Finance Crisis

Home - Index - News - Kronkursförsvaet 1992 - EMU - Economics - Cataclysm - Finanskrisen - Houseprices

Leverage and Deleveraging

Debt cannot rise faster than GDP forever, but it may do so for quite a while.

Kenneth Rogoff Project Syndicate 4 March 2019

Global outstanding debt in the form of corporate bonds issued by non-financial companies has hit record levels,

reaching almost USD 13 trillion at the end of 2018.

This is double the amount outstanding in real terms before the 2008 financial crisis, according to a new OECD paper.

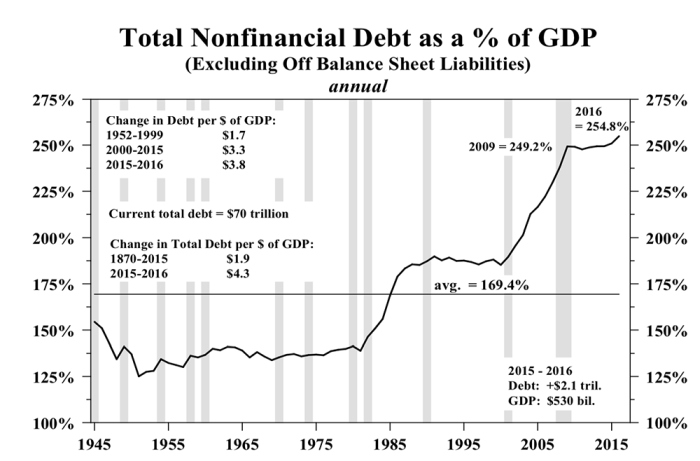

OECD 25/02/2019The fundamental question is why economic growth has become so debt dependent

Adair Turner 9/11 2018

zombie companies

I talked about our growing debt problem and how it could trigger a crisis.

Excessive leverage may light the fuse, but the real problems are deeper.

John Mauldin 2 November 2018

Michael Milken pioneered the junk bond (politely “high yield”) market

Ultimately, businesses expand and hire when they think consumers are ready to buy their products.

US government deficit will be (drumroll, please) approximately $1.4 trillion per year for the next five years, which will mean $29 trillion total debt by 2024.

And that’s without a recession. Throw in a recession, and we’ll get to $30 trillion long before then.

Next Bubble U.S. Government Bonds

Bank lending in 2018 looks a lot like bank lending pre-2008.

Worse, macroeconomic policies, designed as a methadone fix to see a debt-addicted world though the post-crisis years,

have actually led to increased leverage outside the banking sector

FT 9 October 2018

There was no deleveraging at all

---just more of the same;

and that the debt-based financial fragility that caused the system to literally meltdown in the fall of 2008

has merely metastized from $52 trillion to nearly $69 trillion.

David Stockman's Contra Corner 17 July 2018

World debt ratios have spiralled to record levels during the era of super-easy money and

markets are showing tell-tale signs of late-cycle excess,

leaving the international financial system acutely vulnerable to a jump in borrowing costs.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Telegraph 24 June 2018

Any reversal in our fortunes could be “quick and sharp”, says the Bank for International Settlements, the venerable global watchdog based in Switzerland and the scourge of dissolute practice.

The Global Debtberg — $ 238 Trillion And Counting

David Stockman's Contra Corner

I think the mother of all Minsky moments is building.

It will not be an instant sandpile collapse, but instead take years because we have $500 trillion of debt to work through.

We cannot accurately predict when the avalanche will happen.

John Mauldin 1 September 2018

The entire world went into debt for the equivalent of tropical vacations and, having now enjoyed them, realizes it must pay the bill. The resources to do so do not yet exist.

So, in the time-honored tradition of lenders everywhere, we extend and pretend.

But with our ability to pretend almost gone, we’re heading to the Great Reset.

John Mauldin 8 June 2018

I’ve been analogizing our fate to a train wreck you know is coming but are powerless to stop. You look away because watching the disaster hurts, but it happens anyway.

That’s where we are, like it or not.

The only sustainable debt burden is one that can be managed even during cyclical downturns

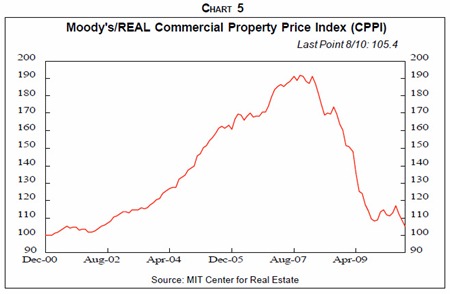

Regulatory authorities should take particular care to prevent real-estate bubbles

Michael Heise Project Syndicate 15 May 2018

Despite years of deleveraging after the 2008 global financial crisis, debt remains very high – and yet we have now returned to an expansionary credit cycle. According to the Bank for International Settlements, total non-financial private and public debt amounts to almost 245% of global GDP, having risen from 210% before the financial crisis

Regulatory authorities should take particular care to prevent real-estate bubbles, because real estate constitutes a huge share of overall wealth and a key source of collateral in finance.

Today’s febrile political environment certainly will not simplify matters. But the consequences of shying away from such choices could be devastating.

Michael Heise is Chief Economist of Allianz SE and the author of Emerging From the Euro Debt Crisis: Making the Single Currency Work.

Canada’s housing market flirts with disaster

FT The Big Read, 8 February 2018

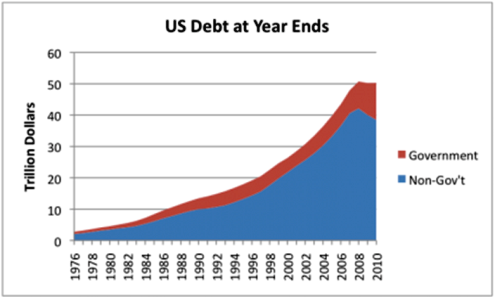

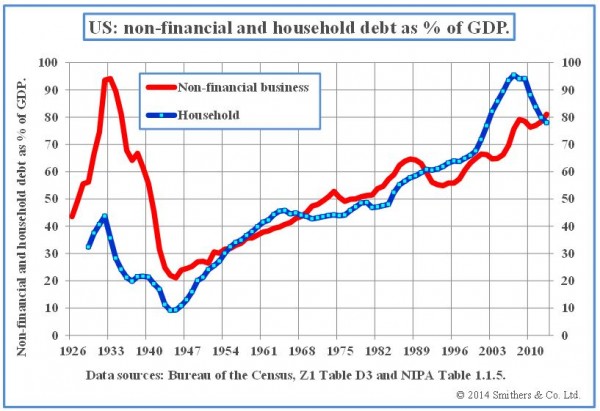

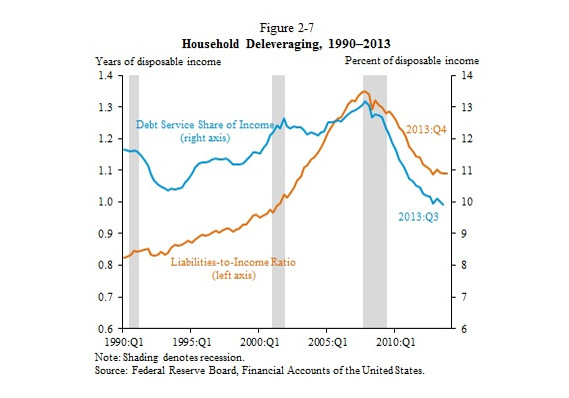

During the first 20-years of the Greenspan-incepted era of Bubble Finance, household leverage ratios exploded.

Whereas wage and salary incomes rose by $4.2 trillion or 2.9X, household liabilities soared by nearly $12 trillion or 5.2X.

David Stockman 5 February 2018

Over the two decades, therefore, household leverage ratios (liabilities to earned income) nearly doubled from 124% to 224%.

It’s not just China.

Global debt rose to a record $233 trillion in the third quarter of 2017,

more than $16 trillion higher from the end of 2016, according to the Institute of International Finance.

Bloomberg 22 January 2018

Fed was focused on unemployment and inflation during the 1990s and early 2000s,

they failed to do anything about the massive buildup of debt. This laid the groundwork for the financial crisis.

John Mauldin Lacy Hunt January 2018

Household debt in the US surpassed its pre-crisis peak in the first quarter

Consumer debt balances totalled $12.73tn at the end of the first quarter, exceeding the 2008 peak of $12.68tn.

