomränta" som Fed siktar på?

Där är osäkerheten desto större. Buden varierar från 3,0 till 5,0 procent. Och det är ett avsevärt spann.

- Vi vet i dagsläget inte var den aktuella räntan ligger, förklarade Fedchefen Alan Greenspan nyligen. Banken får pröva sig fram.

Lars-Georg Bergkvist SvD Näringsliv 27/2 2005