FT 17 May 2017

Svenskarnas bostadslån fortsätter att öka och var i slutet av november månad

2 882 miljarder kronor.

Louise Andrén Meiton, SvD 28 december 2016

Just over $6.6tn

Global debt sales reached a record in 2016

led by companies gorging on cheap borrowing costs

breaking the previous annual record set in 2006

FT 27 December 2016

Corporate bond sales climbed 8 per cent year on year to $3.6tn,

led by blockbuster $10bn-plus deals to finance large mergers and acquisitions.

The real, less respectable reason why companies engage in buybacks,

namely to boost earnings per share by shrinking the equity.

Plender

The vast size of China’s debt mountain — which stands at over 250 per cent of gross domestic product,

up from 125 per cent in 2008 — means that even minor increases in short-term interest rates

may squeeze corporate activity and precipitate defaults

FT 8 December 2016

Alex Wolf, emerging markets economist at Standard Life Investments, argues that default risks are rising

because more and more corporations are relying on the short-term money market to raise the finance they need to repay existing debts.

Owners of entry-level homes, those in the $150,000 to $300,000 range —

have more debt and less equity now than they did in 2005, at the height of mortgage mania.

MarketWatch 17 October 2016

The primary purpose of doing QE is — or should be — to expand purchasing power

John Greenwood, FT 30 May 2016

The Chinese Communist Party is now officially worried about mounting debt.

“A tree cannot grow up to the sky—high leverage will definitely lead to high risks,”

said a front-page commentary in the People’s Daily on May 9.

Bloomberg 13 May 2016

Den höga privata skuldsättningen kombinerat med högt värderade och stigande fastighetspriser

och en av världens största banksektorer gör att en framtida kris riskerar bli än värre än krisen under 1990-talet.

Fredrik N.G. Andersson, Andreas Bergh och Anders Olshov, 28 april 2016

What ever happened to deleveraging?

McKinsey notes that gross debt has increased about $60 trillion – or 75% of global GDP – since 2008.

Michael Spence, Project Syndicate 27 April 2016

In the years since the 2008 global financial crisis, austerity and balance-sheet repair have been the watchwords of the global economy. And yet today, more than ever, debt is fueling concern about growth prospects worldwide.

A global economy that is levering up, while unable to generate enough aggregate demand to achieve potential growth, is on a risky path.

Michael Spence, a Nobel laureate in economics, is Professor of Economics at NYU’s Stern School of Business,

Distinguished Visiting Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University,

Academic Board Chairman of the Asia Global Institute in Hong Kong, and Chair of the World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on New Growth Models.

He was the chairman of the independent Commission on Growth and Development, an international body that from 2006-2010 analyzed opportunities for global economic growth, and is the

author of The Next Convergence – The Future of Economic Growth in a Multispeed World.

The FOMC dares not tighten despite core inflation reaching 2.3pc

because it is so worried about financial markets.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard 17 MARCH 2016

Here Comes The Red Swan And Other Reasons To Be Very Afraid

China is a monumental doomsday machine that bears no more resemblance

to anything that could be called stable, sustainable capitalism

than did Lenin’s New Economic Policy of the early 1920s.

David Stockman 25 February 2016

The $29 Trillion Corporate Debt Hangover That Could Spark a Recession

The seven-year-old global growth model based on cheap credit from central banks is running out of steam

Bloomberg 28 January 2016

Much of the cheap credit accumulated by companies was spent on a $3.8 trillion M&A binge, and to fund share buybacks and dividend payments. While that tends to push up share prices in the short term,

bond investors would rather see that money spent on strengthening the business in the long term.

Stephen King: Why monetary stimulus has not done its job

via Rolf Englund blog 2016-01-23

China in the Debt-Deflation Trap

In 1933, Irving Fisher was the first to identify the dangers of over-indebtedness and deflation

Andrew Sheng and Xiao Geng

Project Syndicate 24 September 2015

In 1933, Irving Fisher was the first to identify the dangers of over-indebtedness and deflation, demonstrating their contribution to the Great Depression in the United States.

Forty years later, Charles Kindleberger applied the theory in a global context, emphasizing the problems that arise in a world lacking coordinated and consistent monetary, fiscal, and regulatory policies, as well as an international lender of last resort.

In 2011, Richard Koo used Japan’s experience to highlight the risks of a prolonged balance-sheet recession, when over-stretched debtors deleverage in order to rebuild their balance sheets.

To prevent asset bubbles from collapsing and buy time for more sustainable policy fixes, advanced-country central banks implemented massive monetary easing and cut interest rates to zero.

Unfortunately, policymakers in most countries wasted the time they were given; moreover, so-called quantitative easing had far-reaching spillover effects.

The reason why central banks have increasingly embraced unconventional monetary policies is that the post-2008 recovery has been extremely anemic.

Such policies have been needed to counter the deflationary pressures caused by the need for painful deleveraging in the wake of large buildups of public and private debt.

Simply put, we live in a world in which there is too much supply and too little demand.

The result is persistent disinflationary, if not deflationary, pressure, despite aggressive monetary easing.

Nouirel Roubini, MarketWatch Feb 2, 2015

Richard Koo’s ‘The Escape from Balance Sheet Recession and the QE Trap’ should be read

Review by Martin Wolf, FT January 4, 2015

The Escape from Balance Sheet Recession develops this argument, laid out in The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics (2011),

Richard Koo is chief economist of the Nomura Research Institute

Balance sheet recession is a development of the concept of “debt deflation”, advanced by American economist Irving Fisher during the Great Depression. Fisher noticed that, if the price level falls, the real value of debt will rise. If many people are highly indebted, the economy then risks falling into a vicious downward spiral.

The Escape from Balance Sheet Recession and the QE Trap

The macroeconomics of deleveraging or what Richard Koo of Nomura Research calls “balance sheet recessions”

The essential idea is that since income has to equal expenditure for the economy, as a whole,

(which is the same things as saying that saving equals investment)

so the sums of the difference between income and expenditures of each of the sectors of the economy must also be zero.

These differences can also be described as “financial balances”.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 19 July 2012

Geneva Report warns record debt and slow growth point to crisis

Predicts interest rates across the world will have to stay low for a “very, very long” time

to enable households, companies and governments to service their debts and avoid another crash.

By Chris Giles, FT Economics Editor September 28, 2014

Balance sheet recession

Giving the banks more money for lending is surely not the answer to a demand problem

Call them stability bonds instead of euro bonds, if that makes the idea more palatable in Berlin.

Wolfgang Munchau, FT June 29, 2014

A combination of sharp falls in asset prices and debt levels has caused financial crises.

This was the case in the US in 1929, in Japan in 1990 and worldwide in 2008.

Andrew Smithers, ft.com blogs, 11 March 2014

Nice chart

Among the major disappointments of the weak recovery we have seen in major economies over the past three years has been the failure of debt levels to fall back significantly since 2008.

Hello! I’m Andrew Smithers; I studied economics at Cambridge and used to run the fund management business at S G Warburg which became Mercury Asset Management and is now BlackRock.

The White House’s economics team, like many economic forecasters, expects the economy to improve. Here’s why.

MarketWatch 10 March 2014

As the chart shows, households have made progress paying off debt. Household debt has dropped from 1.4 times annual disposable income, in the good old days of the fourth quarter of 2007, to 1.1 times in the fourth quarter of 2013.

Debt service also has dropped, from 13% of disposable income in the fourth quarter of 2007 to 10% in the third quarter of 2013.

Deleveraging

Both households and financial institutions have reduced their leverage,

but they still have a long way to go to reach their previous trend relationship to GDP.

A. Gary Shilling, Bloomberg, 5 March 2014

The U.S. and other economies continue to deleverage in the aftermath of the global recession that capped 25 years of debt accumulation, especially by households and the financial sector.

The ratios of debt to gross domestic product in these two areas leaped three- and fourfold from the early 1980s to the onset of the 2007-2009 global crisis.

Both households and financial institutions have reduced their leverage since then, but they still have a long way to go to reach their previous trend relationship to GDP.

I am a strong believer in reversion to long-established trends.

We face about four more years of deleveraging, bringing the total span to about 10 years - the normal duration of this process after major financial bubbles.

(This is the first in a four-part series.)

The EU wants money-market funds to hold more reserves.

Furthermore, EU finance ministers are drafting rules for winding down troubled banks that would force stock- and bondholders to take a hit before any taxpayer bailouts are approved.

The EU plan also would require banks to contribute to a 55 billion-euro ($75.5 billion) bailout fund.

A. Gary Shilling, 6 March 2014

Put Your Portfolio on the Defensive

A. Gary Shilling, 7 March 2014

Other warning signs include the high level of stock-market capitalization in relation to gross domestic product. At 141 percent, it’s almost back to the mid-2000s housing-bubble peak of 144 percent, which was only surpassed at the end of the dot-com bubble in early 2000, when it reached 174 percent.

There are considerable questions about stock performance this year, even in the absence of a shock.

Will price-earnings ratios, which accounted for two-thirds of the 30 percent increase in the S&P Index last year, continue to rise?

Peaks often are reached when everyone has been sucked in.

Then, a major shock could force investors to focus on the slow global economy

A. Gary Shilling, 10 March 2014

A cautionary tale emerges from the recently released transcripts of Federal Reserve policy meetings at the height of the 2008 financial crisis.

They show that, like China today, the Fed had all the money it needed to bail out any financial institution,

yet central bankers admitted they were “behind the curve” and failed to move swiftly before runs on banks, notably Bear Stearns Cos. LLC and Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.

(This is the last in a four-part series.)

Who’s right: Yale’s Stephen Roach or Harvard’s Martin Feldstein

To Roach, 68, Americans are still working to rebuild savings and will be slow to increase spending

Feldstein, 74, predicts “we finally are going to see a good year in 2014,”

thanks to stock-market and home-price gains that have boosted household wealth and given consumers the confidence to spend.

Bloomberg, 24 January 2014

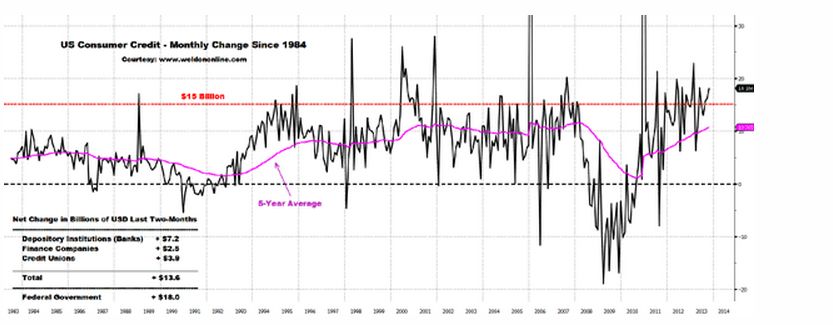

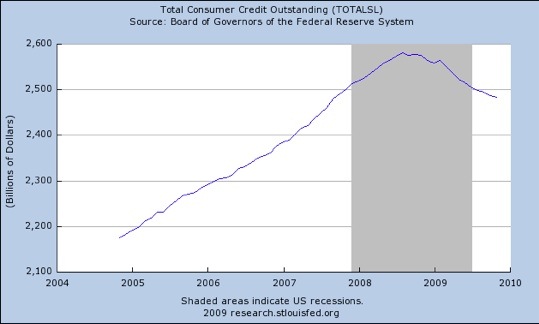

More months of double-digit growth of Consumer Credit over the last three-years,

than during ANY other period in the post-WWII

The stock market has replaced the housing market as that collateral base against which the US consumer is now borrowing

Greg Weldon, via John Mauldin, 22 January 2014

As seen in the chart below, we can identify more months of double-digit (as in more than $10 billion) growth

in the Fed's own measure of Consumer Credit over the last three-years,

than during ANY other period in the post-WWII timeline.

Note further, that the 5-Year Average of monthly borrowing has almost returned to the pre-2007 crisis highs.

In essence, we can very comfortably argue that the Fed has facilitated another credit-fueled recovery, wherein the US consumer is, again, borrowing aggressively against a collateral base that is 'defined' by paper wealth, rather than 'real' income growth.

The stock market has replaced the housing market as that collateral base against which the US consumer is now borrowing hand-over-fist.

March 24, 2013 1:55 am by Gavyn Davies

"promising to pay nothing forever"

Balance sheet obstacles to sustained demand growth mean the EU faces two or three more years of recession.

The balance sheet recession is caused by excessive leverage:

zombie banks throughout the EU, excessive sovereign debt and deficits in the periphery,

and excessive household indebtedness in many countries.

Willem Buiter, Finanacial Times 8 May 2013

Consumer debt rose in the final months of 2012 for the first time in four years,

Total consumer debt rose 0.3 percent to $11.34 trillion

Consumer debt peaked in the third quarter of 2008 as the global financial crisis was taking hold.

Since then, debt has fallen by about by 10 percent, or $1.3 trillion,

in large part due to a drop in outstanding mortgages as Americans modified or defaulted on their loans.

CNBC Reuters, 28 February 2013

Kommentar av Rolf Englund:

Dagens etablerade sanning:

Högre statsskuld, Bad News. Högre privata skulder: Good News

En snabb minskning av hushållens skulder skulle slå hårt mot konsumtionen och är inte önskvärd.

Det säger finansminister Anders Borg och spår att bostadsmarknaden kommer att befinna sig i stagnation de kommande 10-20 åren.

Dagens Industri 26 februari 2013

Why won’t those wretched banks lend money?

Deleveraging, Basel Capital rules, Liquidity coverage ratios

Gillian Tett, Financial Times, October 11, 2012

När staten och den privata sektorn samtidigt kapar sina skuldberg är det svårt att få schvung på ekonomin

Dagens Nyheter, huvudledare, 15 juli 2012

Kommentar av Rolf Englund

Det är inte svårt. Det är omöjligt. Om man inte kan öka exporten och minska importen

Det gör man genom att växelkursen sjunker, eller, om man har euron, genomför en intern devalvering

Why Deleveraging Still Rules Markets in 2013

I foresee about five more years of deleveraging

A. Gary Shilling, Bloomberg 28 January 2013

The Siren Song of 'Beautiful Deleveraging'

Charles Hugh Smith, via Peak Prosperity, September 2012

In a world of rising sovereign debts and an overleveraged, over-indebted private sector, history suggests there are only three possible ways out: gradual deleveraging, defaulting on the debt, or printing enough money to inflate away the debt.

The Status Quo in Japan has pursued this strategy for 20 years, and the Status Quo in Europe and the U.S. have pursued it for the past four years, ever since the global financial system imploded in 2008.

Unsurprisingly, the conventional view is that it’s working "beautifully". Housing has bottomed, stocks have doubled since their March 2009 lows, households are slowly deleveraging, inflation is modest, and growth is sluggish but steady.

All we need to do, we’re told, is stay the course for a few more years, and the stage will be set for a return to the rapid growth of the bubble years.

After almost four years of $1tn-plus fiscal deficits, near-zero policy rates, and a Fed balance sheet that is pregnant with triplets, how can we not have some growth, any growth?

The government spigots have been turned on to such an extent that if this were a normal plain-vanilla cycle, the economy would have ballooned at an 8 per cent average annual rate since the “great recession” ended three years ago.

The fact that it has expanded at barely more than a 2 per cent pace – the weakest recovery ever – speaks to the secular headwinds from debt-burdened households, structural unemployment and retrenchment at state and local government level.

David Rosenberg, Financial Times, 1 August 2012

Let us look at alternative ways of accelerating deleveraging.

Broadly there are two: capital transactions and default.

The latter, in turn, comes in two varieties: plain vanilla default and inflationary default.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times 30 July 2012

A wave of bankruptcies is likely to trigger a further massive reduction in the actual and perceived net worth of financial institutions. That must, in turn, mean either bail-outs or losses for the creditors of these institutions, potentially triggering yet another financial panic. For this reason, the urge to trade their way out of the losses, instead, is understandably very strong. This is one reason why the aftermath of crises tends to be so long, drawn out and painful.

Nevertheless, regulators can insist that asset prices be marked down swiftly and loans restructured. If that threatens the insolvency of intermediaries, they will need to ensure that institutions are swiftly recapitalised, either by converting debt into equity or by providing outside capital.

The macroeconomics of deleveraging or what Richard Koo of Nomura Research calls “balance sheet recessions”

The essential idea is that since income has to equal expenditure for the economy, as a whole,

(which is the same things as saying that saving equals investment)

so the sums of the difference between income and expenditures of each of the sectors of the economy must also be zero.

These differences can also be described as “financial balances”.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 19 July 2012

Vi lever med våra etablerade sanningar

Det är antaganden som sällan eller aldrig ifrågasätts, därför att vi intalar oss att de måste vara korrekta

En sådan så kallad sanning är att Japan fullständigt misslyckats med hanteringen av sin finanskris som bröt ut kring 1990

Peter Wolodarski Signerat DN 13 januari 2013

Today, the US private sector is saving a staggering 8 per cent of gross domestic product – at zero interest rates, when households and businesses would ordinarily be borrowing and spending money.

But the US is not alone: in Ireland and Japan, the private sector is saving 9 per cent of GDP; in Spain it is saving 7 per cent of GDP; and in the UK, 5 per cent.

Interest rates are at record lows in all these countries.

Richard Koo, Financial Times, November 4, 2012

This is the result of the bursting of debt-financed housing bubbles, which left the private sector with huge debt overhangs – notably the underwater mortgages – giving it no choice but to pay down debt or increase savings, even at zero interest rates.

The big story continues to be one of private sector de-leveraging

David Levy, of the Jerome Levy Forecasting Center, labels sluggish economies with huge policy stimuli a “contained depression”.

In the US total private sector debt rose from 112 per cent of GDP in 1976 to a peak of 296 per cent in 2008

In 2007, US gross private borrowing was 29 per cent of GDP. In 2009, 2010 and 2011, however, it was negative.

Martin Wolf, Financial Times 10 July 2012

A must read

Five years after the financial crisis hit the US and forced lenders there to shrink, Europe, too, is learning the meaning of “deleveraging”.

This is the process, in financial jargon, of unwinding excessive “leverage” – essentially the ratio of a bank’s assets, or loans, to its equity capital.

Patrick Jenkins and Brooke Masters, Financial Times, May 3, 2012

The International Monetary Fund last month brought the message home to anyone who still believed the European economy – built on a glut of credit-funded borrowing and consumption for a decade and more running up to the crisis – could avoid a sharp correction.

It warned that unless policy makers took preventive action, Europe’s banks would shrink their assets by €2tn in the next 18 months.

“Synchronised and large-scale deleveraging” would, it said, be more severe than previously anticipated, posing a serious risk to economic growth.

The broader challenge in the next couple of years will be for banks and policy makers to strike a balance between undertaking necessary deleveraging and starving Europe – particularly its small-business backbone – of funding.

As Ben Bernanke, chairman of the Federal Reserve, explained in an important speech on April 13,

central banks have expanded their balance sheets because those of the private financial sector collapsed.

That is what a lender of last resort is supposed to do during a severe panic. We have known this since the 19th century

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, 1 May 2012

Then, as and when private lending recovers, the central banks will reverse course, selling assets into the market and reducing their credit to banks.

But this will be a lengthy and fragile recovery.

Central banks are not playing for small stakes.

Chairman Ben S. Bernanke

Some Reflections on the Crisis and the Policy Response

April 13, 2012

The high cost of disorderly deleveraging

In the last quarter of 2011 alone, the 58 banks in the IMF’s sample reduced assets by almost 580 bn dollar.

John Plender, Financial Times April 24, 2012

IMF’s Global Financial Stability Report

World Economic Outlook

“it is ... critical to break the adverse feedback loops between subpar growth,

deteriorating fiscal positions, increasing recapitalisation needs, and deleveraging ..

Martin Wolf, Financial Times, April 24, 2012

Why Deleveraging Still Rules Markets in 2013

I foresee about five more years of deleveraging

A. Gary Shilling, Bloomberg 28 January 2013

The investment scene in the U.S. and elsewhere is dominated by a number of forces:

the deleveraging of private economic sectors and financial institutions;

the monetary and fiscal responses to the resulting slow growth and financial risks;

competitive devaluations;

the fixation of investors on monetary ease that obscures weak real economic activity;

and central bank-engineered low interest rates that have spawned more distortions and investor zeal for yield, regardless of risk.

The financial sector began its huge leveraging in the 1970s,

as the debt-to-equity ratios of some financial institutions leaped.

The household sector followed in the early 1980s.

That’s when credit-card debt ballooned and mortgage down payments dropped from 20 percent, to 10 percent, to 0 percent.

We even reached negative numbers at the height of the housing boom as home-improvement loans added to conventional mortgages pushed debt-to-equity ratios above 100 percent.

The deleveraging process for both of these sectors has begun, though it has a long way to go to return to the long-run flat trends.

I foresee about five more years of deleveraging, bringing the total span to about 10 years,

which is about the normal duration of this process after major financial bubbles.

A. Gary Shilling:

Will U.S. Avoid a Recession in 2012?

April 2012

Gary Shilling is looking for a brand new cyclical recession beginning in 2012

The economy, he says, is like a four-cylinder engine, and a recovery usually requires all four to be firing.

They are consumer spending, employment, housing and the reversal of the inventory cycle.

Howard Gold, MarketWatch 24 June 2011

The Coming Collapse in Housing

By Gary Shilling at John Mauldin 17/11 2006

Bankernas stora problem: Ytan = Basen x Höjden

Rolf Englund blog, 16 Februari 2012

“Deleveraging” is an ugly word for a nasty journey towards lowering excessive debt after a credit bubble

What makes the effort particularly difficult now is that it affects the US and other large economies.

This is a global, not just a local, event

Martin Wolf, March 13, 2012

In January, the McKinsey Global Institute published an updated version of its invaluable research on deleveraging.* It is a sobering document: it shows that deleveraging has a long way to go; happily, it also shows that the US economy is the most advanced in deleveraging.

As the McKinsey Global Institute study points out, it is also false. Sweden and Finland, both hit by big crises in the early 1990s, are good examples of why this is so.

Total debt-to-GDP levels in the 18 core countries of the OECD rose from 160 percent in 1980 to 321 percent in 2010.

Disaggregated and adjusted for inflation, these numbers mean that the debt of nonfinancial corporations increased by 300 percent,

the debt of governments increased by 425 percent, and the debt of private households increased by 600 percent.

David Rhodes and Daniel Stelter, via John Mauldin, January 2012

But the costs of the West's aging populations are hidden in the official reporting.

If we included the mounting costs of providing for the elderly, the debt level of most governments would be significantly higher. (See Exhibit 1.)

It's the classic pyramid, or snowball scheme, practiced by thousands of con artists after Ponzi. The most spectacular case was that of New York financier Bernard Madoff, who was responsible for losses of about $20 billion by 2008. Snowballs are set into motion, becoming bigger and bigger as they roll along. In the worst case, they end in an avalanche that takes everything else with it.

Ponzi

Western economies have not acted much differently than the fraudster Madoff.

Almost everyone - in Europe and in the United States - has been living beyond their means, from consumers to politicians to entire countries

Alexander Jung, Der Spiegel, 5 January 2012

Some aspects of the economic system in the industrialized countries resemble a gigantic Ponzi scheme. The difference is that this version is completely legal.

The fact that nations are continually spending more than they take in cannot turn out well in the long run. The word "credit" comes from the Latin "credere," which means "to believe." The system will only function as long as lenders believe in borrowers. Once the belief in the creditworthiness of borrowers is destroyed, hardly anyone will be willing to buy their securities.

When that happens, the system is finished.

Grekland, Spanien och grunderna i macro

Rolf Englund blog 2010-05-29

Nästa gång Du möter en sån där som ojar sig över något lands dåliga statsfinanser så fråga honom om han, eller hon, anser att underskotten bör skäras ner.

Njaa, inte nu precis blir nog svaret, för var och en som inte heter Lucas, eller givit Lucas Nobelpriset, förstår att det vore jätte-jättedumt.

Det måste ske på sikt, brukar det heta.

Rolf Englund blog 2010-02-02

The banks are under massive pressure to raise their core Tier 1 capital ratios to 9pc by next June.

This requires a €2.5 trillion adjustment according to the BIS’s Global Stability Board.

Most of that is going to be done by slashing loan books – deleveraging in the jargon –

since they cannot raise fresh capital at a viable cost and don’t wish to be nationalised.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, December 21st, 2011

There are clear-cut things that you do if you’re in a liquidity trap.

A liquidity trap is simply defined as when the private sector is in a deleveraging mode, or a de-risking mode,

or an increasing savings mode — all of which you can also call deleveraging phenomena —

because of enduring negative animal spirits caused by legacy issues associated with bubbles.

Paul McCulley, at John Mauldin, 3 October 2011

Highly Recommended

In that scenario, the animal spirits of the private sector are not going to be revived by a reduction in interest rates because there is no demand.

It’s not the price of credit driving the deleveraging. It’s "I took on too much debt during the bubble. I have negative equity in my home. I don’t care what the price of credit is, I already have too much outstanding. I am paying down credit!"

That can be entirely rational for an individual household. It can be rational for an individual firm. It can be rational for an individual country.

However, in the aggregate, it begets the paradox of thrift. What is rational at the microlevel is irrational for the community, or at the macro level, and

I’m amazed that this is not assumed as a given description of what we’ve got going on right now.

The paradox of thrift and the liquidity trap are fellow travelers that are functionally intertwined.

Could it be that people are confused because of all the attention paid to the liquidity the Fed has pumped into the system via quantitative easing — even though most of that only flowed into the most speculative and unproductive pockets in Wall Street?

That could very well be the case. But that diversion of attention is unfortunate because it clouds people’s vision of the larger picture, which is pretty straightforward. It’s really textbook sort of stuff. My friend, [Nobel Laureate, Princeton Economics professor and New York Times columnist] Paul Krugman, has been writing a great deal about it recently. If the private sector is delevering and derisking and you’re caught in the paradox of thrift, the public sector is supposed to go in the exact opposite direction. The exact opposite direction.

You mean that cutting federal spending in a liquidity trap, like we’re in, is absolutely counterproductive?

Yes, it’s ludicrous and I don’t use that word too often. There’s a large range of opinions about most issues, and rightfully so. But if you are in a liquidity trap and you are advocating frontloaded austerity—

/Ludicrous

ludicrous (comparative more ludicrous, superlative most ludicrous)

Idiotic or unthinkable, often to the point of being funny.

Synonyms: (idiotic or unthinkable): laughable, ridiculous

http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/ludicrous/

The Tea Party is really talking about killing the economy —

Again, it’s absolutely ludicrous. And if we need an example, we can just look across the pond and see what’s going on in Euroland. Putting somebody who is suffering from anorexia on a diet doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.

I mean, the historical parallel that a lot of us point to would be 1931, when Andrew Mellon said, essentially, liquidate, liquidate, liquidate and assets will be transferred to moral hands, and we’ll live a more moral life.

That was in 1931. Then in 1937, when it looked like the economy might have been having "a decent" economic recovery, we decided to slap it in the face with monetary and fiscal policy tightening.

And it only took World War II to lift us out of that extension of the Depression.

Yes.

Why can't the economy grow? It's the debt, stupid.

Added up, household, business and government debt now amounts to some $36.5 trillion, a new nominal record.

And that figure excludes the government's unfunded liabilities for Medicare and Social Security.

Wall Street Journal, Rolfe Winkler, 17 Sept 2011

The Relationship Between Peak Oil and Peak Debt - Part 1 Gail Tverberg Tuesday, 12 July 201

The Economic Consequences of the PeakStephen Cecchetti and his team at BIS have written the definitive paper

Debt becomes poisonous once it reaches 80pc to 100pc of GDP for governments, 90pc of GDP for companies, and 85pc of GDP for households.

“The debt problems facing advanced economies are even worse than we thought.”

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, 31 August 2011

Done badly, it could wreck them

The process of deleveraging has barely begun

The Economist print July 7th 2011

The general view is now that in this, the next round of the Great Recession,

there is a high risk of things getting worse, with no effective instruments at governments’ disposal.

The first point is correct but the second is not quite right.

Throughout the crisis – and before it – Keynesian economists provided a coherent interpretation of events

Joseph Stiglitz, August 9, 2011

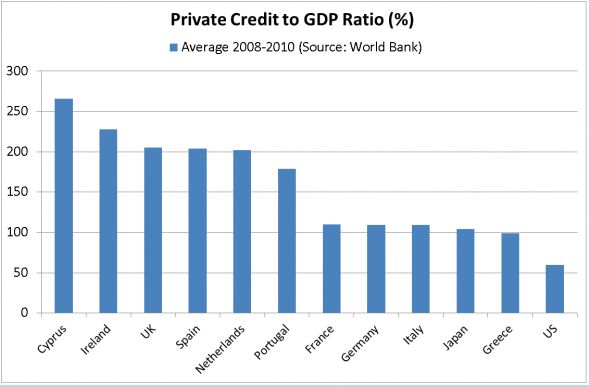

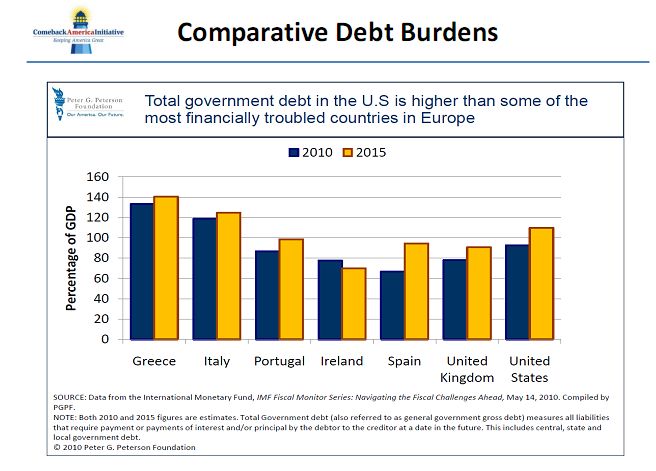

According to an index that Comeback America developed, the US is in worse shape from a fiscal standpoint than debt-plagued nations such as Italy or Spain

Comeback America is a conservative think tank funded mostly through a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, named for the founder the Blackstone Group private equity firm.

CNBC 23 May 2011

Kenneth Rogoff, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund and now a professor at Harvard University,

Given the low growth, he says, inflation above central banks’ targets could be helpful:

“A bit of inflation is by far the lesser evil compared with even lower growth.

Five per cent inflation for 2 to 3 years is not the end of the world. There are even some benefits.”

Financial Times 13 may 2011

UK is the most indebted advanced economy in the world

At every level – public, corporate, household and financial – the UK is attempting to pay off its debts.

As long as this continues, there's unlikely to be much growth in real terms.

Jeremy Warner, Daily Telegraph, 19 July 2011

As we now know, much of the above trend growth of the pre-crisis decade was the result of mounting leverage.

Now that the credit bubble has been removed, the natural rate of growth is bound to be quite a bit lower, whatever the situation in Europe and the rest of the outside world. Economies cannot both pay down debt and have fast growth. By the same token, if you don't pay down debt, you will be stuck in slow growth for years to come.

The adjustment is proving long and painful. Policy has so far concentrated on attempting to put off the moment of truth, to spread and smooth it. Yet events are conspiring to bring matters to a head.

What makes Britain particularly vulnerable to the sort of fiscal and financial market contagion now sweeping Europe is the magnitude of its banking sector, with liabilities several times the size of GDP. Taking all debt together - public, private, household and financial - the UK is the most indebted advanced economy in the world.

“Deleveraging” will dominate the rich world’s economies for years.

Done badly, it could wreck them

The process of deleveraging has barely begun

The Economist print July 7th 2011

Debt reduction, or deleveraging as it is known in the inelegant argot of economists, is a painful process. Growth suffers as consumers and firms, let alone governments, try to reduce their debts. Countries which experienced the biggest asset busts, such as America, Britain and Spain, have had the most disappointing recoveries. And the pain will continue: a careful look at the numbers suggests that the process of deleveraging has barely begun.

Debt can be reduced in several ways.

It can be paid off with the help of higher thrift

(though not everyone can spend less than they earn at the same time).

Its burden can be reduced through higher inflation or faster growth.

Or it can be defaulted on.

In practice, rich countries seem to be using different combinations of these approaches.

The question I have is this: does the BIS know that every sector cannot run financial surpluses at the same time?

Martin Wolf, Financial Times June 28, 2011

Vanliga medeklassmänniskor i Sverige har gjort mångmiljonaffärer på bostadsmarknaden med en belåning på 90 procent eller mer,

en nivå som skulle få vilken solbränd riskkapitalist som helst att skrika rätt ut av ångest.

Andreas Cervenka, svD Näringsliv 2 okt 2011

– I Sverige amorterar vi till exempel inte längre, lånen ses ofta som eviga, en status som bara staters lån hade tidigare. Förtroendet för återbetalningsförmågan har blivit extremt stort, det har skett på bara en generation, säger Daniel Waldenström, professor i nationalekonomi vid Uppsala universitet och forskare i ekonomisk historia.

Vårt finansiella system bygger på ömsesidig skuldsättning där nya värden skapas genom skuldsättning.

Få är idag helt utan skuld. I själva verket ser vi det som en självklarhet att

varje form av tillgång ska balanseras mot en viss grad av skuldsättning

Nils Fagerberg och Ulf Jakobsson, SvD Brännpunkt 24 aept 2011

Få är idag helt utan skuld. I själva verket ser vi det som en självklarhet att varje form av tillgång ska balanseras mot en viss grad av skuldsättning, det är så varje företagare upprättar sin balansräkning.

Skulden är numera ett självklart inslag i ekonomin. Den som är satt i skuld, är visserligen inte fri, men har i alla fall gjort en stor samhällsinsats genom att se till att nya pengar kommit i omlopp. Om det inte fanns några som var villiga att acceptera skuldbörda och räntebetalningar för att få tillgång till nytt kapital, skulle samhällsekonomin snabbt sluta fungera.

De svenska hushållen fortsätter att låna.

Under 2010 ökade lånen med 188 miljarder.

e24 24/3 2011

The trouble with this latest US recovery

it is built on monetary and fiscal policies which are wildly expansionary,

wholly unsustainable and will surely soon come to an end

Liam Halligan, Daily Telegraph 2 Apr 2011

During the final three months of 2010, while consumer credit fell by a net $20bn, this was more than offset by a $99bn rise in net corporate borrowing.

For Wall Street’s commission-based optimists, many of them with a mountain of stocks to sell, and their own home loans and credit card bills to service, such credit growth is Exhibit A when it comes to making the case that America is now out of the economic woods.

If only it were so. The trouble with this latest US recovery is that it amounts to little more than an economic “sugar-rush”. The recent growth-burst is built on monetary and fiscal policies which are wildly expansionary, wholly unsustainable and will surely soon come to an end. When the sugar-rush is over, and it won’t be long, the US will end up with a serious economic headache. Investors should keep that in mind.

Recessions are supposed to teach thrift. So when the amount Americans owe on their houses, cars and credit cards,

which more than doubled in the years between the tech and housing busts,

fell $550 billion in 2009, commentators said U.S. consumers had reformed.

But nearly 2½ years after the financial crisis, we still owe $6 trillion more than we did a decade ago.

Worse, figures released by the Federal Reserve in late February revealed that 65% of the recent drop in consumer debt stems not from our paying overdue bills but from write-offs--banks' foreclosing on homes, canceling credit cards and otherwise...

Time, March 14 2011

Why austerity alone risks a disaster

Martin Wolf, Financial Times June 28, 2011

A number of economies are in what the Jerome Levy Forecasting Center calls a “contained depression” – a period of sustained private sector deleveraging.

Implicitly, the BIS report rejects such a view. It argues for monetary and fiscal tightening across the globe.

“addressing overindebtedness, private as well as public, is the key to building a solid foundation for high, balanced real growth and a stable financial system. This means both driving up private savings and taking substantial action now to reduce deficits in the countries that were at the core of the crisis.”

The question I have is this: does the BIS know that every sector cannot run financial surpluses at the same time?

Repayment means spending less than one’s income. That is what is happening in the US private sector.

Households ran a financial deficit (an excess of spending over income) of 3.5 per cent of gross domestic product in the third quarter of 2005. This had shifted to a surplus of 3.3 per cent in the first quarter of 2011.

The business sector is also running a modest surplus.

Since the US has a current account deficit, the rest of the world is also, by definition, spending less than its income.

Who is taking the opposite side? The answer is: the government.

This is what a controlled depression means:

every sector, other than the government, is seeking to strengthen its balance sheet at the same time.

The BIS boldly calls for simultaneous private and public deleveraging. But what are to be the offsets?

That is the question.

The BIS provides no convincing answer.

Why economic recovery has been so long in coming

Some economists expected a rapid bounce-back once we were past the acute phase of the financial crisis

— what I think of as the oh-God-we’re-all-gonna-die period —

which lasted roughly from September 2008 to March 2009.

Paul Krugman, New York Times March 3, 2011

But that was never in the cards. The bubble economy of the Bush years left many Americans with too much debt; once the bubble burst, consumers were forced to cut back, and it was inevitably going to take them time to repair their finances.

And business investment was bound to be depressed, too. Why add to capacity when consumer demand is weak and you aren’t using the factories and office buildings you have?

Heretics welcome! Economics needs a new Reformation

He was one of the economists who knew there was big trouble brewing in the years leading up to the financial crisis of a decade ago but whose warnings were ignored.

Larry Elliott, the Guardian's economics editor and has been with the paper since 1988, 17 December 2017

According to the NBER, the “Great Recession” is now two years behind us,

but the recovery that normally follows a recession has not occurred.

While growth did rise for a while, it has been anaemic compared to the norm after a recession, and it is already trending down. Growth needs to exceed 3 per cent per annum to reduce unemployment—the rule of thumb known as Okun’s Law—and it needs to be substantially higher than this to make serious inroads into it. Instead, growth barely peeped its head above Okun’s level.

It is now below it again, and trending down.

Steve Keen June 11th, 2011

In Debunking Economics, Steve let the general public in on a little-known secret: that many widely believed economic models have been shown by economists to be wrong—hence the subtitle to his book, “the naked emperor of the social sciences”.

This is emphatically the case with the so-called “Efficient Markets Hypothesis”, which still dominates academic thinking about finance today—even after the Global Financial Crisis. Since 1995, Steve’s main research focus has been the development an alternative, empirically grounded theory, known as the “Financial Instability Hypothesis”, which argues that finance markets are inherently unstable. Steve’s forthcoming book on this topic, Finance and Economic Breakdown, will be published by Edward Elgar (UK) in 2012.

From November 2006 till March 2010, he published Debtwatch, a monthly report which explains the dangers of excessive private debt. In March 2007, he started the blog Steve Keen’s Debtwatch, which now has over 5,000 members and more than 50,000 unique readers each month.

Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis? (The Future of Capitalism), Amazon

10yrs after financial crisis, another crash is ‘almost inevitable,’ economist Steve Keen tells RT

Deleveraging, Deceleration and the Double Dip

For a long time I’ve focused on the contribution that the change in debt makes to aggregate demand,

in the relation that “aggregate demand equals the sum of GDP plus the change in debt”.

Posted on October 19, 2010 by Steve Keen

An obvious extension of that was that “change in aggregate demand equals change in GDP plus acceleration in the level of debt”—which would imply that change in unemployment is driven by changes in the rate of growth of debt.

Richard Thaler, winner of the 2017 Sveriges Riksbank prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel.

Thaler is a best-selling author and an entertaining speaker

Thaler has shown better than anyone that behavioural economics can be an engine of policy innovation.

Thaler has turned failure into success, helping economists thrive during a financial crisis that they had failed to avert.

The deleveraging process in the US and, to a lesser extent the UK, appears to have stalled

before it has even started to gather impetus.

John Plender, FT, February 8 2011

When central banks start tightening again, the potential for default in residential property is huge, especially in the UK and Spain where much mortgage lending is at floating rates.

Household sector debt in the UK and Spain amounted to 101 per cent and 85 per cent of GDP respectively in 2008. These inflated levels are unprecedented.

The best interpretation of our current difficulties is that we’re suffering from a deleveraging shock,

and that the economy will need support until over-leveraged players have had time to work down their debt.

Paul Krugman 9 december 2010

That logic implies that you need a tow, not a jump-start; the economy is going to need help for an extended period of time.

A. Gary Shilling: Will U.S. Avoid a Recession in 2012? April 2012

In a new book “The Age of Deleveraging: Investment Strategies for a Decade of Slow Growth and Deflation”*, Gary Shilling, an economist, argues for the deflationary outcome.

He expects American GDP growth to average only 2% over the next decade as the economy struggles to deal with the debt burden.

Buttonwood, The Economist print Jan 6, 2011

The baby boomers will be forced to increase their savings as they approach retirement, he argues.

In The Age of Deleveraging, Gary Shilling notes that with deleveraging comes slow economic growth,

and he details nine reasons why real GDP will rise only about 2% annually in the years ahead

— far below the 3.3% growth it takes just to keep the unemployment rate stable.

John Mauldin 15/11 2010

This new age of deleveraging was sired by the back-to-back collapses of the housing and financial bubbles in 2007 and 2008, both of which he had been forecasting since early in the 2000s. He begins his new book with a look at how both of those bubbles were created, how they grew and how he was lucky enough to have spotted them in their infancies. Gary loves to be among the few to spot them and predict their demises

Gary Shilling’s brand new book, The Age of Deleveraging: Investment strategies for a decade of slow growth and deflation.

A year ago, Dr. Gary Shilling published the influential book The Age of Deleveraging,

which followed his earlier work, Deflation (1998); and in today’s Outside the Box he updates us on his thinking

Of course, there is that slim, remote, inconsequential, trivial probability that our forecast of global deleveraging, of continuing global economic weakness and of recession is dead wrong,

and that all the government stimuli and other forces will revive economies enough to justify current investor enthusiasm. We doubt it, however.

via John Mauldin, 11 February 2013

The crisis has not proved a great turning point, so far.

The ratio of private gross debt to US gross domestic product rose from 123 per cent in 1981 to 293 per cent in 2009.

By the third quarter of last year, the ratio had fallen to 263 per cent.

Martin Wolf, February 1 2011

The crisis revealed the vulnerability of the eurozone to excessive accumulations of private and public sector leverage, caused by floods of surplus savings into bad investments via undercapitalised financial institutions.

Managing the deleveraging will be very hard, particularly without internal exchange rate flexibility.

This is regarded by most people as inconceivable. Yet back in, say, 1993 few expected Japan’s lengthy malaise either.

How the private sector deleveraging is to occur, without mishap, is far from clear. The chance of renewed economic weakness is large. So is that of financial shocks, perhaps in response to fiscal concerns.

Again, the mood about the eurozone is now more optimistic. But how the zone is to exit from its difficulties remains obscure.

European leaders have willed the end: survival of the eurozone. Whether and how they can will the means is still unknown.

Martin Wolf, February 1 2011

Martin Wolf about low interest rates and leverage

December 9 2010

The UK and a number of other economies, including the US, are both excessively leveraged and have weak financial sectors. The low interest rate policy is designed to prevent an uncontrolled collapse of this mountain of leverage into mass bankruptcy and, instead, allow debt to be paid down and the financial system to return to health more gradually.

Thus, we have to choose between low interest rates on current assets or better returns on what would soon be shrunken assets: with higher rates, house prices would fall further, unemployment would rise, more loans would default and banks would fall back into difficulties. Ms Altmann argues that the bubble economy was partly an illusion. So, then, must be a big part of the financial claims on which savers now depend.

“You can’t cut debt by borrowing.” How often have you read or heard this comment from “austerians” (a nice variant on “Austrians”),

who complain about the huge fiscal deficits that have followed the financial crisis?

The obvious response is: so what?

Martin Wolf, September 26, 2010

The problem is that, even after more than two years of near-zero official rates and huge amounts of stimulus spending, economies such as the US have failed to grow as strongly as hoped.

The hangover effect of the debt-fuelled house-buying and consumption binge that started to unravel three years ago.

People are no longer able to borrow unless they have a good credit history. In any event, many people do not want to borrow.

They are focused instead on reducing the debts they have taken on – a process called deleveraging – either by choice or because they cannot roll over debts with new loans.

FT October 31 2010

As the International Monetary Fund and World Bank meetings start in Washington,

the word “deleveraging” is haunting policymakers and investors.

It is now crystal clear to everybody that debt levels were absurdly high during the credit boom.

Gillian Tett, FT October 7 2010

What is not evident, however, is how much further that debt now needs to decline to produce any sense of normality.

We do not know, in other words, how far along we are into this “deleveraging” process, nor what this might mean for growth or asset prices.

Total liabilities of the shadow banks have dropped from almost $22,000bn two years ago, to nearer $17,000bn, or where it was five years ago.

The forces that will stop the imbalances are already very evident

Fiscal consolidation cannot properly occur in advanced economies until there is a strengthening in private demand.

For well rehearsed reasons, this is proving difficult to achieve.

The handover from fiscal stimulus to private demand growth isn’t happening as quickly as hoped.

Unfortunately, the private sector is still in a strongly deleveraging frame of mind.

Jeremy Warner, Daily Telegraph 7 Oct 2010

Deleveraging/The Chances of a Double Dip

The good life and rapid growth that started in the early 1980s was fueled by massive financial leveraging and excessive debt, first in the global financial sector, starting in the 1970s and in the early 1980s among U.S. consumers.

That leverage propelled the dot com stock bubble in the late 1990s and then the housing bubble.

But now those two sectors are being forced to delever and in the process are transferring their debts to governments and central banks.

Gary Shilling at John Mauldin 17/9 2010

The deleveragings of the global financial sector and U.S. consumer arena are substantial and ongoing. Household debt is down $374 billion since the second quarter of 2008. The credit card and other revolving components as well as the non-revolving piece that includes auto and student loans are both declining. Total business debt is down, as witnessed by falling commercial and industrial loans.

This deleveraging will probably take a decade or more - and that's the good news. The ground to cover is so great that if it were traversed in a year or two, major economies would experience depressions worse than in the 1930s. This deleveraging and other forces will result in slow economic growth and probably deflation for many years. And as Japan has shown, these are difficult conditions to offset with monetary and fiscal policies.

Meanwhile, federal debt has exploded from $5.8 trillion on Sept. 30, 2008 to $8.8 trillion in late August. Many worry about the inflationary implications of this surge, but the reality is that public debt has simply replaced private debt.

...

The Coming Collapse in Housing

Gary Shilling at John Mauldin 17/11 2006

The writer was chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush, and is dean of Columbia Business School.

He is co-author with Peter Navarro of ‘Seeds of Destruction: Why the Path to Economic Ruin Runs Through Washington,

and How to Reclaim American Prosperity’

Glenn Hubbard, September 13 2010

How did the pressures build before the blow-up? Imbalances in global saving coupled with investment growing for more than a decade led to low real interest rates around the world for many years, putting pressure on prices of assets and reducing risk premiums in financial markets

Bernanke’s recent Jackson Hole speech didn’t contain one reference to the key force driving the American economy right now:

private sector deleveraging

(here’s the previous year’s speech for comparison’s sake

By Steve Keen at John Mauldin 2010-09-06

Debt reduction is now the real story of the American economy, just as real story behind the apparent free lunch of the last two decades was rising debt.

The secret that has completely eluded Bernanke is that aggregate demand is the sum of GDP plus the change in debt.

So when debt is rising demand exceeds what it could be on the basis of earned incomes alone,

and when debt is falling the opposite happens.

I’ve been banging the drum on this for years now, but it’s a hard idea to communicate because it’s so alien to the way most economists (and many people) think. For a start, it involves a redefinition of aggregate demand. Most economists are conditioned to think of commodity markets and asset markets as two separate spheres, but my definition lumps them together: aggregate demand is the sum of expenditure on goods and services, PLUS the net amount of money spent buying assets (shares and property) on the secondary markets. This expenditure is financed by the sum of what we earn from productive activities (largely wages and profits) PLUS the change in our debt levels. So total demand in the economy is the sum of GDP plus the change in debt.

Lönepengar och lånepengarRolf Englund blog 2010-02-23

Households and companies will continue to reduce debt built up before the financial crisis,

according to a report by the Bank for International Settlements.

Bloomberg 6/9 2010

A study of 20 systemic banking crises that were preceded by surges in credit showed that in 17 cases, debt relative to gross domestic product returned to levels seen before the crisis, economists Garry Tang and Christian Upper wrote in the Basel, Switzerland-based BIS’s latest quarterly review.

“If history is any guide, we should expect to see a much more significant reduction in private-sector debt, particularly of households, than has so far taken place after the recent crisis,” they wrote. “Lower house prices may induce households to reduce their desired level of debt. Similarly, a lower level of output and tighter financial conditions could put firms under pressure to reduce their leverage.”

Paradoxes Of Deleveraging And Releveraging

From 1929 to 1933, everyone was trying to pay down debt — and the debt/GDP ratio skyrocketed thanks to contraction and deflation.

During and immediately after WWII, there was massive borrowing — but GDP grew faster than debt, and the debt burden ended up falling.

Paul Krugman, New York Times, September 3, 2010

When, however, the economy suffers from Post Bubble Disorder,

characterised by private sector deleveraging and a fat-tail risk of deflation

In such a liquidity trap, private sector demand for credit is, axiomatically, very inelastic to low interest rates,

as evidenced by contracting private sector debt footings, even when the central bank’s policy rate is pinned against zero.

In such circumstances, the central bank has a profound duty to act unconventionally

Paul McCulley August 2010

ballooning its balance sheet by monetising assets, either government or private, or both. Put differently, the central bank has a profound duty to meld itself with the fiscal authority, until the fat-tail risk of deflation is cut off (and then killed, in the famous words of General Colin Powell).

Indeed, this very idea is what gave Chairman Bernanke his nickname of Helicopter Ben back in November 2002, when discussing possible remedies to deflation in the United States were it to unfold.

Here’s what he said:

To generate increased growth in aggregate demand, some sector of the economy must be willing to proactively lever its balance sheet. And that must be the fiscal authority, if the private sector is intent on delevering.

Yes, I know all about the perils of long-term fiscal unsustainability. But I also know that in the long run, we are all dead. I see no reason to die young from fiscal-orthodoxy-imposed anorexia.

Full textAggregate consumer debt continued to decline in the second quarter,

continuing its trend of the previous six quarters.

As of June 30, 2010, total consumer indebtedness was $11.7 trillion,

a reduction of $812 billion (6.5%) from its peak level at the close of 2008Q3

Calculated Risk with nice chart 17/8 2010

Whatever you think about fractional reserve banking the truth is that we no longer have it.

Reserve requirements apply only to transaction accounts, which are components of M1, a narrowly defined measure of money. Deposits that are components of M2 and M3 (but not M1), such as savings accounts and time deposits, have no reserve requirements and therefore can expand without regard to reserve levels.

Washingtons blog 21/3 2010

With the repeal of Glass-Steagall, deposits have been used to speculate in every type of investment under the sun, using insane amounts of leverage. Instead of the traditional 10-to-1 ratio, the giant banks and hedge funds were using much higher levels of leverage.

For example, Congresswoman Kaptur told Bill Moyers that while - on paper - there are 10-to-1 reserve requirements, banks like JP Morgan were using 100 to 1 leverage. She said that, with derivatives, leverage might be much higher.

And remember that most of the credit in our economy is actually through the shadow banking system, not through traditional depository banking.

This U.S. debt to GDP started accelerating in the 1960s (with the Vietnam War, Space Race and continuation of the Cold War) when it took $1.53 to generate an additional $1 of GDP.

Then during the 1970s, with the continuation of the Vietnam War, it took $1.68 to generate $1 of GDP.

In the 1980s (including Leveraged Buyouts and Star Wars) it took $2.93.

In the 1990s (with the internet bubble) the debt it took to generate $1 of GDP climbed to $3.12.

However, the most incredible of all was the first decade of this century when it took over $6 to generate an additional $1 of GDP.

That decade included the war on terror, two wars, private equity firms (new name for leveraged buyouts) and housing and another stock market bubble, as well as promises of entitlements that we have no possibility of being able to keep.

Clearly, needing over $6 to generate $1 of GDP is unsustainable.

Comstock January 25, 2010

Eurozone credit contraction accelerates

Bank loans and the M3 money supply in the eurozone contracted at an accelerating pace in November, raising the risk that a lending squeeze will choke the region's fragile recovery next year.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, 30 Dec 2009

Banks have chosen to restrict lending as they struggle to meet tougher capital rules rather than dilute shares by raising fresh equity or accepting the onerous terms of state support schemes. This has prompted harsh criticism from finance ministers, but Professor Tim Congdon from International Monetary Research said the authorities themselves are to blame.

"This is becoming ridiculous. How can banks raise capital asset ratios and lend more at the same time? These people are barmy," he said, comparing the new rules with policy mistakes in the early 1930s.

Barmy

1. stupid, bizarre, foolish, silly, daft (informal), irresponsible, irrational, senseless, preposterous, impractical, idiotic, inane, fatuous, dumb-ass (slang) This policy is absolutely barmy.

2. insane, odd, crazy, stupid, silly, nuts (slang), loony (slang), nutty (slang), goofy (informal), idiotic, loopy (informal), crackpot (informal), out to lunch (informal), dippy, out of your mind, gonzo (slang), doolally (slang), off your trolley (slang), round the twist (Brit. slang), up the pole (informal), off your rocker (slang), wacko or whacko (informal), a sausage short of a fry-up (slang) He used to say I was barmy, and that really got to me.

insane reasonable, sensible, rational, all there (informal), sane, of sound mind, in your right mind

www.thefreedictionary.com

The Age of Deleveraging

Total consumer debt is shrinking for the first time on 60 years.

And the decline shows no sign of abating.

John Mauldin 19/12 2009

This recession was caused not by too much inventory but by too much credit and leverage in the system. And now we are in the process of deleveraging.

And this is true in Europe as well, and maybe more so; but today we will look at some data in the US.

Credit card companies have reduced available credit by $1.6 trillion dollars. And for good reason.

The coming debacle in commercial real estate loans is well-documented.

Past post-recession expansions have been built on growing credit and leverage. That will not be the case this time. We are going to see reduced lending and borrowing. Even though the federal government is running massive deficits, the stimulus portion of the debt will be running down in the latter half of 2010. There will be little political will to continue with massive stimulus and deficits.

While this is good in the long run, in the short run it will reduce GDP.

We know that the current driving force behind this downturn is “deleveraging”.

Overindebted households and undercapitalised banks are adjusting their balance sheets, building up savings in the first case and restricting lending in the latter.

There is no chance of a sustained economic recovery until that process is almost complete.

Wolfgang Münchau, Financial Times, December 28 2008

We are still some way from that point. For example, on my calculations it will take a total peak-to-trough decline in real US house prices of some 40-50 per cent to get back towards long-term price trends and for price-rent ratios to return to more sustainable levels. We are about half-way through this process.

I arrive at three policy priorities for 2009. The first is for central banks to avoid deflation.

If ever there has been a need for a central bank to target price stability, it is now.

I mean this in the European sense of the term, meaning a small but distinctly positive rate of inflation, say 2 or 3 per cent annually.

I worry, though, that the US will try to raise inflation afterwards, which would reduce the real level of US debt but create massive distortions in exchange rates and financial flows and produce another global financial and economic crisis.

The second priority is to shrink the financial sector. A disorderly collapse would be catastrophic, but it is neither desirable, nor possible, to maintain the financial sector at its current excessive size. Take the market for credit default swaps, an unregulated $50,000-$60,000bn casino that serves no economic purpose except to enrich its participants at massive risk to global financial stability.

We are living through the painful end of an age of leverage which saw total private and public debt in the US rise from about 155 per cent of gross domestic product in the early 1980s to something like 342 per cent by the middle of this year

Once, monetarism and Keynesianism were considered mutually exclusive economic theories. So severe is this crisis that governments all over the world are trying both simultaneously.

Niall Ferguson,Financial Times, December 18 2008

Every tumultuous period of financial boom and bust comes to be defined by a word or catchphrase.

Tulipmania. The Great Depression. The dotcom bubble.

The word that could define the financial times we are now living through — and the economic pain that has begun — is leverage.

Bill Powell, Time Magazine, October 23 2008

Leverage Is an 8 Letter Word

John Mauldin, Nov 21 2008

Leverage is an eight-letter word, which the markets now regard as twice as bad as the two four-letter words debt and pain (or fill in your own four-letter words).

As I have written for a very long time, there are two aspects to the current recession and financial crisis.

The first is the fallout from the subprime crisis, which has morphed into a full-blown credit crisis. That coupled with a housing crisis has sent the nation into what looks like it will be the worst recession since 1974.

The second phase to hit banks and lending institutions is the normal recession problem of increased losses on all sorts of loans. Credit cards, home equity loans, residential mortgages, and especially commercial property mortgages all suffer during a recession.

Every tumultuous period of financial boom and bust comes to be defined by a word or catchphrase.

Tulipmania. The Great Depression. The dotcom bubble.

The word that could define the financial times we are now living through — and the economic pain that has begun — is leverage.

Bill Powell, Time Magazine, October 23 2008

Leverage was the mother's milk of Wall Street — and of Main Street — for the past 20 years. Leverage meant debt, specifically the number of dollars you could borrow for every dollar of wealth you had.

On Wall Street, debt funded investments in pretty much everything a financial firm could bet on, including the toxic mortgage-backed securities that led the way into this crisis.

On Main Street, it meant borrowing to buy a house or a condo — maybe two — then perhaps borrowing again off the increasing value of that property to pay for something else: a flat-screen TV, a new set of golf clubs, your daughter's braces.

The debt binge was fueled by easy money and the belief that prices of assets — those of houses in particular — never went down; only interest rates did.

That era is over.

It will be replaced by what will be one of the more painful, and consequential, economic chapters in our history:

the great deleveraging of America.